by Sam Royka

Industrial Worker

August 27th, 2021

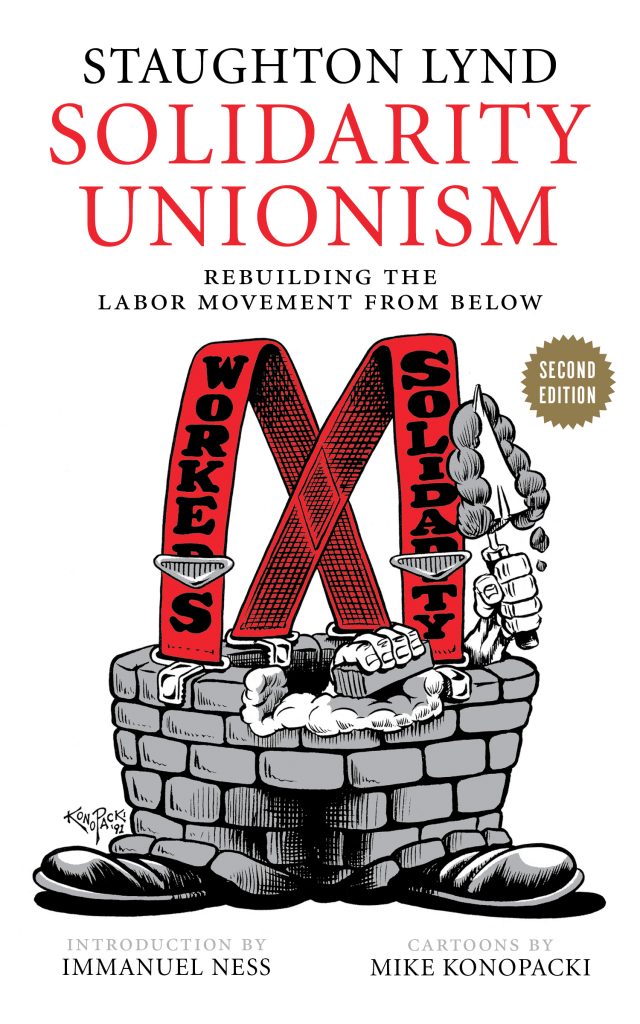

Solidarity Unionism: Rebuilding the Labor Movement from Below was written in 1992 by the civil rights and peace activist Staughton Lynd, who received his bachelor’s degree from Harvard in 1950 and doctorate from Columbia University ten years later. In a recent interview with Industrial Worker, Lynd reflects on how some issues in the labor movement have changed since his book was first published.

Solidarity Unionism Defined

To condense the idea of solidarity unionism into a sentence: If a worker wants eight-hour shifts, but management wants 12-hour shifts, the best way for that worker to achieve their end is not to negotiate, but to walk off the job after eight hours, argues Lynd. The concept of a single, comprehensive contract that governed negotiation for a set number of years came from the Congress of Industrial Organization unions in the 1930s. Though thousands gained bargaining power through these comprehensive contracts, workers were confronted with two major issues embedded in contract clauses.

The first of these is the “Management Prerogative Clause,” which says that the operation of the business is the legal right of the employer alone, meaning that the employer does not need to bargain with the union regarding, for example, the tearing down of factories. This clause means that employees can bargain for benefits, but often cannot further ensure jobs — that being the exclusive authority of the employer.

The second problematic clause for workers is the “No Strike Clause.” Martin Glaberman, a writer influential to the idea of solidarity unionism, believed that workers could strengthen a union not by placing more issues within the framework of collective bargaining, but by simply retaining the freedom to take direct action regarding those problems, as detailed in his 1952 pamphlet, Punching Out.

Together, these two clauses surrender workers’ rights to influence investment decisions and participate in collective direct action by strike or slow down. In addition, the relationship between these two clauses and “Dues Check-Offs” — employers automatically deducting union dues from workers’ paychecks — should be addressed, argues Alice Lynd, wife of Staughton and co-author of Rank & File: Personal Histories by Working-Class Organizers. Dues Check-Offs are largely unnecessary, she says, citing an example of a small, independent union of visiting nurses which she helped organize. Instead of having a formal way to collect dues, when the group needed money, they would pass a hat and those who could give, would give.

Changing Struggles

The National Labor Relations Board, a federal agency for unions and employers, was created in 1935. It “embodies the assumptions of the people who created the present structure of labor law in the 1930s,” says Lynd. In the years since its inception, the usefulness of the NLRB to the labor movement has varied depending on the political climate and its leaders, appointed by the sitting US President.

A fundamental question with the national labor apparatus perennially is who is included, explains Lynd. Today, labor law is beginning to be redefined in the arena of independent contractors. A recent example of this struggle is Uber and Lyft drivers in California organizing a 24-hour strike for better wages and congressional support of the PRO Act. At this time, the drivers are involved in an ongoing misclassification lawsuit.

“Employers across the United States are doing their level best to say, ‘No, these are not employees, these are independent contractors,’” says Lynd.