By Tom Gann

New Socialist

October 16, 2021

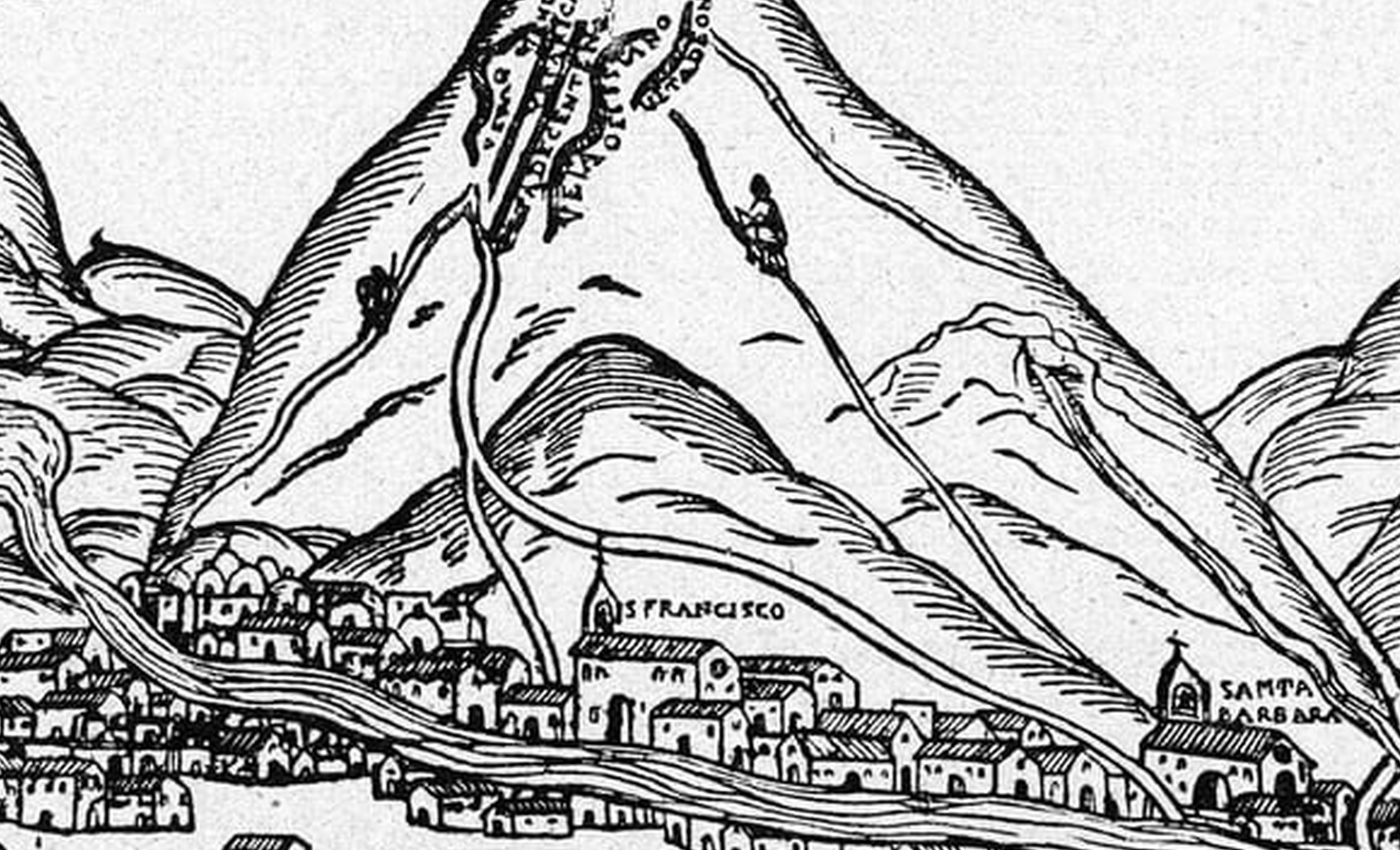

Image: Cerro de Potosí from Crónica del Perú, 1552, by Pedro Cieza de León

The Marxist geographer talks with Tom Gann and josie sparrow about world ecology, Marxist beef, and what it means to be in solidarity with oppressed and devalued natures.

Jason W. Moore’s work—from A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature and the Future of our Planet (co-written with Raj Patel), to the huge range of essays and interventions he makes freely available on his website to—perhaps above all—his book Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital—has been absolutely crucial in our understandings of ecological Marxism, and foundational for a great deal of what we wanted this edition to be. Jason’s work combines a rigorous, creative conceptual innovation, clarification, and (as Fanon knew to be a necessary, particularly when dealing with the imperialist context

) stretching of Marxist categories with a deep understanding of history and a commitment to rendering it concrete, along with a generosity and responsiveness to the world and its potentialities for change. We were very happy to be able to speak with Jason, and are sp grateful for the carefulness and generosity of his responses. This discussion took place over Zoom, and has been slightly edited for clarity, and to unfold certain points.

TGTo start off, and perhaps for readers of New Socialist who might not be terribly familiar with your work, what do you feel are the really specifically political implications of your work, if that’s not too broad a question?

JSThat’s a huge question.

JMIt’s a fantastic question. I think in the simplest possible terms, it’s about overcoming this false divide between jobs and environment, but that’s too simple. Really, it’s a challenge to what Marx criticises the German socialists for doing in ‘The Critique of the Gotha Programme’… Marx says, “you, the German socialists, have given labour this supernatural power, when in fact labour is not the only producer of wealth; it’s also the soil, the web of life”. And that sets up a quite fascinating political and ideological set of questions, because it’s true: if you look at post-1968 environmentalism, they have adopted their supernatural object, ‘Nature’, that must be saved, that must be protected, and which is separate from the socialist, or communist’s sacred object, which is ‘Labour’. That’s also separated from the second wave feminist sacred object of ‘Woman’, ‘Gender’, however you want to phrase that. We can look at many other social movements who have adopted similar kinds of sacred objects. So, the question becomes, not only how do we engage in an ideological struggle to de-fetishise those sacred objects, but: What are the common threads?

In a nutshell, my common thread is to look at the formation of the proletariat, around paid work, the femitariat, around socially necessary unpaid work, care work, etc., and the biotariat—the work of the web of life as a whole. That last one, the biotariat, is a term I’ve borrowed from the poet Stephen Collis.

Of course, these are overlapping and interpenetrating realities, and they constitute together what I would call the planetary proletariat. To some that might sound a bit woo-woo. But I think it actually foregrounds the struggle over the relations and conditions of work—of the work of humans, and of the rest of nature—in developing capitalism. So for me, the strategic common ground of planetary proletarian politics is to put together proletariat, femitariat, biotariat into a new practice (and praxis!), and pursue the interconnect abolition of the interconnected relations of proletariat, femitariat and biotariat. My common thread is to look at the formation of the proletariat, around paid work, the femitariat, around socially necessary unpaid work, care work, etc., and the biotariat—the work of the web of life as a whole.

TGThat’s really interesting, and it actually feeds in a bit to some of the other questions we were wondering about asking. Before we get into that—both josie and I are quite interested in how, in these major New Left Review interviews, they kick off with this rather pompously-phrased question: “what is your formation?” So we wanted to ask something similar. In Capitalism in the Web of Life, there’s a really generous acknowledgement of its collaborative character, but at the same time, there’s—and one might want to be cautious with ‘innovation’, but perhaps it’ll do for now—also this very precise conceptual innovation. So, the question about your formation is perhaps what got you to that conceptual innovation and clarification? What were the processes of forming the You that got you to writing that book?

JMBiographically or intellectually, or both?

JSBoth, I think.

JMBiographically, I grew up in the working class. I was raised by a single working mother, so I understood at some fundamental level what a feminist working class perspective looked like. I grew up in the really big heartland of post-68 environmentalist struggle in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Famously, in the 1980s and 1990s, there were struggles to protect what were called the Old Growth forests against logging interests. I was always dismayed at the environmentalist disdain for the working class, and even their opposition to efforts to put together an environmentalism of the working class—which we still don’t have. We have people like Joan Martinez Alier celebrating the environmentalism of the poor, but from a Malthusian perspective, even though he dresses it up. Most environmentalism is what Peter Dauvergne calls “the environmentalism of the rich.”

It’s the kind of environmentalism advocated by David Attenborough, Johan Rockström—I imagine you saw the interview… What arrogance from people like Rockström, who has spent his life sneering at working class politics and qualitative social science of any critical variety! Here’s someone who is the “chief scientist” for Conservation International, which announces on its website, proudly, its commitment to the financialization of nature. So, my formation – influenced by New Left heterodoxy – led me see these elements of feminism, working class politics, and environmentalism were all elements of a synthesis – and that none was, by itself, sufficient..

I had the benefit of working with the great Marxist thinker John Bellamy Foster at the University of Oregon in the early 1990s, and—despite all the thunder and fury he’s rained down upon me—a good chunk of the world-ecology synthesis is indebted to that conversation. Really, I see much of what I’m doing as a kind of dialectical synthesis of what he’s doing with other traditions of anti-imperialist Marxism, feminist socialism, anti-racist communism, etc. So, for me, that combination of biography and then working with John Bellamy Foster really fed a dialectical imagination.

It was with Bellamy Foster that I learned Richard Levin and Richard Lewontin on the Dialectical Biologist—and I still remember saying to Bellamy Foster in a seminar that this should our methodological text, and he sort of laughed it off and didn’t quite know what to do with that.

He still celebrates them, but does nothing like what that dialectical imagination does. A dialectical imagination works in the grey zone; it proceeds through variation and diversity, not in spite of these. A dialectical approach understands no individual, no “camp,” has all the answers. That’s why I call the world-ecology conversation a conversation – it’s open ended, experimental, willing to risk confounding mainstream – but also radical – orthodoxies. The Dialectical Biologist pointed me towards a relentlessly creative and connective historical materialism. I mean, Marxists and others cite Marx on the ruthless criticism of everything existing, but they don’t really practice it because there’s this kind of fear of what happens when we go beyond the received orthodoxy. But Marx himself was always going beyond the received orthodoxy, right?

I was, then, very lucky to have a very heterodox group of older, senior scholars who could help me from going off the rails, and really, in their own ways, encourage this idiosyncratic, connective, creative imaginary that, with Capitalism in the Web of Life and the world-ecology conversation, I’ve tried to encourage. The phrase that I use for that is ‘intellectual disobedience’. We need to practice intellectual disobedience against the orthodoxies, against the disciplines. We need to find and sustain the contradictory spaces within the global knowledge factory to open liberated zones where people can do connective, curious, insightful work independently of the disciplines, independently of the disciplining mechanisms of the knowledge factory. Those disciplining mechanisms include, and, by the way, many orthodox Marxists, who seem to be quite terrified of any dialectical reimagination of Marxism. They would surely have denounced Marx in 1876 for revisionism and going away from the true Marxist path. “You, Sir, are not a Marxist,” they would have said in response to the ‘Critique of the Gotha Programme’—in which, by the way, he not only criticises the German socialists for giving labour supernatural powers, but also points out that labour itself is a specifically harnessed natural force. Probably they would call him a monist. But we know Marx was not a monist, because the dialectical imagination always insists on differentiation within the unity. We need to practice intellectual disobedience against the disciplines. We need to find and sustain the contradictory spaces within the global knowledge factory to open liberated zones where people can do connective, curious, work.

What I’d share in terms of my formation is that, probably from some good decisions of mine and also some unwise decisions, I’ve found myself in spaces where I was not subject to the full force of the disciplining mechanisms of the university system, and yet managed to find a way. What I’ve tried to do with world-ecology is apply a heterodoxy: to say, this is not a theory, it’s not a line, it’s a web of conversations that look to connect power, profit, and life in long historical perspective, in the interests of developing a revolutionary and socialist praxis for planetary justice.

JSThat’s such a good answer. Let the record show that I’m just nodding along all the way through… that really speaks to me. I’ve never been able to find any place, either within the academy or Marxism, until I found New Socialist. Nobody gets, or got, what I’m doing… well, until I had a bit of Tom’s clout behind me, which says a whole bunch of other stuff.

JMPatriarchy dies a hard death, doesn’t it?

JSWell, yes, if it dies at all, would be my slightly pessimistic view.

JMWell, I have some thoughts on that… we can talk about climate crises and class crises and feminist historical materialism, because nobody looks at the history of these gendered class dynamics.

JS100%! It’s really interesting, I was just talking to somebody else earlier, who reminded me of this Andrea Dworkin quote: “I always forget I’m a woman, and then I go out into the world and misogyny reminds me”, and that feeling of constantly coming up against a limitation is quite similar to the condition of being proletarianised, as well. So you find yourself, as a working class woman, limited in all these various ways, and also if you want to do something that’s kind of… considered to be methodologically almost a bit ‘wacky’, or to have a method that reflects the politics of what you’re trying to do. In ‘Critique of the Gotha Programme’, Marx talks about how any hypothetical communist society would enter the world bearing the birthmarks of the old order, and quite a lot of Marxists seem to read that and say, “that’s fine, we don’t need to do anything about it now that we’ve recognised it’s the case; we still have to use the instruments of the old order, and somehow a critical awareness will be enough.” It’s the big question of revolutionary Marxism, isn’t it? To what extent are the old tools useful, if at all?

Maybe, connected to that, I’ll ask my Big Capitalism Question. You write, quite early on in Capitalism in the Web of Life, a really arresting line about what if we could understand our cars, and our breakfasts, and our jobs are world-historical activity.

This is obviously really important, and important for me, in terms of trying to think relationally, including about very minute relations.

It also strikes me, however, that there is a tension there between a sort of neoliberal personal choice discourse: ‘your breakfast is world-historical, so all you have to do is buy this eco-friendly breakfast cereal and you’re fixed,’ and the ‘no ethical consumption under capitalism, so fuck it’ line, which I’m really cynical about because it seems a disavowal of relationality and abandonment of any power or hope to change things, which troubles me.

What reminded me of this was there’s a bit in a Mark Fisher book where he uses the notion of interpassivity (I think it was Robert Pfaller who coined it) to talk about people outsourcing concern for the climate, concern for ecological things, concern for what we’d broadly define as the web of life. There’s this quote where he says, “as long as we believe in our hearts that capitalism is bad, we’re free to continue to participate in the capitalist exchange”

. So, there’s a real tension here: on the one hand, you’ve got the necessity of resisting, personal choice-ism, on the other hand the necessity of not developing this almost Protestant view that as long as the content of my soul is pure, so whatever I do is fine. So, how do we balance those things?

JMThere’s a lot going on in that question! It’s a fantastic question, josie. Let’s begin with one of the signal accomplishments of the mainstream environmentalism that emerged after 1968. Almost single-handedly, the new Environmentalism revived the theory of consumer sovereignty: the idea that capitalism is a plebiscite of dollars, that production choices respond to what people buy and don’t buy. This is of course at the heart of personal responsibility politics, which also enjoys an unsavory relation to Malthus’ arguments about “virtue” which echo across the discourse on “ethical consumption.” It’s instructive to remember that even liberal, left-liberal economists like John Kenneth Galbraith in the 1960s had destroyed the theory of consumer sovereignty. The most powerful critique came from Marxists like Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy, , because they lived in this moment of the full-blown maturation of what they called the “sales effort”.

The mid-Sixties were a time when this –this gigantic marketing apparatus with “modern advertising” in television and radio, had seemingly colonised everyone’s life. This of course maps very perfectly on today’s era of platform capitalism, the Facebook-isation of everything, in which the product is you—that is, the shaping of your desires, the sense of an alternative. Which of course feeds into the passivity question, because if consumer choice doesn’t make a difference, then fuck it, I’ll do whatever I want.

In contrast, the theory of producer sovereignty, which has long been held by Marxists, says in very powerful ways that the sales and marketing apparatus is fundamental to the expanded accumulation of capital. It is intimately connected with the shaping of consuming subjects, so it very much colonises our mentalités and determines in large degree what we see and don’t see. But, of course, if we’re good Marxists, we see the tendency met with the counter-tendency and the pushback. Today bourgeois individualism remains potent, but I see among younger activists, writers, and students a growing scepticism around consumer-oriented, personal responsibility politics. Even in the US, —and this is quite striking—for the first time since the 1930s or 1940s (and momentarily in the late 60s and early 70s) one can talk about class.

There is a growing sentiment that this consumer capitalist mindset that has been endorsed by environmentalism is entirely false—it’s not consumer capitalism, it’s the capitalism of the bourgeoisie that creates consuming desires through platform capitalism, social media, and the collection of all this data on our lives, the better to shape our desires on a daily basis. Sometimes this is called “data colonialism,” which is fine so long as we remember that imperialism is the bourgeoisie’s preferred mode of waging the class struggle. There’s a class struggle on the level of everyday life that has to be confronted head on. And, just to go back to what you were saying earlier, that’s a class struggle of everyday life, at the level of buying food, shopping for groceries, cooking food, buying clothes, and everything else. All of which is an irreducibly gendered class struggle. And so one of the problems of the orthodox left (and we see this in ecosocialism especially) is really the inability to deal with how the climate class divide fits together with climate patriarchy and climate apartheid. That’s crucial to link the politics of everyday life with the politics at the commanding heights of whatever civilisation we end up living in. There’s a class struggle on the level of everyday life. And that’s a class struggle at the level of shopping for groceries, cooking food, buying clothes, and everything else. All of which is an irreducibly gendered class struggle.

Gramsci in the Web of Life

TGYour work has this really valuable and productive way of being simultaneously very insistent on the role of the law of value (especially its gravitational role), while also emphasising the non-identity of the value form and value relations. So, there’s this in some ways quite tightly circumscribed idea of wage labour or commodification, opting for this almost austere idea, rather than for those parts of a Marxist or Marxian tradition that try to expand that, and then exploring the relationship between commodification and appropriation. I was wondering how much your work both engages with and can illuminate some of the contemporary Marxist discussions about the value form, on the one hand, but also some of the social reproduction and domestic labour debates, where I guess you have someone like [Lise] Vogel arguing for a restricted conception of value-creating labour, and someone like [Mariarosa] Dalla Costa arguing for an expansive one, wanting to put more stuff, more work, into the category of value creation.

I wondered how you felt your work engaged with these debates within Marxism, both around the value form and domestic labour.

JMIt’s an outstanding question. There’s so much going on so I might have to give one answer, and then come back and follow up with whatever I left out.

Usually, when Marxists utter the term “the law of value” or the “value form”, your eyes glaze over. Mine certainly did, for a very long time. You’re ready for this extremely turgid, schematic account of how the law of value works, and it’s often quite abstracted from the actually existing relations of production and reproduction, of webs of life, of the history of capital accumulation, and so forth. [Capitalism in the] Web of Life, then, was an attempt not to provide the answer, but to push the value discussion into a very different register.

From the start, the value discussion says there is a double register of the law of value, that I call the ‘law of cheap nature’. And that says, on the one hand there is an incessant drive to reduce the costs of production, especially what I call the Four Cheaps: labour power (including unpaid work), food, energy, and raw materials. This is a logic of capital moment. One other hand, there’s a Gramscian or ethico-political moment of devaluation, of devaluing the lives and labour of “women, nature, and colonies,”

to quote Maria Mies. So, in other words, valorisation and devaluation, in this scheme, form an organic, differentiated unity.

I point out that, for Marx, the dialectic of value and use-value in fact refers to a disproportionality, between “paid” and “unpaid” work. This connects to my earlier distinction of the Planetary Proletariat, premised on the uneven relations between wage-work and the unpaid work of the femitariat and biotariat. For Marx, value is valorised work – that is, set in motion to create more capital. It occurs within the cash nexus. But remember Marx’s critique for the German socialists? Soils and forests are also sources of wealth, they are use values. Now, use value should not be confused with utility, which is what happens a lot. Use value is, rather, the dialectical negation of value. In the Grundrisse, reckons it is as the antagonism between “economic equivalence” and “natural distinctness.” Use value refers not just to the useful properties of a tree or a blueberry bush, but also to the unpaid work of humans and the rest of nature. What I say in Capitalism in the Web of Life—and I’m trying to tease this out and elaborate this further in my new book—is that for every act of exploitation (of surplus value within the cash nexus, of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie), there is a disproportionately larger quantum of unpaid human and extra-human work. For Marx, the dialectic of value and use-value in fact refers to a disproportionality, between “paid” and “unpaid” work.

Now, at one level this is widely registered. We understand that, say, more and more steel attaches to less and less labour power, or more and more bushels of corn attach to less and less labour power—but when it comes to unpaid work there is an extraordinary refusal to see it.

And the final point I would add—this is where I’ve been very much inspired by the work of Claudia Von Werlhof, who unfortunately is almost entirely forgotten… she points out that Nature and Society are these ruling abstractions (think of Marx and Engels in the German Ideology), these ruling ideas, that are treated as real.

Ruling abstractions are operative guidelines of ruling class power. As von Werlhof and others have made clear, the ruling abstraction ‘woman’ developed through the category of Nature. And Nature, she says, is basically what the rulers say when they don’t want to pay for something. It’s one of my favourite essays, but again because of the patriarchal biases of readers (including me!), and of Marxism, I didn’t come across it until it was too late for Web of Life.

The point about real or ruling abstractions is impossible to overstate. Intriguingly, the most aggressive critiques of Web of Life completely excise the argument, essentially verifying my critique of their economic reductionism. There’s tremendous real world relevance at stake here. At the heart of the struggle for planetary justice is an ideological struggle around these ruling abstractions “Man” and “Woman”, or “Civilisation” and “Savagery”, or what we call today “Society” and “Nature”. These are not semantic quibbles. It’s not just ‘let’s find the right word’, it’s not an exercise in ‘Woke Marxism’—it’s an exercise in the critique of ideology, and these geocultural mechanisms of sexism and racism and Prometheanism (that is, the drive to dominate nature), are the ideological conditions for the superexploitation of the planetary proletariat. Geocultural domination is instrumental to sustaining and advancing the rate of profit. And we know this because capitalism gets rid of ruling abstractions that are not useful to advancing the rate of profit. We don’t need to become metaphysical about this, we need to take seriously historical materialism around it.

TGSomething else I think is really valuable about Capitalism in the Web of Life is, and it was interesting you mentioned this explicitly, is that there is this sort of hidden Gramscianism.

JMAbsolutely!

TGSo, I think there’s a lot of everyday discourse about ideology that treats ideology as largely about securing consent and legitimacy—and obviously that’s a role it has—but then I think your emphasis on ideology as doing more than that, as being present in production or reproduction, as productive (something Gramsci doesn’t ignore but a lot of Gramscians do) has always felt very valuable to me in how we might think more widely about ideology as something that is almost a productive force, including in terms of those devaluations which you’ve discussed.

JMThat means a lot. That was always my orientation, to put together these two moments: the law of value as a law of cheap nature, this moment of cost reduction, and then the moment of ethico-political valuation and devaluation, that’s fundamental. So as you say – probably more clearly than I – that cultural formations, not least those around Prometheanism, sexism, and racism, are productive forces, that’s crucial.

What I’ve come to realise is that much of the unfriendly reception to this argument has completely and totally ignored the critique of ideology and the question of real abstraction. It’s really a shame. There’s a debate that needs to occur. I’ve had many great teachers in my life who said more or less the same thing: what you want to do is to take the object of critique—that is the person or position you’re criticising—and take them at their strongest point. You don’t want to create these straw dog arguments. This is what’s happened with the non-critiques of Web of Life, which remove the question of real abstractions that is at the core of the book. From there it’s inevitable that one creates an undialectical object of critique. It’s effectively impossible to find an opportunity for generative dialogue out of such one-sided presentations.

In any event, this question of the critique of ideology is so fundamental, because it goes to this Nature/Society binary. I think what I was able to open up, if just a little bit, was to move this question of Nature/Society dualism from epistemology to ideology and therefore onto the terrain of world history. What I’ve tried to point out is that from the beginning—it’s obvious from the English language, but this happens with the Dutch and the Spanish too—from about 1550 you have the emergence of the modern sense of Society, the modern sense of Nature. Raymond Williams is great on this. Society and Nature emerge precisely in the century and a half after 1550. The timing is important because this was capitalism’s first great climate crisis. At this time, we see the emergence of this discourse amongst contemporaries of ‘Civilisation’ and ‘Savagery’. Of course – you know this living in Britain—this discourse was also an ideology, and it took shape out of the conquest of Ireland? The Irish were ‘Savages’. The expression “beyond the pale” comes out of this experience – the Oxford English dictionary says it doesn’t, but I’ve found a number of contemporary texts that use precisely this language. “The pale” referred to that old colonial line, a rough semi-circle around Dublin, inside of which were the “civilised” English, Anglo-Irish, settlers, and beyond which were the ‘savage and wild’ Irish—‘savage’ and ‘wild’ was the language of the time, just like many colonised people after that.

The language of civilisation and savagery, or what today is Society and Nature, drips with blood and dirt in the most palpable and direct ways possible. Indeed, capitalism has been shaped by recurrent and overlapping civilising projects, Christianising projects, and of course, after 1949, developmentalist projects in which everyone else is un-developed (just as earlier they were un-Christian, or un-civilised).

This kind of thinking – call it “Gramsci in the web of life” – leads to a fundamental political critique of mainstream Environmentalism. As we know, Environmentalism proceeds through a Man and Nature cosmology. One thing we can say is that the thinking that created the planetary crisis – Man and Nature and the Civilizing Project – will not be helpful to transcending that crisis. But I think we can go further. Man and Nature represents not on a practical philosophy of domination, but also a managerial philosophy. Conservationist thought, going back to the 16th century, of course pivoted on resource management. Colonial administration – colonial Peru is a great example, the place where the silver that built capitalism was mined – is another dimension of this. The goal in reclassifying Indigenous Andeans as naturales was basic to the labor mobilization and the geo-management strategy of turning colonial Peru into a gigantic extractive-export platform. Man and Nature represents not on a practical philosophy of domination, but also a managerial philosophy. Conservationist thought, going back to the 16th century, of course pivoted on resource management.

Some readers will know that I write a lot about “Cartesian dualism,” after the great philosopher Rene Descartes, writing in 1630s and ‘40s. As I’ve always insisted, Descartes’ thinking is important because it channeled the zeitgeist. He distinguished between “thinking things” and “extended things” as discrete essences, a move that readily leant itself to the ideological separation of Civilization and Nature that we’ve been discussing. What’s crucial here, however, is not the philosophical point so much as its managerial implications: what Harry Braverman famously called the “separation of conception from execution.” In sum, the managers reorganized production so that “thinking” work is concentrated in the minds of the bosses, and “extended” work is concentrated in the hands of the workers. This was part of a wider systemic movement to restructure production as a series of interchangeable parts – a restructuring that was, as I’ve demonstrated, evident in sugar plantations and shipbuilding centers at the time when Descartes was writing. In other words, the “scientific management” revolution associated with Frederick Winslow Taylor and twentieth-century Fordism was in motion centuries earlier. Now – bear with me! – fast forward to the 1960s, when “systems dynamics” matured. The systems models that led to 1972’s The Limits to Growth were developed at MIT’s Sloane School of Management – in case you’re wondering, the “Sloane” in question was the pioneering CEO of General Motors. Today’s “earth system” models trace their lineage to a management school: whether they are conscious of it or not, they are socialized to pursue “good science” that is soaked through the common sense of the manager. Another name for earth-system science might be Biospheric Taylorism, whose Prometheanism, like capital accumulation, knows no internal limits. Much of today’s Environmentalism – not environmental justice movements, which are very different – embraces the philosophy of planetary management premised, in the final analysis, on Man and Nature, the reified expressions of Bourgeois and Proletarian. Centuries later, we are too often captive to the Cartesian imaginary: of “thinking things” (the planners, the scientists, the bosses) and everyone else, ‘extended things’. This sensibility unifies the history of environmentalist thought from Descartes to Malthus all the way to ‘Limits of Growth’ and today’s Popular Anthropocene.

JSI think one of the reasons why this framework has always appealed me is that I’m third generation Irish. My entire family is from different strands of people who ran into each other in Liverpool as refugees from the Great Hunger, so all my grandparents were born in slums by the docks. We’re very recently ‘English’ and this was something I was aware of growing up—and then there’s a weird situation of how the city of Liverpool relates to England as often only provisionally English; there’s a version of ‘savages and civilisation’ discourse that goes on. So, to have an understanding of why I’m here—which is the first moment of doing philosophy: what’s happening here, why do I find myself here, in this particular situation?—I can only understand that through British colonialism, really poor colonial management, and then being the reserve army of labour, being part of a subaltern proletariat in a place that already had a proletariat that was undergoing some quite horrific things. So, I think it’s fascinating to me that anyone could disagree with this sort of framework, because it makes so much to me, working outwards from my own experience and understanding.

You mentioned earlier some of Bellamy Foster’s response to your work—interestingly, the Wikipedia page for ‘metabolic rift’ is almost entirely dedicated to the beef between you two! Now that’s what I call World Historical. But anyway… it always interests me to see the upper echelons of the academy rejecting a lot of your framework or analysis in this very strong way that doesn’t make a lot of sense to me. And, I guess one way of understanding it to me, albeit a vulgar Marxist way, is people trying to protect their own class interests. But why do you think you attract such opprobrium?

JMWhen you go after the sacred objects and call for a de-fetishisation, that then calls for a different kind of intellectual and therefore political practice. People have personal investments in a scheme of argument or a structure of specialisation. I don’t say that to belittle: they’ve invested their professional and often personal identities into a given specialisation. It’s the product of work, and that that has to be respected. At the same time—and what I’m seeing is a very interesting and encouraging generational divide—many younger scholars are much more open to arguments that transcend the tyranny of academic specialization and discipline.

I’m also the kind of person who is more interested in being interesting than correct… I’m never concerned if people want to take one element and leave the rest. That’s as it should be. In fact, that’s how I open Capitalism in the Web of Life. People should be constantly appropriating, making it their own, pushing it back out—and a lot of times, I’m really grateful! The result is that I see things I didn’t see at first, I’m excited to rethink and renew some of the key elements of what I’m thinking, and to extend it and broaden it. And, for those who have been paying attention to my work, you’ll have noticed that, for example, in this move into climate history, seeing the climate crisis as the result of this trinity of climate apartheid, climate class divide, climate patriarchy was implicit earlier – but now assumes much greater salience. For me, there a constant questioning of previous formulations as I encounter my blind spots. We all have them, and at its best, our political and intellectual communities help us to see something new, and support us to integrate those new vistas. The challenge, from a dialectical point of view, is that integrating new connections requires us to rebuild the intellectual house – it’s not a matter of adding on a new bedroom. Dialectically, the incorporation of new ideas and relations entails a rethinking of the whole.

That of course runs directly counter to an academic world that encourages people to engage in a kind of premature closure of whatever they’re studying. A previous generation’s “expertise” may or may not be relevant; but the academic world often insists upon it. Expertise tends towards the study of… ‘fetishised objects’ might be too strong, but the unnecessary and premature bounding of arguments. A great example of this would be somebody like Andreas Malm, who has written a very useful and sophisticated account of class struggles in English mill towns in the transition from water mills to steam power during the early nineteenth century. That strikes me as entirely relevant, useful, and generative in all kinds of ways. But don’t tell me that the heart of the industrial revolution was the steam engine. Please! I’m not even going to Marx for a defence on this, but not even Marx, if you’re going to be orthodox on this, believes this. It was only the fall in the price of cotton, he says, that allowed for the advent of large-scale industry. Now, what was it that drove the fall in the price of cotton? It was the ‘second slavery’—the revival of slavery, the reinvention of slavery—across the Americas but especially in the American South; the invention of the cotton gin; the dispossession of Indigenous peoples; the appropriation of a strain of cotton, hirsutum cotton, that had been developed by Indigenous people and could withstand the machine milling of Manchester textile mills; then the pushing of the cotton commodity frontier into the American South; and all through it, the audacious expansion of the plantation proletariat. So, please don’t tell me that the story of the English Industrial Revolution starts in England, either geographically or historically! At the same time, I don’t think any of this disqualifies and undermines Malm’s significant contributions, and I have said this many times. Please don’t tell me that the story of the English Industrial Revolution starts in England, either geographically or historically.

And so what I’m trying to do is to say, there are many more opportunities in the radical left—anarchist, socialist, communist—for intellectual synthesis that could be really useful. I don’t need to accept everything that, say, someone like Malm says about fossil capital to say there are extraordinarily useful elements of that contribution. The alternative I would suggest is an ethics of synthesis, one that draws on the spirit of engaged pluralism, through which our default intellectual procedure is both/and rather than the Cartesian logic of either/or.