By Dick Flacks

Socialism and Democracy

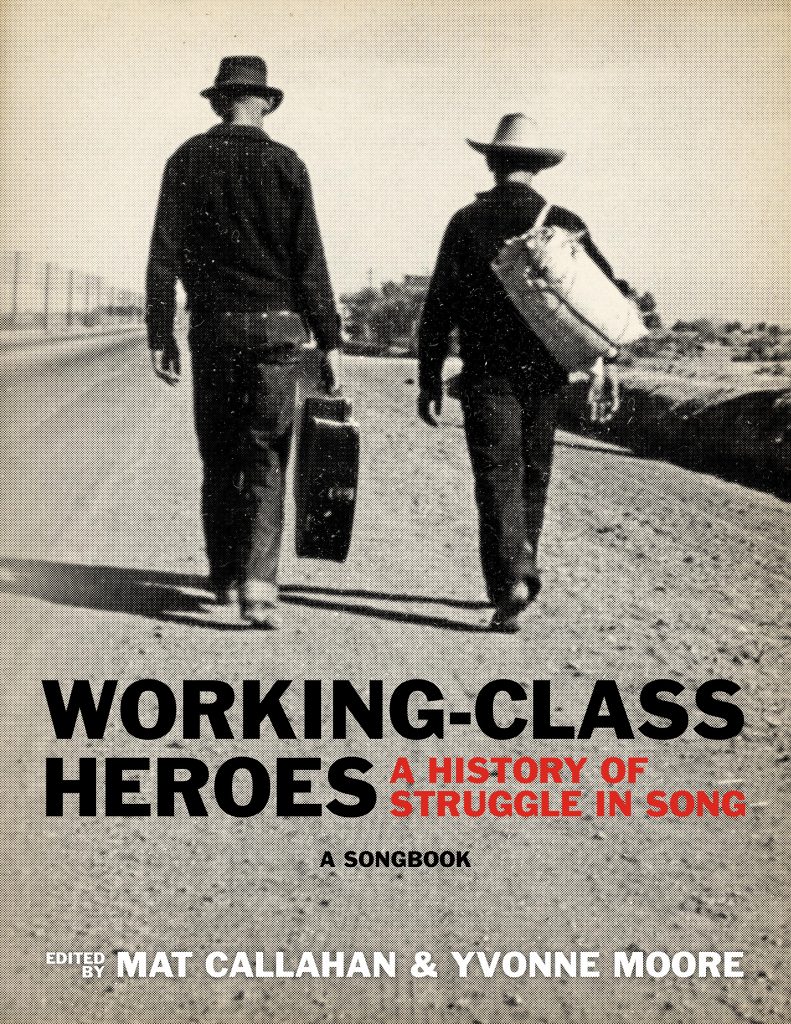

Mat Callahan and Yvonne Moore, Working Class Heroes: A History of

Struggle in Song (Oakland: PM Press. 2019, 96 pages, $14.95)

Ken Burns’s recently released epic documentary Country Music was constructed on the observation that this major stream of American popular culture originated with and was propelled by working class artistry. As a commercial genre, country music (once called “hillbilly music”) began with late-1920s records made by the Carter Family, Jimmy Rodgers and a few other Appalachia based performers – records that immediately were big sellers. These artists, along with early stars like Hank Williams and Bill Monroe, took traditional songs, instruments and musical styles and wedded these to lyrics reflecting contemporary experience. That wedding can be found in the work of all succeeding generations of performers and songwriters who identified themselves with the genre.

Ken Burns’s definition of country music is broad and embracing. Just before I watched his public television series, I received the songbook/CD packet Working Class Heroes: A History of Struggle in Song, which I had agreed to review. The juxtaposition was startling. For this collection, curated and performed by Matt Callahan and Yvonne Moore, shows us that the artistic impulses that gave rise to country music as a genre were, at the same time, producing a body of consciously radical anti-capitalist music in the American South.

Union songs accompanied the rise of unions and mass strikes during the nineteenth century. The Industrial Workers of the World (“Wobblies” as they came to be known) fostered such songwriting and singing – as well as other cultural expression by their worker members – more than any predecessor union. The Wobbly “Little Red Songbook,” regularly updated, could be found in the pockets of thousands of its hobo members. The song lyrics were class conscious anthems, set to the melodies of folk songs and hymns that everyone knew. In cities like Seattle, Salvation Army bands blared from the street corners frequented by timber workers and other migratory laborers – so the Wobblies competed with their own bands, singing revolutionary parodies of the “Starvation Army” hymns. Wobbly bards, especially Joe Hill and Ralph Chaplin, wrote songs that are still among the most familiar to labor activists.

In the 1920s, when the Carter Family and Jimmy Rodgers were beginning to reinterpret the folk songs of the Southern mountains, Appalachian men and women, raised in traditional culture, were working in southern mines and textile mills.

Callahan and Moore have curated a selection of these songs to make a CD featuring fresh and appealing musical renditions and an accompanying songbook/essay. The title of the project – Working Class Heroes – foregrounds one of their primary thematic interests, which is to make known the song making of several specific working-class troubadours. Just as Ken Burns’ documentary instructs us about the working-class origins of the great country music artists, this project demonstrates the political – as well as artistic – creativity of the labor activists who made the songs they’ve collected. In Harlan County Kentucky, in the midst of armed conflict between coal operator gun-thugs and striking miners, Aunt Molly Jackson and her half-siblings Jim Garland, and Sara Ogan Gunning, were writing songs to tell about their plight and inspire their fellow workers. In Gastonia, North Carolina in 1929, Ella May Wiggins, mother of nine, was a key organizer in the Loray Mill, the largest textile mill in the world. Ella May wrote and performed militant songs of her own making; she was murdered that year. Joe Hill, a Swedish immigrant, became a Wobbly organizer and wrote enormously popular songs featured in the Little Red Songbook. Joe Hill was famously convicted on a murder charge in Salt Lake City and was executed in 1915. In 1935, a mass strike of African American and white sharecroppers swept the Southwest. John Handcox, one of its key organizers, very purposefully wrote and used songs to inspire and rally the strikers. Threatened with lynching, Handcox was forced to leave the fields, but some of his songs became staples of union organizing in the decades since.

These are the “working class heroes” whose songs are featured in this project.

The book accompanying the CD is called a “songbook” but it is quite a bit more. The authors give us capsule biographies of their “working class heroes,” extensive bibliographic material for each, the music and lyrics for the songs, along with useful annotations.

Finally, the authors have written an essay about the political meanings of their project. They foreground the fact that the song makers – they are presenting were ideologically conscious members of radical organizations. Ella May Wiggins and the Harlan County Garland family identified with the Communist Party (CP); John Handcox was an organizer for the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, which was supported by the CP and other left groups. How these “indigenous” artist/ organizers came to such CP connections is not detailed in their essay, but the connections are seen by the authors as contradicting the notion that the CP and its ideas were historically irrelevant.

The songs collected here (and some of the other documentary material embedded in the project book) provide graphic suggestions of ways that radical class consciousness was expressed by indigenous working class cultural producers. Callahan and Moore do not provide much evidence about whether and how these songs figured in the everyday awareness of the workers whose struggles inspired them.

The authors argue that the songs they have selected are not just museum pieces – that they have contemporary relevance. There is no doubt that their effort to enable us to hear and sing these songs and to learn about these song makers has resulted in a remarkable educational and political resource.