An Interview with the Authors of Black Metal Rainbows

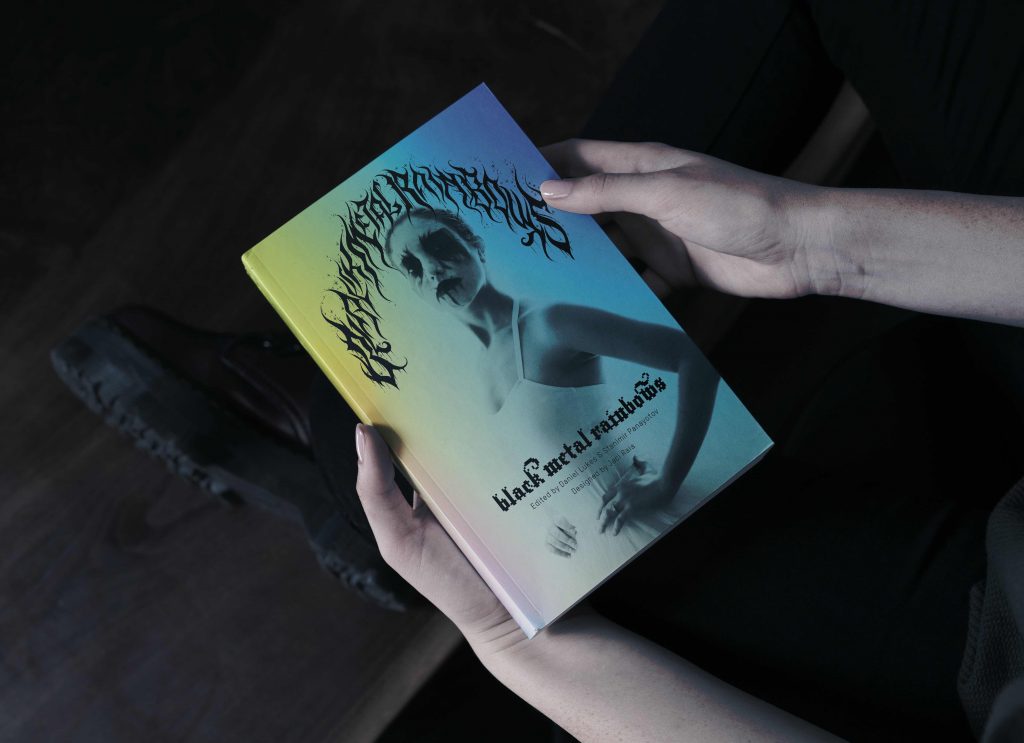

Many of us associate black metal with the Northern European right-wing scene from the 90s and a couple of murders. This book is here to break this semiotic chain and to bring out all the colors of the rainbow that flow within black metal. Edited by two academics and designed by an artist, Black Metal Rainbows is a book that will appeal to hard-core fans and metal newbies alike.

In this interview, the team behind the book speaks more about their project and tells us why Black Metal is for everyone.

(An abridged version of this interview was originally published in the Bulgarian queer zine Out.bg)

Konstantin Georgiev: I wanted to start with the very broad question of what sparked the ideas behind this book?

Daniel Lukes: The book comes from a conference called “Coloring the Black” that I organized in 2015 with Michael O’Rourke, who’s one of the early figures in the black metal theory scene. Drew Daniel, who has been a very inspiring figure to this project, also participated in it. He’s one half of Matmos, he has worked with Björk on two of her albums, Vespertine and Medúlla, and he’s also an academic. He also has this side project, The Soft Pink Truth, which has an album Why Do the Heathen Rage?, which is a sort of queer disco electronic industrial reworking of black metal. We had the conference in 2015 and there was a lot of backlash against it: a lot of people who were just sending death threats and doing all sorts of trolling.

Two themes of “Coloring the Black” have carried over to this book. One of them is the rainbow and the colors within black metal, and then the other is opening up the genre from the perspective of gender and queer theory. That hadn’t been addressed much by the original black metal theory group, whose vision of what black metal theory should be was something we were rebelling against somewhat. To them, black metal was very much about Romantic philosophy, very Nietzschean and taking at face value a lot of ideas that some black metal has about itself.

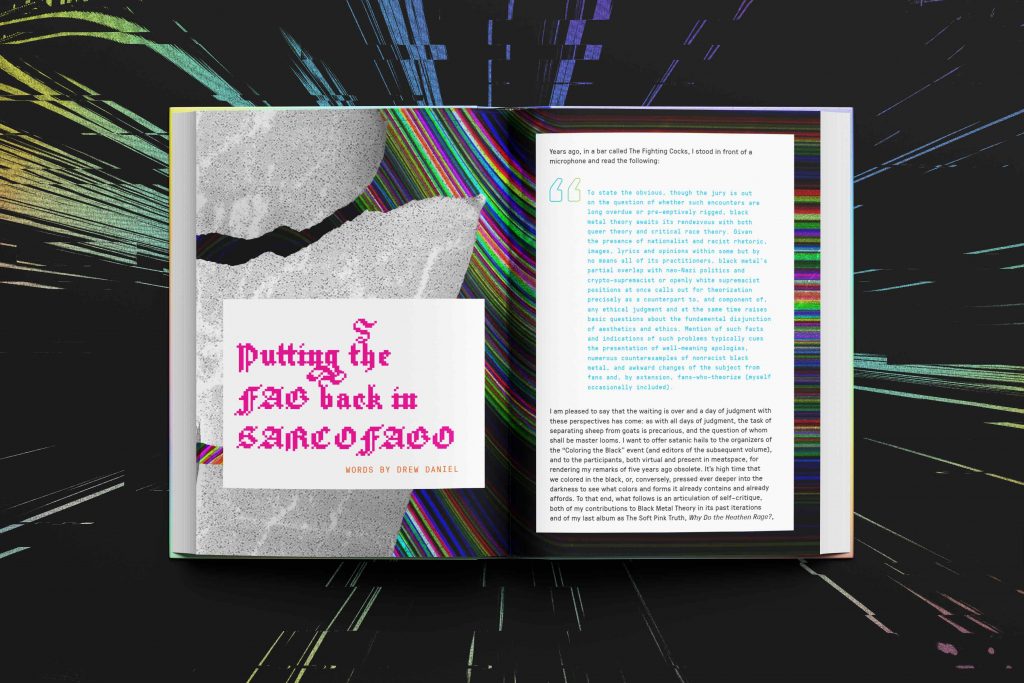

Jaci Raia: In a lot of ways this is my dream project. When I was in college, I had to come up with an idea for my senior thesis, and the professor who guided me suggested that I design something that could potentially help me land a job. I desperately wanted to get a job designing books, so I wrote, designed, printed and hand-bound a book about the underground metal scene. Cut to 15 years later — my thesis book sadly never landed me a job in publishing, but here I am finally designing a book about music and culture. Longform projects have always been immensely appealing to me, as they require you to do a deep dive into a subject, and then create a compelling visual system for the design that speaks to the content. Black Metal Rainbows is a perfect combination of my two lifetime love affairs: metal music and design. Life really does find a way.

Konstantin Georgiev: Tell us more about what’s inside the book — it started from a conference, but it’s not exactly an academic book.

Daniel Lukes: It has its academic elements, but some of the texts are just very much on the other side of writing, whether it be journalism, personal essays, or manifestos. One of the main problems with the initial black metal theory is that it was often densely postmodernist critical theory. It was a sort of a club. While we wanted to speak to the scholars of cultural studies and metal and so forth, we also want to speak to the fans. We want black metal fans to get this book, and even people who only have a vague idea of black metal.

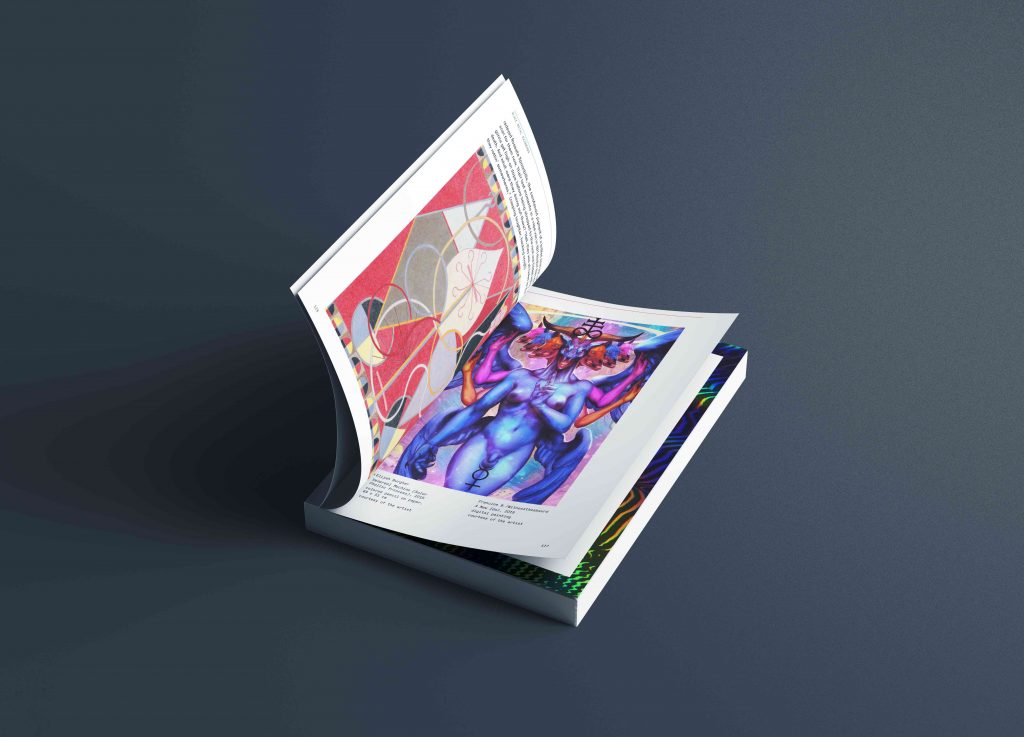

It was also very much important for us to let this be an art book. So the book is full of artworks and that’s why Jaci Raia, as a designer, is a full co-author of the book with the two of us. In a way, the book doesn’t simply tell, but also shows the multiplicity and the diversity of black metal.

Stanimir Panayotov: We also include many other artists and it has been a really interesting process to find all those super cool artists to include in the book. Of course, we didn’t get everyone we wanted because sometimes you hit somebody who you think will be super happy to join, but they never answer. We’ve managed to include quite a lot of established artists, but also quite a lot of emerging ones who are just starting their careers, but are very, very promising. And we’ve tried not to think about it and let the visual side of things lead the narrative too.

Konstantin Georgiev: To me, all those things make it sound as if this book would be quite difficult to put together and design. Jaci, did this book differ a lot from other projects you’ve worked on?

Jaci Raia: It did, and it didn’t. A majority of my freelance work is for friends who happen to be into metal. I’ve done tape designs, tons of logos, vinyl album artwork, site graphics. The remainder couldn’t be more different — I think it’s imperative as a designer to be able to adapt to the project at hand regardless of what your personal tastes are. I’ve done brand identities for a skincare startup, a wealth management firm, and a rockabilly knitting company. I’ve done a coffee table book to showcase scenic photography of Bald Head Island, NC and I’m currently working on the identity and interior for a restaurant in Burlington, VT. This is all, of course, after quittin’ time at my job in advertising. Most day jobs aren’t glamorous, but if you do it right, they will allow you the time to do passion project stuff on the side. That’s how I retain my shred of sanity.

Konstantin Georgiev: Going back to something Daniel said earlier about this Romantic Nietzschean idea that comes with black metal. In many people’s minds black metal is the black metal of the 90s, with its satanic scandals and the murders, and all that. So I’m curious how do you go about queering this history and where does queer fit in?

Stanimir Panayotov: What you’re talking about is the second wave of black metal from the 90s. So the reason why people know black metal is because of the satanic scandals, that’s how it became a global phenomenon. But this is not the entirety of black metal. Black metal has a more complicated and more picturesque history from Venom onwards, so if you want to be rigorous about the way you approach queering black metal, you should really start from the beginning. Not from the middle ground. But usually people will pick up the middle ground and start with the second wave, as if it’s the first one. And it’s not that people forget it — most people know that. It just happens by popular demand, so to speak.

We also have to note that the idea of queering is a little bit of a retrospective and in that sense queering is a bit misleading, because what we’re doing is trying to showcase the history of how queer it has always been. Of course queering is a thing that we do, but it’s building up on a history of queerness that is already out there and so in the book we’re trying to strike a balance between the two.

Daniel Lukes: That’s a very interesting point because some people might say, and they have already said, “How dare you bring this stuff to black metal?” But I think one of the things we’re trying to show is that this was always there. The queerness was always within black metal. The rainbow was always within black metal. So we’re not doing anything new per se, we’re just kind of shining a light on something which was always there. Certain factions had a vested interest in emphasizing the other parts of the genre: the warrior, the grim and frostbitten kingdoms and all of that. But there’s always been this sort of shining rainbow that the reputation of black metal has shrouded in darkness. So part of what we want to do is bring it out and yes, there’s also a kind of pleasure involved in that. The popular image of black metal is one thing, but I think it’s fun to show how in fact there’s a lot more to the story.

Konstantin Georgiev: Hearing you speak about this kaleidoscopic book and thinking about what you said earlier — that this book should be accessible to scholars, fans, and newcomers alike — I’m curious to ask how hard was it to design the book with such a diverse audience in mind?

Jaci Raia: Honestly, it wasn’t that hard. I fully stand behind their mission to make the book accessible, which is why it doesn’t fall victim to a lot of the visual clichés one might expect when working with black metal content. Had it been real lo-fi, black & white, gritty, and vaguely oppressive, it might have seemed too exclusive and closed off to anyone who isn’t already into this kind of shit. Giving the book it’s own unique aesthetic goes a long way into helping it appeal to a wide range of folks. Plus, it’s just a personal mission of mine never to design anything that looks typically “metal.” I hate that aesthetic with every cell in my being.

Daniel and Stanimir also were both adamant that the book be dazzlingly colorful yet chaotic, to echo the content, contributors, and music. I was able to create a visual language that balanced the beautiful swirling chaos and made sure the writing and artwork were at the forefront of the book design. It’s important that the content is clear and legible. I know it sounds counterintuitive to admit as a designer, but I’ve got a bunch of books that favor form over function, and I loathe them. I subscribe to Beatrice Warde’s Crystal Goblet approach — she wrote an essay explaining that typography should never detract from the actual content, much like a wine glass should never obscure the experience of drinking the wine. Preach.

Lastly — the choice to really dial up the saturated colors, vibrant rainbows and lots of pink in the book design is a lowkey “fuck you” to those who would like to keep black metal as walled off and unaccepting as possible. Black metal is for everyone.

Konstantin Georgiev: Since we’re already talking about bright colors, let’s talk about the rainbow then. When I was reading the book’s introduction, I really appreciated how it’s structured around the different colors that can fit within that history. And I was really into this phrase you have, that black metal can be seen as an ecology of ideas. Could you give some examples of this diversity?

Daniel Lukes: My original idea for the introduction was to have a black metal rainbow where we would indeed have a separate section for each color. Unfortunately, in the end that didn’t fully work out because it just became too long. One color we didn’t get enough of a chance to explore is blue, you know how all rock comes from the blues, and how central the blues are also to black metal, in a sense — having the blues, feeling blue. The blues are very much about feeling down, or, melancholic about the state of the world, maybe because you’re in love with someone. And where does love go in black metal? Black metal is in a sense a world that tries to pretend that love doesn’t exist, only hate does. But love has to go somewhere and in black metal love ends up going in some quite very weird and dark places: the love of violence or nationalism, which is a horrible distortion of what love can be.

Another thing is that blues is very much a black music, so one of our concerns was to think metal from a racial perspective, so you have the Blackness of black metal, and the Blackness of Black people that is somehow erased by black metal’s performance of whiteness. There’s great essay in our book on Zeal & Ardor, written by Laina Dawes, which rejects this Varg Vikernes attempt to obscure the African roots of blues and rock music and I think it’s important to bring that history back out into the conversation again.

Stanimir Panayotov: Two things regarding color. First, the whole idea of the spectrum was important because the rainbow is a spectrum, right? So it includes various colors. But a spectrum can be reduced to a single color too. There will be people who’d want this book to be about the spectrum of blackness in and of itself. Think of sending off your book to the printer: if your cover is black, they always ask you what kind of black you want.

The other thing is that the book is also a spectrum in the sense that it’s been continuously enriched from the moment we started off until now. The richness of black metal five years ago wasn’t what it is now, so as you work on the book, you also have to be aware of how this ecology of ideas evolves. I don’t know if you follow this band Ulver. They are a band that started off as a typical black metal band in Norway from the early 90s, and for me personally, they are almost a textbook example of how rich black metal can be. It started off from typical black metal sounds and now it can be almost drone and ambient. In their lyrics they discuss so many different topics that I personally find it almost inexhaustible to discuss.

Daniel Lukes: I grew up in the 90s too and for me the 90s were sort of the golden age of everything. However, Svein Egil Hatlevik, one of the guys we interviewed, says that the golden age of pluralistic black metal is now, and I think there’s a lot of wisdom to that. There was a lot of creativity in the 90s, but then in the 2000s metal became very conservative. Now I think black metal is opening up again — it can be pop, it can be industrial, it can be electronica, it can be shoegaze anything you want. This sort of strict division between scenes is waning at large and I think that also applies to queerness and metal. You can be queer, you can be trans and it can be part of your artistic identity as well, it’s not just something you happen to be, but it’s something which informs your outlook and aesthetic. Now you have projects like Feminazgûl, Vile Creature, Liturgy, Body Void that maybe couldn’t have really existed in the same way ten or twenty years ago.

Stanimir Panayotov: And just one final thing on the ecology, you [Konstantin] and I come from the same country. I don’t know what your memories are, but you know the so called metal shops in Bulgaria. They are this phenomenon from the 90s and to this very day when you go into a metal shop in Bulgaria it’s this complete ideological hodgepodge where you go and you see on the very same wall all the patches and the pins that they’re selling and it includes the entire ideological spectrum, from Nazis to antifa and it’s so confusing. If somebody from the Western Europe goes into a Bulgarian metal shop, they will be completely aghast with the ideological indifference of commercialism. But people in metal shops are like, “Yeah, you should include everybody”. And it’s a phenomenon from the 90s that still carries on.

Konstantin Georgiev: In a way, this can apply to queerness too, since it can have all those other identities folded into it. There’s this line in the introduction that, in my mind at least, equally applies to black metal and to identity politics more broadly. You write that “Black metal rainbows include and affirm every difference because it is in difference that we are created as identities”.

Daniel Lukes: So I’m looking at it and it goes on, “And since everyone is invited over this black metal rainbow, nobody is invited too.” I think one of the key messages of the book is that black metal is open to anyone and everyone. There are some people that would like black metal to be an exclusive club, but part of our point is that the music is available to anybody in a sense. I think our book repeatedly makes the point that black metal is too good to let Nazis have it. You know, they try to appropriate it, but there’s no reason to let them have it. Often people don’t know much about black metal, but they may have heard that it’s full of Nazis, so they’re just like “You know, forget it, I don’t even want to deal with it.” I think our project, in a sense, is a rejection of that and saying “No, they don’t deserve to get it.” In fact, they deserve to be kicked out of black metal because they are the ones who refuse to let everyone else in.

___

Konstantin Georgiev is PhD candidate at the Department of Anthropology, Rice University, and has written and researched script for film and TV documentaries.