Interview by Linda Mahal

Cover photo by Constance Faulk

Stonecoast Faculty Member Cara Hoffman is the author of Running, a New York Times Editor’s Choice, an Esquire Magazine Best Book of the Year, and an Autostraddle Best Queer and Feminist Book of the Year. She first received national attention in 2011 with the publication of the feminist classic So Much Pretty, which sparked a national dialogue on violence and retribution and was named a Best Novel of the Year by the New York Times Book Review. Her second novel, Be Safe I Love You, was nominated for a Folio Prize, and named one of the Five Best Modern War Novels. A MacDowell Fellow and an Edward Albee Fellow, she has written for the New York Times, The Paris Review, Bookforum, Bennington Review, The Daily Beast, Rolling Stone, Teen Vogue and NPR. She has been a visiting lecturer at St. John’s, Goddard College and Oxford University, and is a founding editor of The Anarchist Review of Books.

Well-known for her transgressive literature seminars and experimental workshops at Stonecoast, in which writers work with ink, wite-out, and fire, Hoffman co-founded the new print-only magazine The Anarchist Review of Books with Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore in 2020. ARB invites readers “to dream, to debate, to see, to plot and ultimately to act.” Produced by a global collective of artists, philosophers, and social critics, ARB is available by subscription and at independent bookstores across the United States and is provided at no cost to people who are incarcerated.

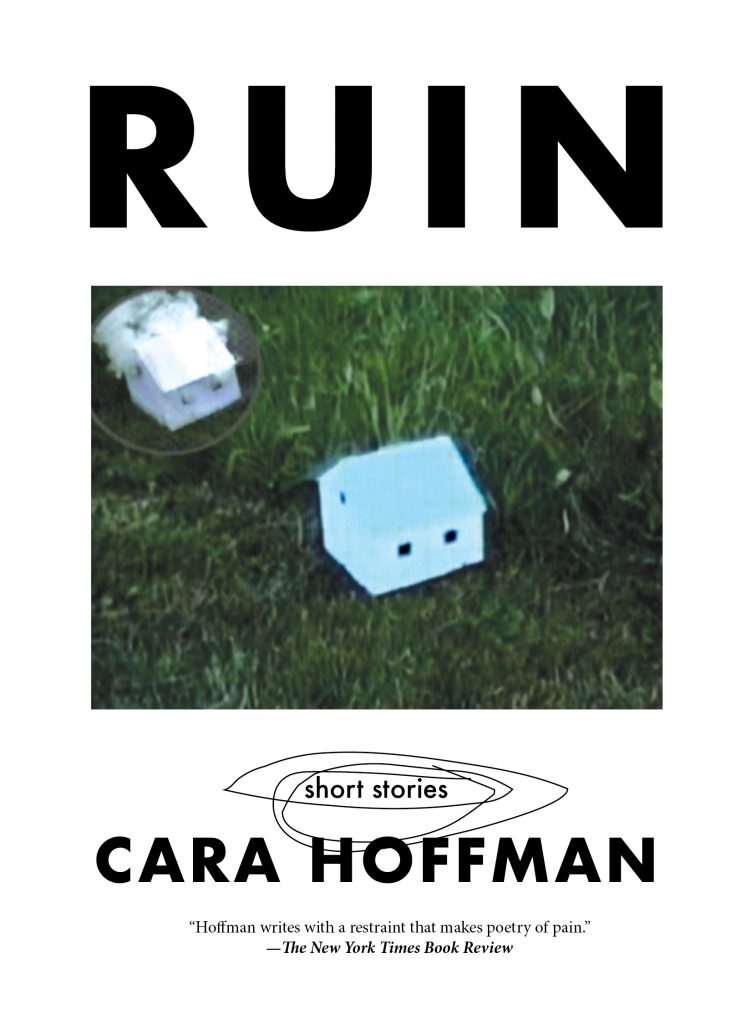

From her home in Athens, Greece, Hoffman granted Stonecoast MFA the following interview centered on her new fiction collection RUIN, forthcoming from PM Press in April 2022. Nick Mamatas (The People’s Republic of Everything) observes, “If there is such a thing as ‘anarchist fiction,’ it must be fiction that breaks all the rules of time and space, of realism and the fantastic, of fact and feelings. RUIN is true, exciting, anarchist fiction.”

Hoffman’s “Dechellis,” a short story from RUIN, appears in the current issue of Bennington Review.

“In time they’d come to eat flour made from insects, replace their failing hearts with the hearts of pigs. They would huddle in cool towers around their devices, watching aerial footage of vineyards on fire, orange as a forge, forests reduced to charcoal.

They said no one could have predicted the disease that followed the disease.”

– Cara Hoffman, “History Lesson,” from RUIN

RUIN feels like the book that’s been writing itself in the minds, or the collective mind, of those who have responded to the unfolding of the 21st century with both horror and hope. RUIN feels like an answer to a prayer. You’ve taken our fear, rage, despair and love and made story of the senselessness, indexing so much of what we’ve witnessed, but transfiguring it.

CH: Thank you, that’s very kind.

What was it like to write this book, at this time? Was it exhilarating, or a heavy lift, or some of both?

CH: It was a pleasure to work on RUIN. It’s always a pleasure to write, even if it’s painfully clarifying sometimes. I enjoyed researching and thinking about animal and insect life, and about art and about the history of mass casualty events, and about various forms of escape, and about soldiers and beekeepers, and dollhouse collectors, and talking animals. It was good to interview people and some of the stories are taken from life.

Can you tell us about your process?

CH: My process is something like this: I found a picture of my son’s father when he was nine years old, wearing many rubber bracelets that went nearly up to his elbows, and he looked feral and proud. When I asked him about the bracelets, he told me they were mortar casings. He’d found the mortars by the gate of his town—where there were often munitions dumps—especially in the 80s. He’d spent part of fifth grade living in an air raid shelter with a group of other children and it was good to talk with him about what kinds of games they played down there, and about navigating glow-in-the-dark markers during blackouts, and learning to assemble guns blindfolded, and eating lunch under pictures of Stalin. And I thought a great deal about the power of his imagination living in those circumstances, the life of his mind, his fashion, his drive, his autonomy. It’s been twenty-three years since I first saw that photograph. I have known him since we were teenagers. I wrote the story Strike Anywhere once before, but I finally figured out how to properly tell it this year.

These fictional stories seem to traverse a landscape so close to our present-day world that the line between fact and fiction is blurred. This disorientation between what is fabricated and what feels like impressionistic reportage simulates the cognitive dislocation of living in this time, and the necessity of navigating the deluge of information overload, disinformation, rapid change and endemic uncertainty.

Do we need a new epistemology to understand the veering of history that seems to be taking place now, and the art that it is giving birth to? Or are there paradigms for understanding these conditions already out there, paradigms that perhaps have been suppressed or forgotten?

CH: Wouldn’t that be wonderful? A new theory of knowledge? I do think there are older models for understanding, that have been buried. People interested in the suppression of intellectual and theoretical models could read Jacques LeCarriere’s The Gnostics—it’s a beautiful book. But I generally think most things are clear if you look closely. I grew up in a place that was already wrecked. A flood destroyed the town, and the place never fully recovered; there was no more industry, a dwindling population. And like most places in the U.S. it had been built over the site of massacres and then named after the communities of people who were murdered there. One could describe the landscape of this town in detail—and all of that information would be clear from the street names, the kinds of buildings, the surrounding woods, the meth labs, the gutted downtown, the way the people look and dress and speak. And the beauty, the sense of possibility, would be there too—in nature and also in people. Nothing is really hidden. There’s nothing to add or explain. I think the catastrophe of America, and the struggles of those who live there, is playing out in plain sight.

The following excerpt from your story “History Lesson” is one of the many powerful passages that I keep re-reading:

“Those last years in the city, when people would pay for a human voice to put them to sleep at night, when people would pay for a human voice to tell them how to breathe, I was dying for a silence that was no longer possible. And not even the ghost of the landscape, the ghost of the neighborhood remained. We were not watching things carefully in those last years, we were keeping our heads down and pretending there was a future. We were amassing the resources we’d need to break the gravitational pull. No one anticipates how fast change happens.”

Are we in the “last years” now? What is the role of the writer in this moment?

CH: I think about this, living in the center of Athens, seeing modern buildings beside 2,500-year-old ruins. I don’t think these are ‘last years’ for our species—which is so resilient. My biggest fear though is that the world will be inherited by tech-billionaires in their bunkers. This isn’t a fear based in fiction—wealthy Americans are buying luxury condos in repurposed nuclear missile silos fifteen stories underground. I hope that there will be work made today that can survive a new dark age, and that it won’t be made by rich Americans eating hydroponic vegetables and lab-grown meat while watching surveillance feeds of a burning landscape from inside hermetically sealed luxury. But after seeing the cave paintings in Pech Merle and Altamira, I’m pretty optimistic that humans will be able to make work even if they are sharing a cave with a bear during an ice age. The role of the writer is to write. I don’t think it’s different now than at any other time in history.

How would you guide writers who want to write about cataclysmic or monumental events such as September 11 or the pandemic? What makes for good writing in response to these events, and how can one avoid the banal or the melodramatic?

CH: This question makes me think of Kevin Carter— the photographer famous for his work on the famine in Sudan. He won a Pulitzer for a photograph he took of a starving child being stalked by a vulture, which was published in the New York Times in 1993 and appeared directly next to an ad for Tiffany’s—an image of a 2 ¼ inch high sterling silver circus elephant selling for $1,050. Carter said he chased the vulture away after taking the picture, and that minutes later he boarded a plane. What he didn’t do was take the child to the UN food center. In 1994 he killed himself.

As a journalist and as a novelist I’ve written about some horrible things and I have serious questions about what it means to aestheticize pain, and who is doing it, and why. I think important questions to ask before writing about tragedies are: why am I the one to tell this story? Why am I compelled, what are my intentions? Who am I doing this for? Where will it appear?

I think I answered the craft part of this question above when I talked about detail and looking closely.

What gives you hope?

CH: I’m optimistic about thought and art and language, and about the number of new projects I see that exist offline. I have read some wonderful books lately. Morgan Talty [Fiction ’19] has a collection of linked stories coming out from Tin House called Night of the Living Rez, which I was lucky enough to read when he was working on it for his thesis at Stonecoast. The experience of diving into that work was like first picking up a novel by Marguerite Duras, or like reading Denis Johnson’s Jesus Son. The prose is masterful. It’s brutal and funny and smart and has a genuine warmth that’s rare, especially in contemporary commercial fiction. Morgan’s book has done a lot to restore my faith in the future of literature.

What are you working on now, or next?

CH: I have three books forthcoming: a collection of essays; a non-fiction book about Exarchia, and a new novel. Each project is at a different stage of completion. I’m also finishing the edits for the Greek translation of Running, which will be out in spring 2022, around the same time as RUIN comes out in the U.S. And I’m working with the editorial collective of The Anarchist Review of Books on our winter issue. And I’m reading and studying Greek.

To learn more about Cara Hoffman and her work, please see her Stonecoast MFA faculty bio and her author website. RUIN is available for pre-order from PM Press.

Photo credit: Marc Lepson

Photo credit: James Newman

Photo credit: James Newman

Learn more about Cara Hoffman and her forthcoming work with PM Press HERE