By Ian Thomas

The Comics Journal

July 12th, 2021

Bill Campbell is a writer, editor, and owner of Rosarium Publishing, a publisher focused on speculative fiction, comics, and crime fiction told through the lens of multicultural talent. Campbell launched Rosarium in 2013 with a mission to “introduce the world to itself” by giving a platform to creators who might typically be overlooked by a biased industry. This ethos is encapsulated in anthologies such as Mothership: Tales from Afrofuturism and Beyond and Stories for Chip: A Tribute to Samuel R. Delany.

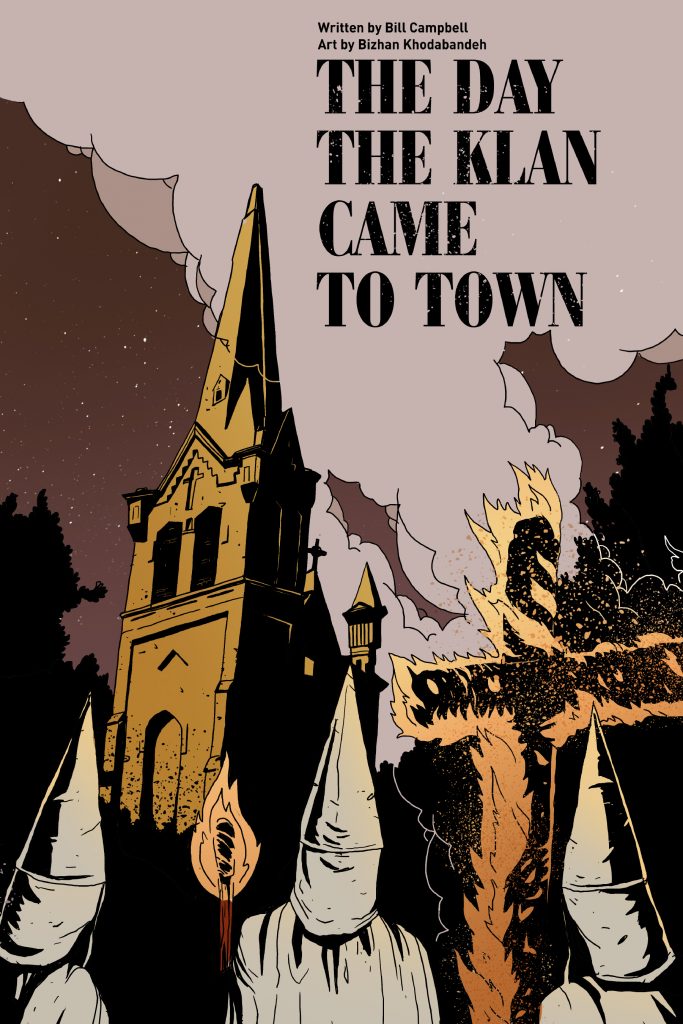

Campbell’s forthcoming graphic novel, The Day the Klan Came to Town, explores a little-known event that had been all but omitted from the history of Southwestern Pennsylvania. In his portrait of Carnegie, Pennsylvania in 1923, Campbell, along with artist Bizhan Khodabandeh, depicts a community of immigrants that must reconcile its prejudices and find common cause against oppressive forces that threaten to tear the town apart. The resulting message is that anti-racist action is a responsibility that must be taken up by the whole community and Campbell and Khodabandeh do not shy away from the high stakes and radical solutions needed to address the issues of xenophobia and racism. Needless to say that while The Day the Klan Came to Town explores an event of the past, it also addresses issues of systemic and cultural racism we face in the present, humanizing everyone involved. There is no equivocation. The characters who take on the Klan are fighting for nothing less than their own survival and Campbell makes no apologies for those who find themselves on the wrong side of history. Ian Thomas caught up with Campbell by email in May and June of 2021.

Ian Thomas Can you talk about your personal and professional background? Where you’ve lived?

Bill Campbell: I could probably go on forever about that that. The short version would go something like: I self-published a few novels when two of them, Sunshine Patriots and Koontown Killing Kaper found their ways into academia one way or another— a grad student had written part of his PhD dissertation on Sunshine Patriots while Koontown Killing Kaper has been taught in several university classes. I found myself asking, “How can I be good enough for academia but not good enough for a publisher?” Then I figured that there must be other authors and artists in a similar boat, and that’s how I started Rosarium Publishing.

Your new book, The Day the Klan Came to Town, takes place in Carnegie, Pennsylvania, which is part of the Pittsburgh metropolitan area. How did you come to live in Carnegie?

I lived in Carnegie from 1978 to 1988. My mother and I were living in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, where I had a Black teacher, Mrs. Patton, who told my mom to get me out of that school. My mom found St. Luke’s school, so we moved to Carnegie. I lived there until I went off to college.

What is the history of The Day the Klan Came to Town? Sadly, I think the release of a book like this will always be timely, but when did you learn about the underlying story and how did you set about adapting it?

It’s weird, since I grew up in Carnegie and it all went down in front of my childhood church, you’d think I’d have known about this most of my life, but I only found out about it a couple years ago. My brother and I were at my mother’s house Easter 2019 and we were talking about the hidden histories of Pittsburgh and he brought it up to me. A couple months later, I was driving back from TCAF (Toronto Comic Arts Festival) and looping around Carnegie when the main character, Primo Salerno, popped into my head as Bizhan Khodabandeh’s art. So I figured I ought to write the thing.

From there, I tried researching the riot itself. There wasn’t much written about it. What was, though, was written about the Klan’s actions and the government officials’ actions and a play-by-play of the riot. Who all participated was pretty vague. We know that it happened in the Irish Town neighborhood and that “the Irish and others” met the Klan on the streets, but we also know people all around town were collecting coal, collecting fencing, and ripping cobblestones out of the street to defend themselves. So I had to go to census data to find out roughly who lived in town and kind of guess who the “others” were. My wife’s cousin and the Historical Society of Carnegie helped a lot with that stuff. I wound up driving up there a few times to visit them and to take pictures of the town and find old photographs to help Bizhan.

Then, because Primo decided he was the main character, I read as much as I could about Sicily and Italy and the Sicilian-American immigration experience. My father’s an immigrant, so for more reason than one, I felt sympathy for these folks. But he was Jamaican. Since it wasn’t my story, I knew I’d get some things wrong, but I tried as hard as I could to get it as right as I possibly could.

Even though it is based in fact, you took some liberties in constructing the narrative, since information on this event was hard to come by. I feel like it lends the story an air of allegory. From a story perspective, do you think it was beneficial that you had to connect a lot of dots? Switching gears and thinking of it from an historian’s perspective, how does it make you feel that this event was so unknown?

Really good question. I think being the son of an immigrant myself and being from Carnegie, some of the dots were easier to connect. I think also being Black helped making those connections easier. I think a lot of White writers would’ve had a tough time wrapping their heads around the fact that their grandparents, aunts, and uncles, were targets of the Klan and that the Klan was using the same language for them that they were basically using for Black people.

I wouldn’t really consider myself an historian—more a history buff. However, this riot being unknown has given me a lot of thought. This should be an anti-racism celebration. Hell, why not have parades? But having grown up there, it made me realize that for a lot of people, racism in itself wasn’t bad; racism against them was. Also, once you’re admitted to a club, you want to pretend that you’ve always been a member.

Was part of the draw to this story that Carnegie was not historically known as an epicenter for violent racism? In your research, did you find ways that this racism has persisted over the years? Could something like this happen in Carnegie or a town like Carnegie today?

Definitely. I had no idea that this happened, and I definitely wouldn’t have imagined that something like this could happen in Carnegie, of all places. Of course, once you become more familiar with the racial history of this country, it makes more sense.

Racist violence happens every day in America in all kinds of forms—from street violence to more institutionalized forms. So, I guess the challenge would be finding ways how it has not persisted over the years.

I actually wouldn’t be surprised, as the demographics in this country continue to shift and the US becomes a majority-minority country, if more and more incidents like what happened a century ago in my hometown don’t happen quite often. I think the next several decades are going to be turbulent ones. January 6th was definitely not a one-off.

Do you think people are invested in willfully misunderstanding the difference between xenophobia and outright racism?

Most definitely. As an outsider looking in, people seem to be terribly invested in Whiteness. I mean, the Civil War happened. January 6th happened. People live and die, maim and murder over it. So, there must be something to it, right? So, I’m thinking, for a White person today to admit that what happened a century ago in Carnegie was racism calls into question their White identity (which, I know, can be a loaded term). And for all of us, nothing is more precious than our identity.

Are there limits to how much an acknowledgement of systemic racism would benefit the social order, for lack of a better term? With regard to the myriad problems generated by racism, do you think a cultural shift in attitudes would go further than systemic, legislative changes?

People can admit all sorts of things if there is no personal cost to it. The admission would simply be a step and a relatively minor one. Systemic change is what really matters. When it really comes down to it, how much am I going to care if someone likes me or not if they can legally discriminate against me? Substantive punishment for wrongdoing would probably do more to change attitudes than any kind of social mixers ever could.

On the subject of genre, do you think The Day the Klan Came to Town slots into any existing category? What works do you hope this release can stand beside?

It’s historical fiction. I’m not sure if that’s a category in comics. Is it? In all honesty, when I originally conceived of the story, I figured it would be relevant. January 6th made it even more so. I think it can basically stand by any of the other comics that speak to what’s going on today. Hell, back in January, we probably could’ve sold it next to the New York Times and Washington Post.

Historian and Science Fiction writer Phenderson Djeli Clark introduces his foreword to The Day the Klan Came to Town with two quotes.

The first, from philosopher Karl Popper states: “Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them.”

The second, attributed to Hip-Hop duo Gang Starr, states : “cos now we got chromes to put them where they belong.”

I think this pair of quotes get at the tone of the book, but would like to know how succinct a summation you think they are. Do you think in dealing with the subject of the militant anti-racism espoused in the book the media is willfully obtuse? Do you think that is changing at all, for better or worse?

While I generally hate to use the word “privilege” lately, I think that is what we are seeing in action here every day. There has been a growing storm of White supremacist hatred going on in this country for decades that have gone largely ignored. Part of this is because, to be honest, our government and White supremacy have always had a very interesting relationship, and the other is that the amount of privilege one has dictates the amount of space one has to avoid any threat.

The thing that’s most infuriating at this current moment is that January 6th has already happened. We’ve seen the threat these people pose and the threat they directly pose to the people in charge. You’d think that the press and those in power would remember the lynch mobs roaming the halls of Congress and be fervently anti-racist at the moment, especially since history tells us that this isn’t a one-off and it will probably be worse next time. So, you really have to wonder how strong that interesting relationship truly is and if it’s something that will only grow stronger or will finally be smashed by the changing demographics that make the threat of White supremacy probably the most dangerous its been in our lifetimes.

I definitely think Phenderson captured the heart of the book much better than I ever could.

The truth of the matter is that what’s currently going on has been fairly readily apparent since 2010 and has been way too obvious since this past January. History tells us where this is all going. Yet, when it comes down to it, whatever space is available to avoid a fight, most people will take, and if they can fob that fight off to someone else altogether, all the better (which may very well be where the very idea of “tolerance” stems from).

There will also be elements, even among the sympathetic, who deep down know that they’ll be safe either way. There are even other elements who theoretically want equality but also may fear that they may lose their own status if things were actually equal.

I think, when we’re talking about anti-racism or any struggle for that matter, we have to take all these different factors (and probably many more) into account. Unfortunately, for everybody involved, many of the people in charge fall within these categories, which is why they actually are willfully obtuse. Then, like when Trump was elected, they’ll act surprised when shit goes sideways. But as we’ve seen these past few months, they’ll fall right back into their old ways almost immediately.

Ultimately, it will come down, as it usually does, to the people like those in this book, the ones with their backs against the wall, having to pull cobblestones out of the street to defend their very lives. So, it’s hard for me to look at these things as “better or worse.” We’ll only know when the time comes—when we get to see who actually shows up.

What role do you want your book to play in this conversation?

I’ve never fancied myself a guy with all the answers or any answers, to be honest. But I do have a whole bunch of questions. To me, I hope that Klan is the kind of book that has people questioning the history that they’ve been taught and their place in it and the roles they can play in our country’s future.

For example, even at this point, I’ve seen racists admit that race is a social construct. But here we get to see that the current American construct of race isn’t very old at all (adopted in 1946, if I remember correctly). If race is truly that malleable, what is it that we’re fighting over exactly? And also, if it is that malleable, why does America still discriminate against Black people? After all, we were here 200 years before the first large waves of European immigrants even arrived.

Can you talk about how you hooked up with Bizhan Khodabandeh for this project?

Bizhan has been a Rosarian for years. John Jennings introduced us back in 2014. We published his The Little Black Fish and digitally published his and James Moffitt’s The Little Red Fish. We’ve been friends for years, and he just seemed the perfect artist for this project. He’s a joy to work with and to be around. I couldn’t have asked for a better partner.

As a publisher yourself, why did you choose to pitch this book to other publishers and what do you think PM Press brings to the release of the book?

We only pitched it to PM. It would’ve only been PM or Rosarium. We thought that PM was probably one of the only publishers who would get what this book was about and wouldn’t want to soften its edges. That, no, this isn’t about xenophobia, etc. It’s about racism and White supremacy, and the Klan went after southern and eastern Europeans because they weren’t White. And no, this wasn’t some Kumbaya moment of brotherhood. These people got together because they were desperate and obviously lessons weren’t learned. However, we can learn lessons from this if we choose to.

That kind of understanding between a publisher and their creatives is invaluable. And PM will literally go to the ends of the Earth with your book. Who can ask for anything more?

Can you talk about the formation of Rosarium Publishing and your role in it? What were your goals in launching Rosarium?

I started Rosarium in 2013. Basically, I was seeing a lot of Brown folks not being published, and I knew a lot of the old excuses simply weren’t valid. My own experiences told me it wasn’t because of lack of quality. Social media was telling me that it wasn’t because an audience didn’t exist for the stuff and it also told me it wasn’t because these artists and authors didn’t exist. So I figured that if I could provide a stepping stone for as many artists as I could, maybe it could help some of them.

Rosarium’s publication roster is very diverse and I imagine it speaks to your own sensibility. Can you talk about your influences and your artistic education? Where and when did you find comics and how have they fit into your life over the years? What titles were you reading?

I fell in love with comics as a kid. My aunt was dating a Vietnam vet who loved them and used to share them with me. The first two comics that really stuck out to me were Uncanny X-men #137— “Phoenix Must Die!” —and Thor #300. I was hooked. I stuck mainly to the superhero stuff when I was in high school. For the longest time, growing up, I thought that was what I was going to do. I went to the Art Institute of Pittsburgh’s teen program to learn how to be an artist. I even did a summer comics program (taught by Tom Grindberg). But around senior year of high school I couldn’t really afford them anymore, then in college my interests shifted to science fiction. It wasn’t until I started Rosarium, meeting folks like John Jennings, Damian Duffy, Keith Miller, and the like, that I really started getting interested in comics again because I was publishing them.

Was that shift to science-fiction in college a reflection of your interests? What authors were you reading? Were you getting something from SF that comics couldn’t provide?

The shift to science fiction really had to do with Samuel R. Delany and Octavia Butler. Butler addressed issues I was interested in, in ways comics simply didn’t do. Delany was so much smarter than I could ever be, I wanted to do what he did. Delany’s Babel-17; Butler’s Wildseed; Zora Neale Hurston’s Moses, Man of the Mountain would probably be the ones that really set me on the path.

What was your thinking in selecting the first titles you brought to market? What was the first publication under the Rosarium banner?

Not to be too glib, but that they were really good and I really liked them. It’s about as simple as that. If I like them, I pass them on to a group of readers I have. If they like them, we publish them. Mothership: Tales from Afrofuturism and Beyond was the first publication.

How has your publication strategy changed with experience?

Small publishing, to me, is an extraordinarily long game. I generally don’t know for years whether something is successful or a failure. It oftentimes takes a really long time for something to catch on for us. So, I really don’t think in those terms. I simply try to come out with the best books I possibly can. That’s the mission here.

What are your plans for Rosarium in the coming months and years?

Things have gotten incredibly interesting with Rosarium. We slowed to a crawl during the pandemic. I was hesitant to release books, not necessarily knowing where they were going (though I’ll admit, 2020 wasn’t too bad, sales-wise). However, last year, we started working with Graphic Audio and RB Media to produce multi-cast audio books with the former. They recently released John Jennings’s Blue Hand Mojo, which is utterly fantastic. They’re currently working on my own Koontown Killing Kaper, Lisa Bradley’s Exile, and Jennings and Ayize Jama-Everett’s Box of Bones. And Storied Media Group is now representing us in Hollywood. We’ve already sold one option, but we’re not allowed to really talk about it yet. So, it looks like we’re branching out and ramping up.

In the meantime, next year we’ll be releasing a collection of short stories by Alex Smith, Arkdust, and two comics projects, Gender Studies by Ajuan Mance and Suzy Samson by Anthony Summey. We also have SFF projects coming up from Dilman Dila and Subodhana Wijeyeratne, and Louis Netter and I are working on a voodoo western graphic novel called Refuge. I’m drawing up contracts on a few other contracts right now. So, stay tuned!