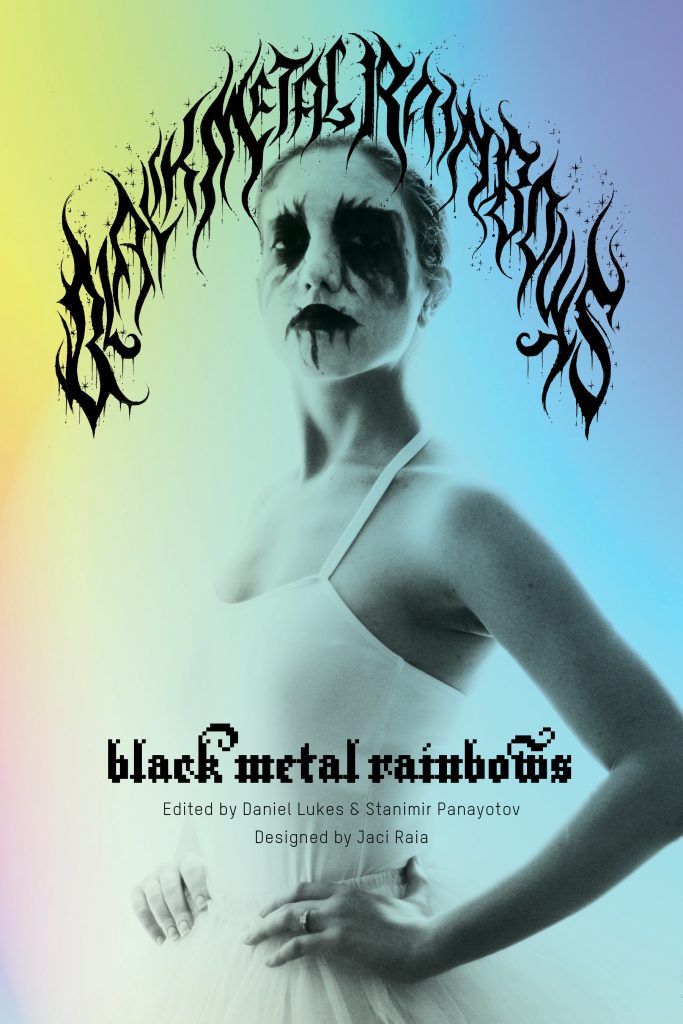

Writer and editor Daniel Lukes discusses creating inclusive spaces within a subculture and his anthology Black Metal Rainbows, which attempts to shine a sparkling light on black metal.

By J Bennett

The Creative Independent

The [heavy metal sub-genre of] Norwegian black metal was created in the deep underground [in the early ’90s] by a small and fairly closed circle of musicians. There was a sense of exclusivity there. Today, we’ve got wide-release movies being made about it, but there are still people who resist making black metal open and inclusive. Do you think it’s bizarre that the fans, for lack of a better term, are trying to dictate who can listen to this stuff? Or who can create it, even? In that regard, I’m thinking here about Black musicians like Zeal & Ardor or trans artists like Liturgy, neither of whom was exactly welcomed with open arms when they first appeared—and continue to have detractors seemingly based on the fact that they’re not white men.

Black metal is paradoxical in that it’s underground—it’s raw, it’s ugly—but it also reaches for the stars. It’s lo-fi, it’s tinny, but it also has this orchestral quality to it. I think black metal wants to have its cake and eat it. It wants to be exclusive and underground, but they want to be rock stars. It contains these multitudes and these paradoxes. I can totally relate to people wanting their exclusive club, in a way. When you’re a teenager—and I think the teenage mentality very much runs through black metal—you feel the world doesn’t understand you. You feel the normies are all on a different planet.

You can’t connect with them, so you want to have something which is yours, something which is an exclusive club where you and your friends can laugh at the normies and think you’re smarter than them because you’re listening to this exclusive metal. I think that’s fine. It’s when you mix that with ideas of saying who can and who cannot listen to the music—at that point it starts to get fucked up. That’s what we’re pushing against.

One question we get is: “Are you trolling? Is this book just an elaborate troll?” But I would call this book a love letter to black metal. We love black metal—that’s why we made Black Metal Rainbows. We’re not poking fun at it; we’re not mocking it. We’re not trying to dilute it or weaken it. We don’t think that any of the things we’re saying removes any of its edge or essence. We put a lot of energy and time and money into this book because we love black metal. And everyone is welcome to join this community—except for Nazis. Anyone is welcome unless you hate us.

One of the phrases we came up with [in the book] is, “Black metal is for everyone.” In a sense, I think black metal is for everyone—or anyone. It should be open to anyone—anyone can listen to it or play it and do anything they like with it. Whether they will or not is another question though, because the harshness and aggression are still there. You can make it as soft as you like—you can make it black-gazey and so forth. The models you’re still relating to are ones of heaviness and harshness and so forth. I think this to and fro is what makes it interesting.

You got into black metal as a teenager in the ’90s, when the sensationalism of it was at its peak. You likely read all the well-documented tales of arson, murder, and suicide that went on within the early Scandinavian scene. Was the element of danger part of the attraction for you?

I don’t know. I was living in Italy at the time, so I did start picking up [the British metal magazine] Kerrang!. Then I would go on to write for Kerrang!, so all this sensationalizing of criminal activity as a part of rock n’ roll, it’s something I’ve thought about a lot—especially now, making this book. It seems like a lot of behaviors which were thought to be cool or edgy back then, we’re actually seeing that this stuff has real consequences and hurts real people.

I think our whole concept of edginess has changed. I think in the ’90s there was this sort of tolerance for the white male artist lashing out. It was seen as acceptable in ways that now it’s not. I guess as much as I was attracted by the edginess, I never really thought too much about it. It wasn’t so much that burning churches seemed cool to me. I never was particularly interested in that part. I don’t know, what about you?

The churches these guys torched in Norway were beautiful buildings that date back to the 12th and 13th century, and I think it’s a shame to burn them down. As far as the murders go, they’re also terrible—there’s no way around it. You have Bård “Faust” Eithun, a [Norwegian] black metal musician who murdered a random homosexual man and another [Norwegian] musician who murdered a musician he knew. The murderer in that last situation was [Burzum’s] Varg Vikernes, a notorious racist, who stabbed [Mayhem’s] Euronymous 35 times or something like that.

Here’s the thing about Varg: I’ve interviewed him, and he’s terrible. If you know nothing about him—his terrible views, his terrible crimes—he’s terrible on a personal level. There’s nothing appealing about him, beyond the fact that he’s a talented musician.

You’re touching on an interesting thing here, which is the license of the artist. The [idea that the] artist is allowed to get away with anything, as it were, because artists are important. I think he’s an idiot, and I don’t know how conscious any of this stuff was, really, but I think the second wave black metal in Norway and what they were doing was some kind of extreme form of culture jamming. They realized on some level that the way they could make their mark was not just to make music, but also commit these crimes and this would put them on the map—and I think it worked.

In a sense, their hold on black metal is still something that we are struggling against with this book. It’s a struggle to get away from those guys who—yes—musically and aesthetically were important, but they also hijacked the genre for posterity, at least in their eyes. But it’s being wrested away from them, which is also something I think is worth doing.

And you know, I feel like there’s an aspect of ‘90s Scandinavian black metal that is fundamentally flawed—and that flaw is possibly a part of what led to all the extreme behavior. These were a bunch of privileged Norwegian teenagers, in the pre-Internet days, who maybe did not understand that Venom was kidding. To me, that’s always been a key premise for a lot of this stuff. They thought Venom’s faux-satanism and barbaric posturing was for real.

Yeah, one thing we want to definitely bring back is this comedic or carnival-esque element, which I think some black metal—especially in the second wave, but also beyond that—ignores. You have people taking it too seriously. Come on, you’re dressing up in corpse paint—you look like KISS. You’re shrieking and howling about being depressed in a forest. Refusing to see the funny side of it, you’re only showing half the picture.

For me, it also goes back to those Immortal videos where they’re just running through the forest. It’s ludicrous; it’s camp. Why do we have to deny that black metal has that camp side, that it indulges in its own silliness? What appealed to me about black metal is that it really kind of revels in its own absurdity and foolishness and I love that.

People online, when they hear about this book, they say, “Is this a joke?” Well, in a way, yes. In a way, no. Why shouldn’t black metal laugh at itself? Black metal wants to laugh at everything else. Black metal wants to basically burn everything and say nothing is sacred, but oh, no—black metal is sacred. You can’t laugh at that.

Isn’t that a bit hypocritical? You want to say nothing is sacred; only black metal is sacred? In a sense, the book is turning back the laughter on itself. It’s holding up a mirror to black metal and saying, “Let’s be consistent here.” Even black metal is something to be laughed at. Again, it’s kind of an ingroup/out group thing as well. If you have no investment in black metal, you can laugh at it as an outsider and say, “This a joke, this music is ridiculous. These people are ridiculous.” That’s different from laughing at it from within.

I brought up Zeal & Ardor earlier not only because Manuel [Gagneux of Zeal & Ardor] is someone I’ve interviewed for this site, but to me his work seems like the template for the kind of open, inclusive atmosphere that you’re trying to promote in black metal. Is that accurate?

Yeah, I would say so. There’s a good essay in our book by Laina Dawes, who has a great book called What Are You Doing Here?, which is basically a perspective of a Black woman in metal. She writes about Zeal & Ardor. And I know we’ve already talked about Varg, but I think the point needs to be made over and over again that however much Varg doesn’t like it, this music comes from rock n’ roll. It comes from Black music. Trying to deny that is just dishonesty. It comes from the Blues—that’s where the sonic roots of the music is. Whether it’s Chuck Berry or Jelly Roll Morton—all that stuff that’s “the devil’s music”—there’s a direct lineage to that. Black metal is an iteration of that and that’s the irony here.

Black metal seeks to deny its own Blackness in terms of African American music. That’s a point worth making. I think Laina’s essay is very much one of the key pieces of the book in that regard.

We keep talking about Norway, but you have this all around the world now. There’s so many creative projects and different takes on black metal. For instance, Deafheaven is another big inspiration for the book. The whole concept of “pink” black metal or summer-y black metal, Deafheaven is taking it in this new direction in such a bold way, and I think it’s what the genre needed to stay relevant. It felt necessary to celebrate this new age of dualistic black metal. Right now, there’s so much going on, whether it’s red and anarchist black metal, anti-fascist black metal, black gaze, black noise…there’s a lot going on.

The rainbow you’re referring to in Black Metal Rainbows isn’t confined to the artists. The contributor list is also a rainbow of diversity, which is an important part of this. There are a number of different personalities, too. What have you learned during the process of putting the book together?

This is now the third edited volume I’ve worked on, and it gets easier in the sense that what I really like is the connection and the contact with people. You’re reaching out to people and you’re connecting with them over a shared project. It’s a collaborative work, so it’s different from when you’re just a writer and you’re working on your craft. Some of these pieces already existed, and some of them were commissioned by us. You reach out to people and say, “Do you have any ideas?” You creatively work with an artist to come up with something. I think that’s what I want to do more of in the future.

I can let myself down in the sense that I can write my own works and just leave them in the computer and not push them that hard. If there’s someone else involved, it’s harder for me to let them down and disappoint them by not pulling my end. So I think what I learned from this book is also the importance of community as well. Even now, looking at the Facebook and Twitter comments from people who came across the book, they’re saying, “Yes—exactly. I’ve been listening to black metal and this resonates with me.” For me, black metal always had more to it than hate and anger and loneliness. It really is a community.

Some Things Daniel Lukes Recommends:

Divide and Dissolve – Gas Lit

Maggie Shen King – An Excess Male

Pier Paolo Pasolini – The Hawks and the Sparrows

Entheos – Dark Future

Sayak Valencia – Gore Capitalism