By Joachim Boaz

Science Fiction Ruminations

November 21st, 2021

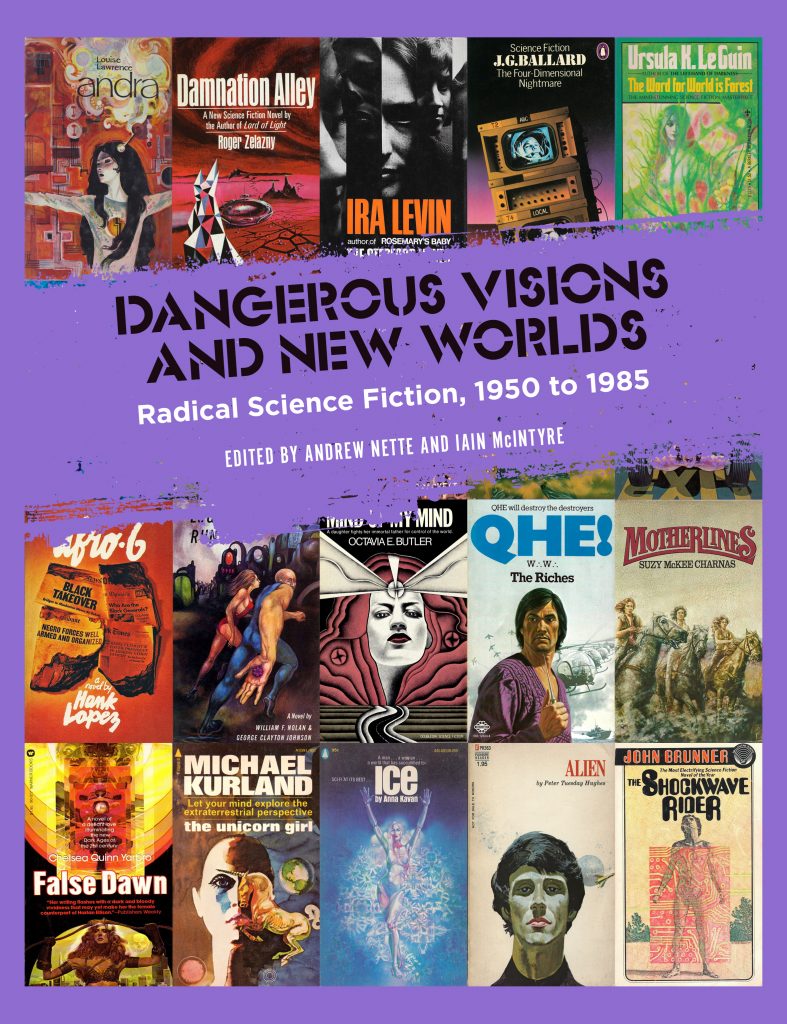

I’ve recently conducted a binge read of my ARC of Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction, 1950-1985, ed. Andrew Nette and Iain McIntyre (2021). It is a must buy for any SF fan of the era interested in exploring the larger world behind the texts. Considering the focus of my website and most of my reading adventures over the last decade, I can unabashedly proclaim myself a fan of the New Wave SF movement–and this edited volume is the perfect compliment to my collection and interests.

The editors and PM Press have graciously provided me with the introduction to the volume. Perhaps it’ll convince you to purchase your own copy!

Dangerous Visions and New Worlds

An Introduction

The “long sixties,” an era which began in the late 1950s and extended into the 1970s, has become shorthand for a period of trenchant social change, most explicitly demonstrated through a host of liberatory and resistance movements focused on class, racial, gender, sexual, and other inequalities. These were as much about cultural expression and social recognition as economic redistribution and formal politics. While the degree to which often youthful insurgents achieved their goals varied greatly, the global challenge they presented was a major shock to the status quo.

Science fiction, with its basis in speculation, possibilities, and the future, became the ideal vessel for expression in an era in which the focus of many was on the questioning and refusal of established power and social relations, on the one hand, and the exhortation and exploration of radical scenarios, on the other. The genre intrinsically reflected upon both lived and alternative realities—past, present, and future. A “New Wave” of writers who captured the utopian and dystopian zeitgeist leapt to prominence in the 1960s, coming to largely dominate the field by the 1970s.

Resistance to change came from authors, fans, and editors, often dubbed the “Old Guard,” who were wedded to the conventions of the so-called “Golden Age” of science fiction. This was the period, generally recognized to stretch from 1938 to the late 1940s, when the genre first began to attract major public attention. Despite some important exceptions, key examples of which can be found in this book, the strictures and censorship of long-running science fiction magazines, such as well-known conservative John Campbell’s Astounding, dominated the field during the high sales period of the 1950s and continued on into the 1960s. A focus on scientific progressivism, prim sexual morality, and linear narratives resulted in tales focused upon technological breakthroughs and space-conquering male heroes.

In their place came a flood of new work that challenged and destabilized the conservative norms of narrative and expression, as well as outlook and belief. Chafing at the way in which past conventions continued to weigh upon the present, some authors sought to distance themselves altogether by defining their innovative work as “speculative” rather than “science” fiction. This shift in focus was as much aesthetic as political. Influenced by modernist prose and poetry, William S. Burroughs and the Beats, New Journalism, psychedelics, and the quest for consciousness expansion, modes of expression became more disjointed and experimental and topics shifted to the state of inner rather than outer space. The New Wave still had its astronauts and interstellar explorers, but now they could be found psychologically crumbling under the physical and mental pressure of space flight and the directives of the oppressive military bureaucratic apparatus behind it. Elsewhere, the brave heroes of the past gave way to a new range of characters: genocidal antiheroes, cynical or conflicted over their role in imperial power games and corporate domination; overworked (or underworked) drones strung out on psychotropic or other mind-altering substances; those left in a deep state of confusion by the all-encompassing spectacle of modern mass media culture or made paranoid by pervasive political and corporate surveillance; and individuals left in despair at the commodification and destruction of the natural world.

The internal and external revolt expressed in the genre was in part facilitated by changes in the publishing industry. As we have detailed in our previous two works, Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950 to 1980 and Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture, 1950 to 1980, the postwar period saw the paperback displace the pulp magazine and, even with the increasing presence of television, novels were hugely popular. This allowed a growing number of authors to make it into print, including some of those previously excluded from mainstream publishing, such as people of color and LGBTIQ writers.

Ron walotsky’s cover for for the 1970 edition of England Swings SF, ed. Judith Merril (1968)

Ron walotsky’s cover for for the 1970 edition of England Swings SF, ed. Judith Merril (1968)

In terms of science fiction, Michael Moorcock’s rise to the editorship of the long running New Worlds magazine in 1964, the increasing popularity of genre novels, and the publication of groundbreaking anthologies such as Dangerous Visions and England Swings, all provided writers with new opportunities. Alongside the inclusion of radical commentary, experimental poetry, and other forms of expression previously foreign to SF magazines, New Worlds provided primarily British and American writers with the freedom to produce groundbreaking work. One of its admirers, the established yet highly controversial Harlan Ellison, subsequently helped to emphatically mark the New Wave’s arrival with the aforementioned hefty and influential 1967 anthology Dangerous Visions and to further underscore its importance with 1972’s Again, Dangerous Visions. Lauded by the critics and commercially successful, the two books included seventy-nine stories, five of which won major awards, and featured almost all of the key writers of the period, as well as detailed headnotes from Ellison regarding their work. The significant role that both Dangerous Visions and New Worlds played is acknowledged and honored by the title of the collection you are reading.

The rise of the New Wave was controversial. Because of the entrenched role of fandom and critique in SF, issues regarding form and substance were debated to a much larger degree than in other literary genres. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, these arguments raged in the pages of fanzines and magazines, in letters between authors and readers, and at conferences, forums, and social events. The split between Golden Age right-wingers and New Wave left-wingers was exemplified by the pro– and anti–Vietnam War advertisements, replete with lists of endorsees, taken out in the June 1968 edition of Galaxy Science Fiction magazine, a pivotal moment in the genre covered in this volume. While some experimental authors leaned to the right and some conventional ones to the left, for the most part, those whose work was skeptical, if not an outright rejection, of the political status quo were also more likely to question the nature of reality more broadly and engage in nonconformist prose.

In keeping with the New Left in general, few, if any, of the New Wave writers looked to the Soviet Union for answers, except where it emerged in the form of Eastern Bloc dissidence, such as in the work of writers like Stanisław Lem and Arkady and Boris Strugatsky. Although some Western revolutionaries turned to Maoist China, Guevarist Cuba, and new and/or refreshed variants of Trotskyism, state socialism appears to have had little appeal to the majority of science fiction authors who believed in a radical restructuring of society. Although some took part in public demonstrations and other overt organized political action, most opted to undertake activism and sedition via literary expression. In keeping with the antiauthoritarianism of the counterculture, visions for real-world reform and revolution were either relatively fuzzy or aligned most strongly with anarchism and radical forms of feminism.

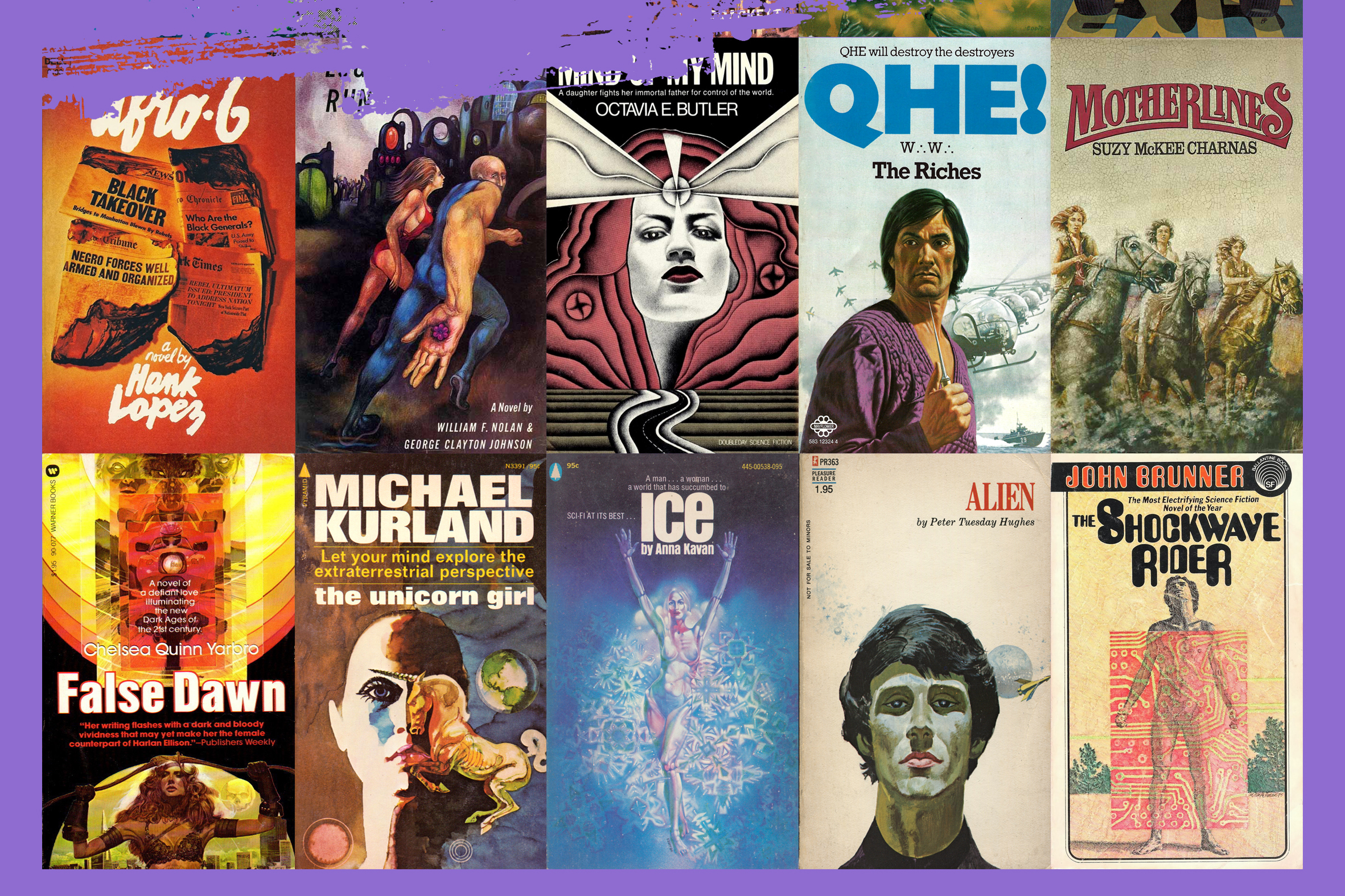

Not all of the writers covered in this collection believed that such widespread change was desirable or feasible. Some iconoclastic creative types, like Philip K. Dick, refused to align with any ideology or literary movement. Nevertheless, almost all were focused on shaking things up and testing the limits of morality and critical tolerance within and beyond the genre. The promise of science fiction, in its ability to transcend and travel beyond the limits of the present, was met not only by authors but also illustrators and designers. The influence of psychedelia, surrealism, and experimentation in general on book cover art during the period can arguably be seen most strongly in the science fiction field.

Literature always reflects the values, experiences, hopes, and fantasies of its creators, as well as the society and groupings they are a part of. Within speculative and science fiction genres the boundaries expanded rapidly to include pansexuality, communal lifestyles, hallucinogens, and radical politics. Changing, indeed, often reversing, conceptions of heroes and evildoers, and a blurring, if not complete demolition of the binary between them, were a regular feature of stories regarding near and far-future revolution and utopian societies. Alongside this came a renewed focus on dystopia. Living under the shadow of the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the escalating Cold War superpower nuclear standoff, which had come close to global conflict with the US/Cuban missile crisis of 1962, and ever more cognizant of ecological and other issues, writers such as Brian Aldiss, Chelsea Quinn Yarbro, Kate Wilhelm, and John Brunner produced disturbing apocalyptic works that reflected upon existing threats and warned of far worse to come.

KR’s cover for the 1968 UK edition of Brian W. Aldiss’ Greybeard (1964)

KR’s cover for the 1968 UK edition of Brian W. Aldiss’ Greybeard (1964)

For some, the end of the world was less terrifying than the continuance of it. The anomie, ennui, and spectacle of technologically drenched modern life was harshly depicted in many 1960s and 1970s works by J.G. Ballard, Barry Malzberg, Norman Spinrad, Thomas M. Disch, and others. Such visions often reflected the end of various dreams of the long sixties, in terms of a better, more fulfilling world to come, be it via a dazzling array of new consumer goods or communal revolution. As the 1970s progressed, the postwar economic boom faltered, and achieving social change, where it had not been reversed or fought to a standstill, became an ever harder and less glamorous slog. The cynicism and weariness that this engendered, as well as the impact of events such as Watergate on those who clung to faith in democratic institutions, became ever more extant in science fiction.

Uncredited cover for the 1973 edition of Norman Spinrad’s Bug Jack Barron (1969)

Uncredited cover for the 1973 edition of Norman Spinrad’s Bug Jack Barron (1969)

Despite setbacks and a growing backlash from the privileged, the 1970s remained a period of social challenge and change. Just as women’s liberation had pushed back against misogyny and the continuing second-class status of women within the New Left and counterculture, so it did within science fiction, with authors such as Ursula K. Le Guin, Joanna Russ, and Marge Piercy challenging the Old Guard and New Wave alike with their fiction and commentary. While science fiction emerging from and catering to the burgeoning feminist and gay and lesbian movements of the period often focused upon and channeled the inequities of the present into utopian and dystopian visions, writers such as Judith Merril and Alice Sheldon, writing under the moniker James Tiptree Jr., offered implicit critique through settings that involved a future in which liberation and equality were a long accepted and unremarkable fact.

Racism and allied issues, such as anti-colonialism, structural poverty, and changing patterns of immigration—as well as declining imperial power, in the case of the UK, and imperial overreach, in the case of the US—were regularly explored by radical SF authors during the 1960s and 1970s. Relatively few works by people of color were published, however, until the 1980s. Beyond towering contributions from Octavia Butler and Samuel Delany, the impact of science fiction was arguably felt more among a select range of African American musicians, such as Sun Ra and Parliament/Funkadelic, rather than authors. Although a number of near-future insurrectionist novels from black authors, including Samuel Greenlee and the little-known Joseph Denis Jackson, were published, they were generally marketed as thrillers rather than sci-fi. New Worlds and Dangerous Visions details, celebrates, and evaluates many aspects of this influential period of speculative fiction through twenty-four chapters written by contemporary authors and critics. New angles on key novels and authors are presented alongside excavations of topics, works, and writers who have been largely forgotten or undeservedly ignored. Interspersed between these chapters are short essays and cover spreads that serve to highlight the diversity of the field, as well as innovation in book cover illustration. With the exception of the Soviet Union’s Strugatsky brothers, whose work appears here to demonstrate how radicals were pushing the aesthetic and political limits in a very different context—and whose books were published to considerable acclaim in the West—the authors and books covered in this collection are primarily those published in the US and UK or by writers based in those two nations. This is partially for reasons of space, but also because these two countries’ milieus and book industries dominated the SF field in the period under review.

As with most movements proposing radical transformation, partisans of the New Wave sometimes portrayed the field as a decisive break with the literary and political conventions of the past. Such a focus on what was new tended to erase the work of those who had been advocating for change and practicing it in their work for some time. The legacy of George Orwell, Aldous Huxley, H.G. Wells, and other writers, as well as pioneering utopian and dystopian writers in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, was in many ways carried forward in the 1960s and 1970s. Although such early work falls largely outside the purview of this collection, the influence and continuing role of progressive authors who had an impact during the conservative 1950s, including Judith Merril, John Christopher, Mordecai Roshwald, Leigh Brackett, and John Wyndham, is scrutinized and given its due.

The impact of New Wave science fiction has, in turn, extended long beyond its heyday of the 1960s and 1970s. Although an explicit and heavy focus on technology returned with cyberpunk in the 1980s, the literary, thematic, and stylistic challenges and innovations presented in the preceding period were largely absorbed and refined rather than removed and rejected. While broader society has significantly changed and moral attitudes shifted, many of the social issues addressed by New Wave authors either remain or have been intensified, giving this body of work a continuing relevance.

Iain McIntyre and Andrew Nette