Punk revolution

By Miss Rosen

Huck Magazine

July 20th, 2021

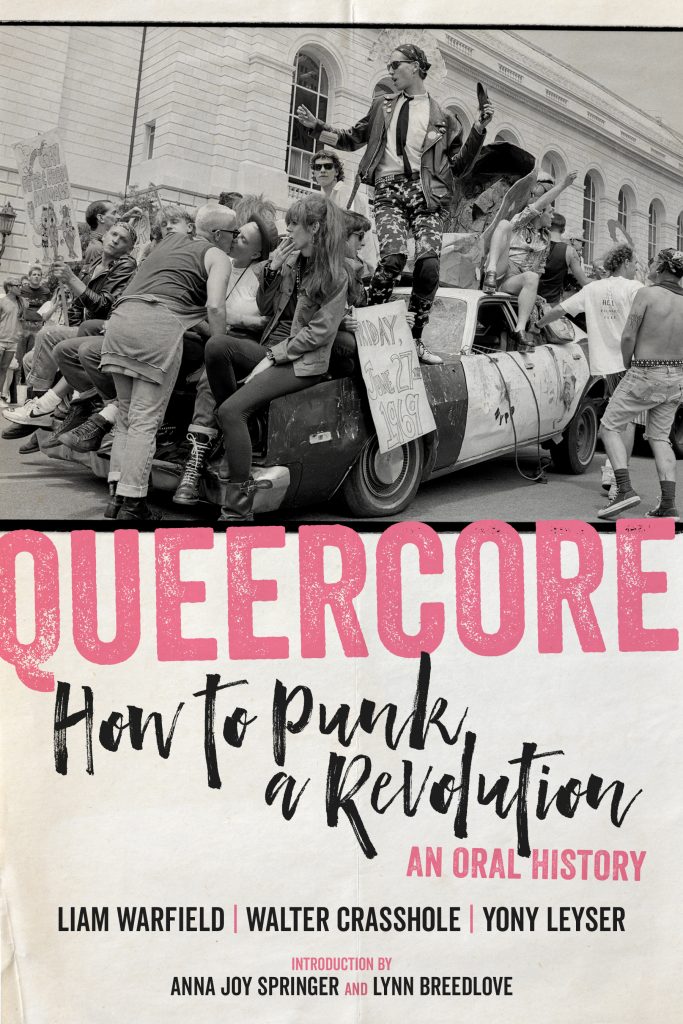

A new book is celebrating queercore, which brought together music, zines, photography, art, film, writing, performance art and style, and the people on the inside of the movement who made it an underground phenomenon.

From the very start, queer identity has been a central proponent of punk culture, starting with the name itself being jailhouse slang to describe the man on the receiving end of anal sex. By the time punk culture was named in the mid to late 1970s, it was an amorphous space of freedom, where gender and sexuality were fluid.

“In the beginning, punk rock was exceptionally gender diverse,” says Walter Crasshole, who edited the recent book, Queercore: How to Punk a Revolution: An Oral History (PM Press) along with Liam Warfield and Yony Leyser. “There were a number of LGBTQ+ protagonists in the punk scene, some who made that very clear and it was part of their identities, like Jayne County.”

Anna Joy Springer and Lynn Breedlove

Vaginal Davis and Joan Jett Blakk at SPEW 2. Photo by Mark Freitas

But it wasn’t until the mid-1980s that queercore emerged as a potent force, rising from the horrors of the AIDS epidemic, the neoliberal policies of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, and the reactionary, hyper-masculine orthodoxy of the hardcore scene.

Recognising the community no longer provided the support they needed to survive, a group of disaffected queer punks, artists, and musicians, including G.B. Jones and Bruce LaBruce, began to develop their own scene, laying the groundwork for what would become first known as ‘homocore’, then take on the more inclusive name ‘queercore’ in the early ‘90s.

Expansive in vision, queercore brought together music, zines, photography, art, film, writing, performance art and style in a revolutionary celebration of queer punk cultural forces around the globe. “They demanded and took their own space and offered it to marginalised people who might not have had access and made it easier for them to participate in these scenes,” Crasshole says.

Deke Nihilson at Homocore Chicago. Photo by Mark Freitas

San Francisco Gay Pride, No Assimilation Contingent, June 24, 1990

Queercore: How to Punk a Revolution, the first comprehensive overview of the movement, offers a kaleidoscopic view of the scene from the people on the inside who made it an underground phenomenon. Drawn largely from interviews by Lizer’s 2017 documentary film of the same name, the book features a wealth of stories from Jayne County, Penny Arcade Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, John Waters, Vaginal Davis, Kim Gordon, and Kathleen Hanna, among others.

In the tradition of punk classics, Please Kill Me and We Got the Neutron Bomb, the editors have brought together first person accounts that chronicle the culture by the people who built it.

John D’Armour (now known as Hathaway) with just announced presidential candidate Joan Jett Blakk at SPEW II in LA 1992. Photo by Mark Freitas

“Queercore is a marginalised scene within a marginalised scene that grew out of its own hard work and labour. It was not put together by record companies or TV programmers as a cohesive thing with a specific agenda and purpose. Everyone had their own experience,” Crasshole says.

“The music is the best, but it’s not made for a wide audience. It is still rather fringe. These stories shouldn’t be vanishing into the past without being continually reexamined and hopefully recycled, reused, and appropriated for new generations.”

Divine

A young G.B. Jones and Bruce LaBruce

Behind the scenes of Hustler White

Demonstration on women’s AIDS issues at the Sixth International AIDS Conference in SF, June 22, 1990