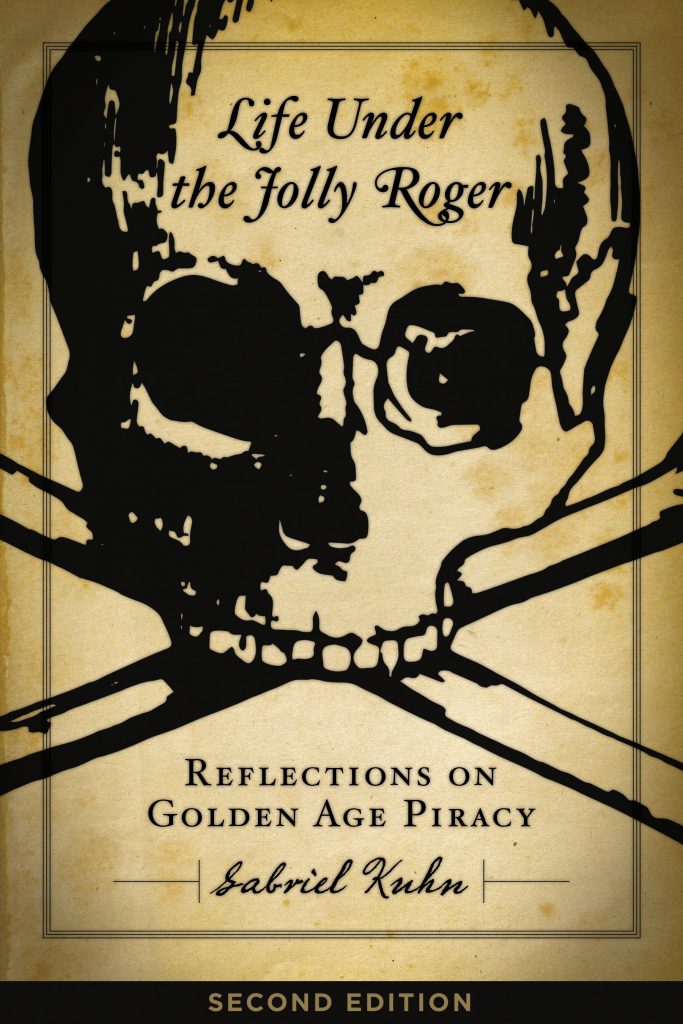

This is a political and anthropological look at piracy, buccaneering and privateers in the late 1600s and early 1700s in the Caribbean, Atlantic and Indian oceans. It’s not some rollicking tale of treasure chests, parrots and peg-legs, though real pirates always liked to frolic. Anarchists and many others have thrilled at the exploits of these pirates, but Kuhn carefully evaluates what their lives were actually like. The anarchist black flag is possibly based on the black skull and crossbones design of the Jolly Roger and that link continues to this day. Some direct-action environmental groups like Sea Shepard continue to use it, so Kuhn also discusses the pirate legacy for the present.

Kuhn carefully delineates the various European characters that inhabited the Caribbean, Madagascar and central America during this period; their temporary bases in Tortuga, Nassau and Madagascar; and their actual actions and ideas.

Definitions: Privateers were mercenaries hired by various countries to raid enemy ships. Buccaneers and log-cutters were land-based ‘primitives’ who had left the service of any nation, living on islands and coasts. Pirates were privateers or buccaneers who decided to go it alone in sea robbery. Pirates raided wealthy merchant ships from Spain, Britain, France and any other country, not really preying on small fry or ordinary people. This garnered them “Robin Hood” sympathy from many ordinary island-dwellers and coastal dwellers in the U.S. Oddly, it was the end of the wars fought between European nations that turned some government privateers into independent pirates.

THE PIRATE PLUSES

They were a motley crew of former indentured servants, ex-sailors, criminals, bankrupts, adventurers and the flotsam of various European countries who decided to form a Brotherhood opposed to all nations. Their ‘salty’ swearing and youth were rampant. An early pirate iteration was called “The Brethren of the Coast.” The Jolly Roger itself indicated their independence, rejecting kings and countries and many times rejecting nationalism. The crews decided things democratically on the ships, as captains and other ‘leaders’ of the boats were decided by vote. Booty was divided almost equally. Targets were voted on. Captains could be removed and crews split up, also by vote. They dispensed a more equal justice, unlike the European or U.S. courts. Pirates stood together as required, as this was part of the pirate ‘code’ – articles of agreement which were actually written down on each ship. Because of the clothing codes forbidding nice fabrics to commoners, pirates dressed as colorfully as they could, in the best clothing they could steal.

In some ways Kuhn compares these small groups to ‘primitive communism,’ as wealth was not accrued or hoarded. Pirates blew their doubloons in a few days after coming onshore to drink, visit prostitutes, gamble, dance and listen to music, fight and the like. Tortuga and Nassau, the Mosquito Coast, Madagascar and even the U.S. east coast were havens or partial havens for them. Even captains did not get rich, so those tales of ‘treasure chests’ are bogus. Except for necessity, no pirate wanted to be told what to do, given their experience with cruel merchant ship captains. Kuhn praises this ‘anti-authoritarian’ attitude as free individuals. They abhorred work, except when necessary, and attempted to enjoy their short lives to the maximum. They lived in conditions far better than the Royal Navy or any crushing job on a commercial merchant ship or whaler of the day.

Ever the intellectual, Kuhn references Foucault, Guevara and Mao, Guattari and Deleuze, Hobsbawn and Nietzsche in his analysis of pirate ways, including warfare. Pirates practiced a form of ‘guerilla’ warfare, but on water. Know the water and land, strike quickly, strike terror, use surprise and light-arms, fight ferociously, then disappear. The difference between this and socialist guerilla war is they never developed a real ‘base’ among the islanders or coastal inhabitants or anyone else, so their resistance was relatively short-lived. Nor did their failure to ‘breed’ help their cause, as they avoided women except for sex.

NEGATIVES

The negatives? Kuhn punctures the myth that they had equal indigenous or African pirates on board the ships. This issue is not totally clear, but many were probably servants or slaves, though their lives would have been better on a pirate ship than in a sugar-cane plantation or being killed by Spaniards. A good number of pirates actually engaged in the slave trade, which was one reason nations were irritated with them – as competitors. This was one of the rationales for bases in west Africa and Madagascar. In Madagascar the well-armed pirates were eventually driven out of their colony by the inhabitants.

Occasionally Mosquito Indians from the Nicaraguan coast were on ships as fisherman, fighters and guides, but there is little indication they were there as permanent pirates. Nor did the pirates have a view of liberating everyone oppressed by colonialism or uniting with island-based Maroons (ex-slaves) – a myth done up quite nicely in the excellent pirate series “Black Sails.” They were incapable of that kind of vision or organization. Nor is there record of many women pirates – only two – and they had to pretend to be almost like men. This was a nearly all-male brotherhood.

The pirates never produced anything, so hints that they are ‘proletarian’ are false. They lived off the backs of colonial enterprises, taking a piece for themselves. Lumpen-proletarian might be closer to it. If this all reminds you of present day ‘gangs’ – motorcycle or otherwise, that would not be amiss.

THE END

The ‘golden age of piracy’ began in 1690s and ended in the 1720s when the most successful captain, Bartholomew Roberts, was hung along with his large crew. It is estimated that at its height golden age pirates involved at least 4,000 men. The nations which had at one time tolerated pirate activities because it hurt their competitors and brought trade items, along with gold and silver, into their communities, turned against it as European (and U.S.) merchant capitalism grew and expanded. Sea roving rogues like this could no longer be tolerated in a more orderly commercial structure, so national navies flooded seas and oceans to kill, turn or capture the freebooting pirates.

According to Kuhn, their legacy is seen in such things as ‘pirating’ movies, even if stealing “Pirates of the Caribbean” would not be appreciated by the Disney© Corporation. Pirates occupied temporary spaces, and these are replicated in various short-lived ‘autonomous’ zones, such as George Floyd Square in Minneapolis or other temporary counter-culture places. In 2009 the “Pirate Party” gained votes and seats in the European Parliament. Rum runners and ‘bootleggers’ owe their moniker to this old crew. To this day, Sea Shepard, the ocean-going environmental group fighting illegal fishing and whaling, flies their version of the Jolly Roger on their ships. Then there is always culture – Keith Richards, who styles himself a rock-and-roll pirate or his silly shadow, Johnny Depp. The pirates seem to be living on…

Kuhn has read every source there is on pirates, though much detail is missing in the histories. This is an excellent introduction and compendium from a left point of view on these lefty and anarchist fore and aft-runners.

Prior blog reviews on this subject, use blog search box, upper left, to investigate our 14-year archive: “Black Sails,” “Vultures’ Picnic,” “History of the World in Seven Cheap Things.”Or other books by Kuhn: “Playing as If the World Matters” and “Antifascism, Sports, Sobriety.” Or the words slavery, gold or colonialism.

Gabriel Kuhn is an author, translator, and union activist. He has published widely in English and German. His texts have been translated into more than a dozen languages.