PM: GOD’S TEETH AND OTHER PHENOMENA is the story of a writer, Jack Proctor, unravelling as he is forced to stop his own work to coach others at an elite residency, the book is uproariously funny and a profound critique of the state of contemporary literature. I found myself laughing out loud reading GOD’s TEETH more than while reading any of your other novels and stories. Can you talk a bit about the place of humor in your work?

JK: Humor derives from interaction, from a relationship. When somebody reading a book bursts out laughing, they are in a relationship with the fictional character, the situation, the words on the page and also the author. The reader has to bring his or herself to the experience.

We can identify Jack Proctor as an artist, as well as a writer. I reckon other artists, no matter their medium, will identify with much of the basic nonsense he experiences. But it is far from exclusive. Class, race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality are essential ingredients in the relationship between writer and reader. From this relationship irony derives and develops, and where irony exists fun is never far away.

The work that an artist creates is an expression of their own humanity. Immediately conflict arises. Anglo-American society is based on the suppression of the individual voice. So art begins from that contradictory footing. This is hilarious in itself, the actual situation, because it is so ridiculous. It’s not hilarious because it is funny it is hilarious because it is utterly absurd, a shocking contradiction in terms.

People like Jack Proctor persist in expressing themselves to the full extent of their humanity, so they are always a problem. And potentially they can be dangerous, as far as authority is concerned. Authority at all, be it political, religious or societal. The more authentic an artist the greater the likelihood that the establishment will treat them as naughty children who don’t do as they are told.

PM: There are certain authors, Beckett, Kafka, Joyce, Céline to name a few, who are written about with such seriousness, the humor in their work is often ignored, even when it’s central or essential to the work. Can you talk about your own work within this tradition?

JK: A modicum of empathy is necessary and it is this absence of empathy which is the major problem. Anyone who reads Kafka’s work and has experienced the horror of struggling against the full might of the State will have grounds for empathy. These readers will find the irony without too much of a problem. Think of Jarndyce and Jarndyce and the workings of the legal system in the later novels of Charles Dickens, or the bureaucracy in Nikolai Gogol, or in Dostoyevsky. Remember the impact of Dickens on Kafka – he saw his first novel, Amerika, as his own version of David Copperfield.

Kafka’s work is intrinsically political. It cannot be separated from the horrors of the society he lived in. I see Beckett and Joyce in different contexts. Their struggle was within and through language, both as Irishmen at a time when their own society and culture was dominated by two of the more malign influences, the State and the Church. Beckett is from one side and Joyce the other, but both were of the middle and upper reaches.

Mainstream critics find it very difficult to escape their own prejudices. They cannot rid themselves of their own value-systems, and enter into the “foreign” novel as their own person, down to the bare-bones, human being to human being. And if they don’t do that then empathy is not really possible. Without empathy there can be no irony. Without irony there can be no fun.

PM: You’ve written and spoken your entire career about liberation struggles and linguistic colonialism and have taken a firm stand against the State. Can you talk a bit about the role of the artist in the struggle for liberation today?

JK: Our use of language is central to the struggle for liberation. In other cultures, liberation struggles have always seen the use of language as central. Think of South America, Africa, the Indian Sub-continent, the middle east and elsewhere. There are countries where the use of indigenous language is against the law.

In most every society artists are no different to the rest of the population: outsiders do best if they assimilate. State authority preaches how crucial it is that written work is “readable” by all English-language users. Writers learn to make their language conform to Standard English literary form. And, of course, this just happens to be the voice of authority itself, the Standard Voice of the Ruling Class.

The study of language at this level is the study of imperialism. The cry for Unity at all costs is always an attack on indigenous people and other minorities – and in this context working-classness is a minority. But consider that working-class language is generally the language where indigenous forms will appear. So-called working-class slang from Glasgow features clearly the rhythms and sounds of Norse and Celtic languages, as well as Anglo-Saxon. Attacks on working-class languages is always an attack by an occupying force.

African literature offers a strong insight into what happens, we can stay with the work of Nigerian writers, consider people like Tutuola and Saro-Wiwa – obvious examples. Where writers work in different kinds of English, using different rhythms and patterns, ones that are based and derived from indigenous African languages. It gives “English” a different feel altogether but it also becomes possible to write from within their own culture, even while using the voice of the Imperialist.

PM: Who are some writers who are working against this?

JK: Writers such as Tutuola and Saro-Wiwa are revolutionary: their voices have hijacked the narrative. One of the greatest writers of the past fifty years is Ayi Kwei Armah. The obscurity of his life as a writer indicates the paucity and utter dishonesty of the Anglo-American literary establishment.

PM: Jack Proctor, the protagonist of GOD’S TEETH finds himself caught in a number of absurd conversations with writers, students, administrators about writing, the act of writing, the purpose of writing. Do you think there is a fundamental misunderstanding about what literature is and what it does?

JK: Most writers have wide-ranging experience: bar work, factory labouring jobs; working in stores, cafes, fast-food outlets, driving buses, taxis. Some take on a Writer-in-Residency position. Jake is one of them. He prefers that to mixing concrete for ten hours a day under the watchful eye of a bad-tempered boss.

Unfortunately, he is at loggerheads with many students and other aspiring authors he meets in community-based classes, groups and workshops. And he tends to drink too much red wine in awkward situations. Unfortunately, this leads him into blethering about what he truly believes, and that’s a disaster in mainstream literary circles.

Jack begins from a different understanding of how poetry, stories and plays are created than the understanding in Creative Writing programs, where the process in general begins from a fallacy that creativity is learned behaviour. The majority of students he encounters are taught that the best way to create a piece of art – literary or otherwise – is to study the work of the great artists. Imagine students of classical music being told that the way to write a great piano concerto is to go straight home, switch on the computer and go to iTunes, listen to a bunch of great piano concertos, then go out and buy a set of keyboards and compose one of their own.

This kind of foolishness means anyone at all can be a Creative Writing tutor. They don’t need to know a single thing about making a work of literary art, all they need to know is how to be an audience.

Instead of using the rewards & punishment scheme found in the Anglo-American education systems Jake hopes to lead them out of the darkness by illustration and by conversation. In that he is like many another teacher, pessimistic, but his methods aren’t, and if those close to him describe him as an eternal optimist maybe they would have more insight than the man himself.

PM: You’ve been called the “Greatest living British Writer” and one of the Greatest Modernist Writers, and like your protagonist Jack Proctor, you were awarded one of the most prestigious awards given a writer. Is there a central conflict in being lauded and awarded by a literary establishment that works to exclude radical writers?

JK: I doubt if the literary establishment has to “work” to marginalize writers and artists they consider “radical.” They simply ignore what doesn’t accord with their own interests. If that doesn’t work and they have to do something then they do the minimum.

I have no inner conflicts at all. I’ve been fortunate to receive awards. If, like most writers, I’m skint, I shall welcome any offer. Some offers are silly, they rely on prestige rather than a decent financial return. There’s no point selling-out for a pocketful of loose change, if you’re going to compromise it is better to wait until somebody offers you a decent bribe.

PM: And Jack Proctor and his prize?

JK: Jack Proctor was awarded the Banker Prize for an early novel he had written. Wherever he goes in the world from then on, he is defined by that, not the man who shot Liberty Valance but the foul-mouthed illiterate who hijacked that year’s prize. This is a similar to myself. I was awarded a Booker Prize for an early novel. I had no idea they would use it to beat me up. I don’t think that had happened before.

My first novel back in 1984 was not in any Booker longlist or shortlist yet the Chairman of that year’s panel of critics took the opportunity to name it from the pulpit. He described it as one of the worst novels of the year, and said it “was not even written in English.” Five years later my third novel made the Booker shortlist. Five years later than that my fourth novel was awarded the actual prize. That was in 1994. Since then, I have written another five novels, and not one of the five has ever made a Booker longlist never mind shortlist.

This is an unprecedented accolade. I accept it with grace.

PM: Is it possible to create art within the literary establishment?

JK: The Anglo-American establishment has major difficulties with major artwork altogether. It wants to admit the great traditions in literature but in doing so they are forced to concede the right to challenge and overthrow the values of a suffocating authority. Unfortunately for the establishment the stronger artists always make a challenge, in one form or another; not only do they write of people from within the lower areas of society they work from within the languages of these same communities. They do not assimilate. This non-assimilation is especially dangerous because it is formal and it involves how we use language. It overthrows the established order, the hierarchy. It highjacks the third-party narrative, the so-called God-voice.

From the existential tradition in literature writers learn to develop through the very form itself. Authority can be challenged. Outsiders are allowed in. This is why writers are so appreciative of the work of Dostoyevsky, Kafka, Beckett, Knut Hamsun or Gertrude Stein. It clears the path for those who are attempting to operate from different value-systems; anti-homophobic, anti-sexist, anti-elitist, anti-racist, non-sectarian.

The Anglo-American literary tradition is built on the language and values of higher end Anglo-American society. Embedded within it we find most any sentiment we can describe as WMASP (white male Anglo-Saxon protestant). A Writer who throws doubt on these values is an enemy. Those who make the challenge from within the infrastructure are dangerous. I mean by that those writers who take apart the orthodox and do whatever the hell they want with it. In other areas of society this could equate to revolution.

It is a most crucial part of the struggle against imperialism, resisting the imposition of control, taking away the right of the individual to live, breathe and communicate. When people are not allowed to speak or write in their own language, they are being denied the right to exist as an ordinary human being. In literature readers can enter a conversation with somebody who died a hundred years ago. Dialogue is at the heart of what it is to be human.

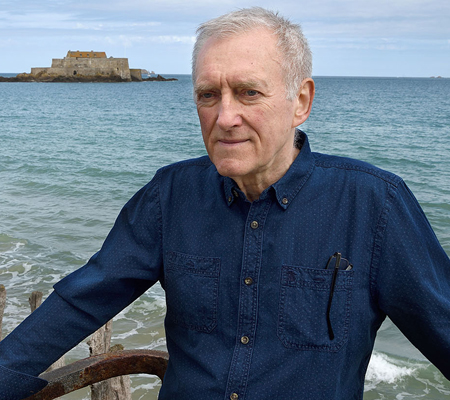

About the Author

James Kelman was born in Glasgow, June 1946, and left school in 1961. He travelled and worked various jobs, and while living in London began to write. In 1994 he won the Booker Prize for How Late It Was, How Late. His novel, A Disaffection, was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Fiction in 1989. In 1998 Kelman was awarded the Glenfiddich Spirit of Scotland Award. His 2008 novel Kieron Smith, Boy won the Saltire Society’s Book of the Year and the Scottish Arts Council Book of the Year. He lives in Glasgow with his wife Marie, who has supported his work since 1969.