Netflix’s Maid and three recent best-sellers depict the agonies and rage of being a low-wage housekeeper or nanny. But all fail to identify capitalism itself as the culprit.

By Sophie Lewis

Boston Review

October 28th, 2021

Image: “housekeeper vacuuming a living room in a home” by franchiseopportunitiesphotos is licensed with CC BY-SA 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

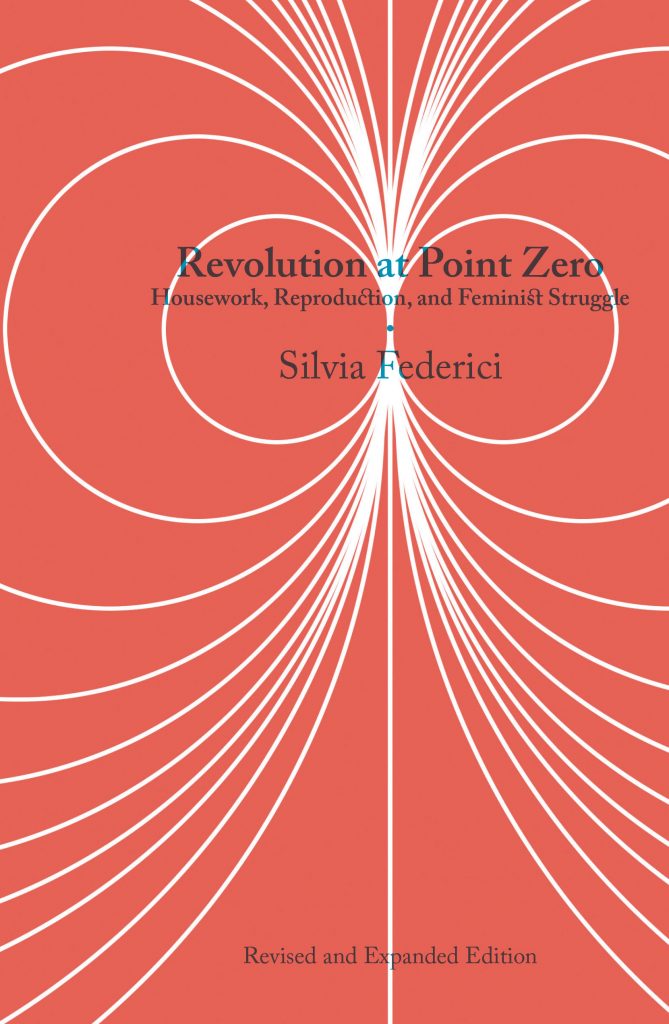

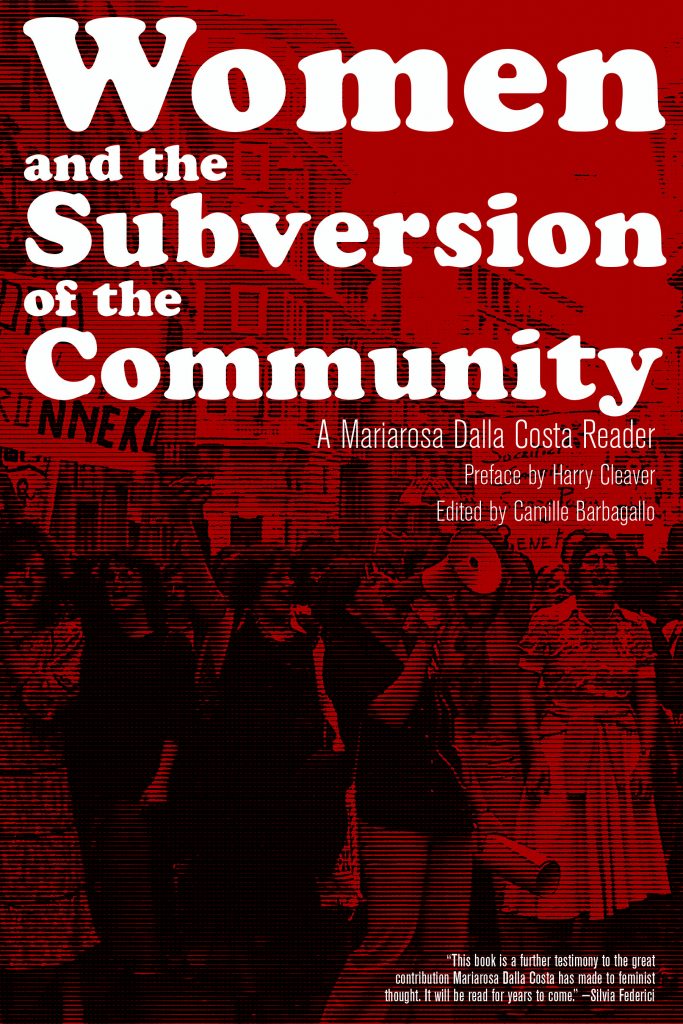

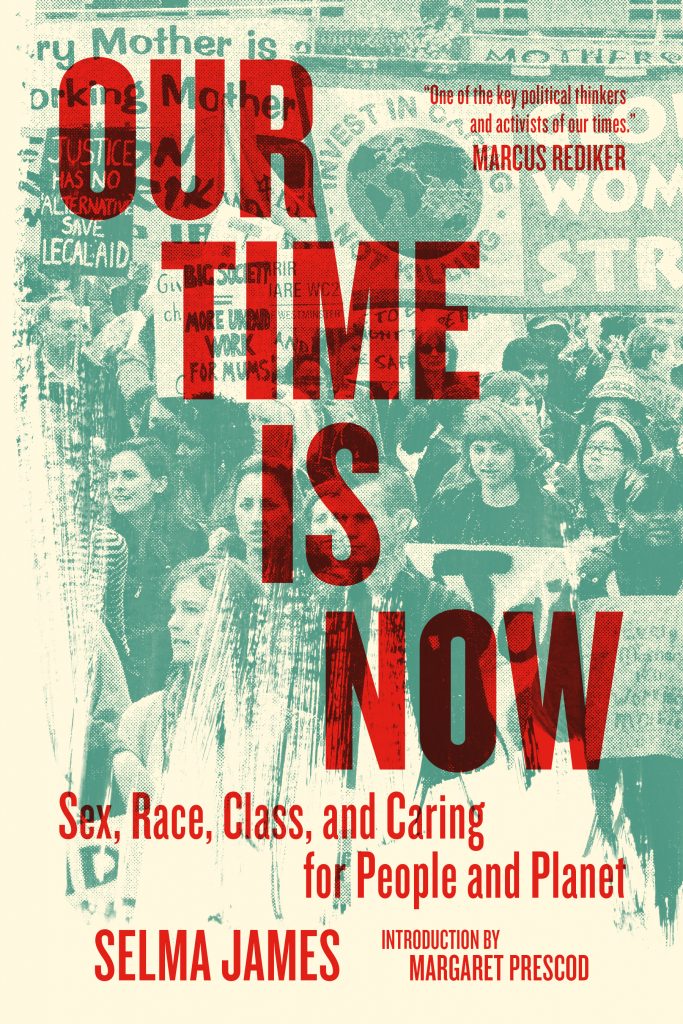

In the 1970s, a group of feminists collaborating under the banner Wages for Housework (including Selma James, Silvia Federici, and Mariarosa Dalla Costa) came up with a remarkably precise dictum to convey their perspective on the domestic labor performed by so many women in their own homes: “They say it is love. We say it is unwaged work.” Pointedly, they did not deny that unwaged housework might be a manifestation of love. Rather, Wages for Housework argued that “nothing so effectively stifles our lives as the transformation into work of the activities and relations that satisfy our desires.” In other words, the fact that caring for a household under capitalism often is an expression of loving desire, while at the same time being life-choking work, is precisely the problem.

The fact that caring for a household under capitalism often is an expression of loving desire, while at the same time being life-choking work, is precisely the problem.

That the “they” of the dictum—bosses, husbands, dads—are actually not wrong about this illustrates the insidiousness of the violence women encounter (and mete out) in the domestic realm. It’s the reason paid and unpaid domestic workers, and paid and unpaid mothers, still have to fight just to be seen as workers. And why being recognized as workers remains only a precursor to—one day—ending their exploitation and, by extension, beginning to know a new and different form of love.

Under capitalism, Wages for Housework perceived, “love” often serves the interests of the ruling class because it can be leveraged to depress wages (surely you’re not in this for the money) or even withhold them altogether (do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life). The gendered injunction to care “for love, not money” obscures the grinding, repetitive, invisible, energy-sapping, confining aspects of the work involved in making homes of any kind. The principle that some things “should not be for sale” becomes a way to disguise the reality that, everywhere, on every street, they are—and to excuse underpaying those doing the “selling.”

Thus the Wages for Housework movement, which was internationalist but had particularly strong ties to New York and Italy, was not for housework at all. On the contrary: these feminists were against it, against wages, and against all capitalist work for that matter. Their platform—which was rephrased and clarified by Federici in the formula “wages against housework”—was in this sense far removed from the now-ascendant demand that we “value” care work and grant “dignity” to domestic labor.

Wages for Housework contended that domestic labor under capitalism was intrinsically incompatible with “dignity.” Therefore no set of incremental improvements would ever get at the heart of the problem, namely that women will always be pressed into this work because capitalism needs them to perform the cooking, laundering, sheltering, and foot-rubbing that make it possible for workers to keep slogging away, day after day, generating surplus value. Rather than calling this involuntary labor “love,” Marxist feminists identified it as social reproduction, and Wages for Housework refused the notion that the family, any more than the factory, is “natural.” By contrast, today’s prevalent perspective, as expressed by the National Domestic Workers Alliance, seeks to ameliorate conditions such that the private nuclear household, with its army of paid and unpaid workers, might survive and hence continue to generate (“dignified”) jobs.