At the launch of Selma James’ latest book, Angela Cobbinah finds the 91-year-old as resolute and sagacious as ever

Camden New Journal

August 13th, 2021

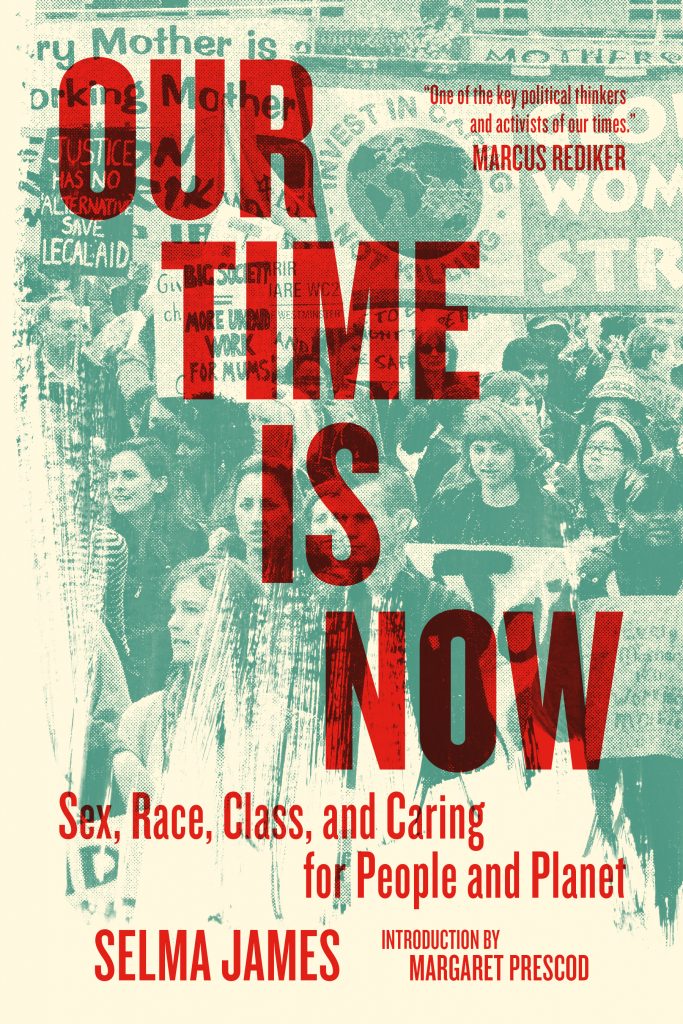

IT is only to be hoped that someone who has been a political activist for more than 70 years would have an expansive view of the world. During a speech to launch her latest book, Our Time is Now, Selma James did not disappoint, going from the International Wages for Housework Campaign (WFH) that she founded nearly 50 years ago, to slain Black Panther leader Fred Hampton and Tanzania’s Ujamaa movement, and much else in between.

Just turned 91 and looking remarkably straight-backed, she spoke without notes, repetition or hesitation, displaying the same passion that has driven her to fight on the side of the powerless in all its manifestations over the decades. “We get tired but we don’t burn out,” she told her audience at OffSide Books in Kilburn. “The reason why we do not burn out is because we are building a movement.”

When she launched WFH in 1972, she was scorned by feminists’ groups who said that women going out to work was the path to liberation, not being paid to be stuck at home. However, this was to miss the point. “Housework” is shorthand for the vital work of reproducing and caring for the next generation but which under capitalism leaves women impoverished. If women go out to work, as they invariably must in order to survive, they are doing two jobs, one they get paid for and one they don’t.

The idea may sound radical but it is not new. In the book, James pays tribute to the “neglected” suffragette and social reformer Eleanor Rathbone, whose long campaign to secure financial support for mothers was finally acknowledged when family allowance, now child benefit, was instituted in 1946 as part of the new welfare state. Although limited and, thanks to government cutbacks, no longer universal, the principle of financial recognition for “carers and care givers” remains.

“Eleanor is an inspiration for all of us campaigning for a more humane society,” she says in a chapter reproduced in Our Time Is Now from an article she wrote for the Guardian in 2016.

James is often dismissed as a fringe figure on the shrieking side of the barricades, but the more time goes on, the more a lot of what she says makes basic sense, as the book underlines. It is a follow-up to Sex Race and Class, which a decade ago memorably charted her political journey from Brooklyn factory worker, teen mum and fringe Trotskyite to international feminist and Caribbean-based anti-colonial activist alongside her husband, the Trinidadian scholar CLR James.

Included this time round are mainly her later writings that set out her political thought and the nature of her campaign work, how WFH departs from the feminism that only demands that women break the glass ceiling to achieve positions of power and wealth.

Equal pay is all well and good but the caring, cooking and cleaning work that goes on in the home remains “unwaged” – a term James coined in her redefinition of the working class – and therefore undervalued.

“Production of things for sale is the priority but the reproduction of the human race is not,” she neatly states.

She is a great admirer of leaders like Hugo Chavez, Jean-Bertrand Aristide and Julius Nyerere, who explicitly recognised this, and writes with wistful fervour about Nyerere’s 1960s Ujamaa programme that placed women at the forefront of the new society he was attempting to forge. Beyond this, there is a fascinating reappraisal of two of CLR James’s books, The Black Jacobins, his masterful account of the overthrow of the slave regime in Haiti, and Beyond a Boundary, his meditation on cricket as a metaphor for art and anti-colonialism.

In Beyond Boundaries, a 2019 Q&A, Selma also talks about her marriage and political partnership with James, revealing how she had to go back to working in a factory when she joined him in England in 1955 following his deportation from the US during the McCarthy witch hunts, and the isolation she felt. “CLR knew Britain because he had lived in Britain as a British colonial … [It] was an entirely foreign life to me, and I had to find and make my own life, and I did,” she declares.

The book’s subtitle is the rather cumbersome Sex, Race, Class and Caring for People and Planet. James, though, writes as she speaks, clearly and straight to the point, with plenty of wry asides. This is about you, whoever you are and wherever you are, she seems to be saying. WFH comprises a network of groups based at the Crossroads Women’s Centre in Kentish Town.

They are described in the book as “autonomous organisations”, which are united in fighting all forms of discrimination, operating on the basis that the power of one struggle reinforces the other. Also referred to as Global Women’s Strike, their international work in recent years has extended to Haiti and Palestine.

Closer to home, when Jeremy Corbyn was elected Labour leader in 2015, the campaign turned its attentions to getting him into 10 Downing Street. The reasons he lost the 2019 election are examined at length, with James berating the timidity of Labour leadership in repudiating charges of anti-semitism against it.

Painful as that defeat was, she points to the grassroots movements that have since emerged to reshape the political landscape around the world like Black Lives Matter and climate justice. “People are starting to find their voice to … understand that they can actually have an impact,” she writes, as admirably resolute as ever.