By A. Iwasa

Trial and Error Collective

May 20th, 2021

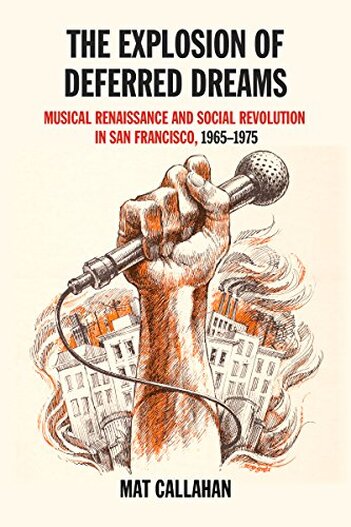

In The Explosion of Deferred Dreams, author, musician, and native San Franciscan Mat Callahan offers a critical re-examination of the interwoven political and musical happenings in San Francisco in the Sixties. Using dozens of original interviews, primary sources, and personal experiences, the author shows how the intense interplay of artistic and political movements put San Francisco, briefly, in the forefront of a worldwide revolutionary upsurge.

Born and raised in San Francisco, author Mat Callahan grew up in a house where his mother played rock ‘n’ roll like Bill Haley and Ray Charles, older and newer folk music from Pete Seeger to Joan Baez, and was playing a great deal of Bob Dylan when the British Invasion started. Meanwhile Callahan was a junior high surfer. This was a pivotal moment, when he decided to pick up the guitar.

Shortly afterwards, Callahan’s father, who opposed him becoming a guitarist, woke him up at 4AM to witness the police arresting hundreds of students at University of California Berkeley. This was during the Free Speech Movement, and Callahan’s father was longshoreman where the International Longshoremen’s Warehousemen’s Union had strong, radical roots going back to the 1934 general strike, and both of his parent’s were part of that tradition: straight up Communists!

After brief acknowledgments outlining the creative process of the book, Callahan makes a personal introduction, laying out the connections of Bay Area arts and radicalism, where his mother was a dancer and his sister had participated in the protests against the House UnAmerican Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1960.

But make no mistake! This isn’t just another self-congratulatory New Leftist’s reflections. Nor some Neocon’s account of why he went right wing. This is a critical examination of the promise of radical arts and politics of the 1968 youth, with passing references to movements from Mexico City to Paris, and Shanghai to Prague, and why those promises continue to go largely unfulfilled.

In his Foreword, Callahan deepens his philosophical analysis and further explains how it relates to the research for the book.

The chapters in turn look to answer the questions and argue the points made initially, starting with an examination of how San Francisco became such a well-known, creative hub. The depth of the city’s importance as a port town is argued back to its quick growth as a Gold Rush boom town.

Later but still far pre-1960s literary heroes like Jack London, Ambrose Bierce and Mark Twain’s writings about SF albeit minus the literary movement aspect of the Beats.

I was particularly tuned in to all this. I was born in the Bay Area, and have spent some years there as an adult. Even so, I’ve long believed cities like Cleveland, Ohio (Clevo) are just as culturally productive, but through a combination of forces both great and small end up seeming like one-horse towns compared to hubs like SF.

At the same time, I am a huge fan of a great number of Bay Area, and Bay Area-connected writers and musicians both past and present, so I really wanted to see all the points in this book argued out, and compare them to my knowledge and understanding of the other hubs and places often unfairly considered fly-over country.

Callahan goes on to really hit his stride with an examination of the inherent feminism of Modern Dance with San Franciscan Isadora Duncan, and the 1916 Preparedness Day Parade bombing as pretexts for things to come in Bay Area arts and radicalism.

After working his way to Kenneth Rexroth, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, City Lights Books and some of the Beats associated with the Bay Area, Callahan backtracks to the massive influx of southern folks both white and Black during the Great Migration. There were deep cultural influences on the Bay Area by such a huge demographic change. In fact, this was part of the largest internal migration in US history. This in turn led to the Civil Rights Movement in the Bay Area, and was a precursor to the massive migration of white youth around 1967, deeply associated with that era.

Also as a sign of things to come, Callahan writes about a 1964 Dakota Sioux occupation of Alcatraz Island, testing the Sioux Treaty of 1868, and in turn bringing attention to the over 600 treaties the United States had broken with Native Americans.

Callahan connects Beat poetry and comedy in discussing the obscenity trials of Lenny Bruce and Allen Ginsberg which both happened in the Bay Area. I often wonder how many punx and hip hop kids in the US take their free speech for granted. Stories like this alongside Jim Morrison of The Doors are crucial in understanding free speech in US American arts.

The influence of the Old Left, primarily the Communist Party, is emphasized in Callahan’s description of the New Left and ’60s Bay Area arts in a way I’ve rarely seen outside of literature on Students for a Democratic Society.

Similarly, Rock ‘n’ Roll’s evolution from race music and rhythm and blues as 1940s Black and urban music, to the music of a generation of teenagers, only recently being cultivated as a demographic by the burgeoning entertainment industry is examined. The simultaneous folk music revival is also written about, specifically Pete Seeger’s band, The Weavers, who sold over four million records between 1950-’52.

The next wave of folk musicians such as Joan Baez and Phil Ochs bring back the book’s connection between new music and social upheaval.

Afterwards, Callahan describes counterculture as coming from subculture: a convergence of Bohemian, juvenile delinquent and Black culture. Tightening up the political aspect again, he uses “Strange Fruit” by Billie Holiday as an example. An anti-lynching song written by a Communist, Abel Meeropol (AKA Lewis Allen) for instance, “Strange Fruit” remains well known.

Returning to San Francisco in the ’60s, Callahan starts digging into the specifics: how song format started to break molds like three-minute time limits, and the innovative incorporation of other artistic disciplines such as dance and graphic arts. The local influence of the San Francisco Mime Troupe and Teatro Campesino are given as examples of theater’s influence.

Mat Callahan really, finally, brings it all together when writing about the 1965 opening of the North Beach, SF venue, Mother’s. It was the first club in the city to have a light show, which was done by the theater group the Committee’s Del Close. Grace Slick’s band before Jefferson Airplane, The Great Society, was also produced by Sly Stone! It was possibly the world’s first psychedelic club.

Sly Stone

The Matrix is another club written about as a pivotal predecessor to the Filmore and the Avalon, both of which would be legendary later. Recording the history of clubs like Mother’s and the Matrix are one of the main reasons I track down books like this. Though the Matrix was much longer lived than Mother’s and it’s where Jefferson Airplane played their first gig, its reputation has somehow not registered in my studies of the era.

Again here, Callahan is really hitting a stride with the specifics. Airplane, the clubs they played, the people who put on the shows like the Family Dog: there was a perfect combination of time, place, creative energies and vision.

LSD, which was still legal in 1965, the Merry Pranksters and the Grateful Dead enter the narrative. Callahan stresses the experimental nature of things. Not just musically or chemically, but with how shows were structured to be something bigger than just a concert.

Callahan’s writing continues to be all over the place for the most part. Criticizing the racist and exploitative nature of the music industry, he goes all the way back to its emergence after the US Civil War and minstrel shows to prove his point. I understand the desire of some writers to break from linear structures to stress ideas over time lines, but it comes off as a bit frantic in this book.

Using the division between musicians and the music industry as an example of the difference between being authentic or not, Callahan eventually works back to the 1960s Bay Area, this time highlighting the South Bay folk scene that spawned Jerry Garcia, Jorma Kaukonen, Paul Kanter and others.

Reading the origin stories of so many bands that remain world famous is interesting, but the clincher for me is that Callahan doesn’t neglect the other musicians, writers and other kinds of artists that made the scene so fertile. Some musicians and bands were new to me, others I recognized their music from oldies stations but I never knew their names.

Callahan goes on to write about some of the local underground newspapers such as The Movement, which is new to me, and the San Francisco Oracle, The Berkeley Barb, and the Underground Press Syndicate it was a part of. The UPS was made up of five newspapers with a readership of about 50,000 in 1966, growing to 200 newspapers with some six million readers by the summer of 1970. There was also a Liberation News Service sending out memos to over 400 media outlets by 1970, and of course The Black Panther whose circulation was 30,000 copies a week by March 1969.

What led up to the infamous gatherings such as the Human Be-In and the Monterey Pop Festival is described, not just the events. As usual, major events were preceded by many minor ones.

Here again, I feel like Callahan hits a certain stride, specifically with getting into some of the philosophical underpinnings of the San Francisco Mime Troupe splinter group, The Diggers. I also feel compelled to change my review style here from an account to more philosophical (I’m not cheating to meet a deadline like I did once for Slingshot. I’m not even operating on a deadline!). If you’re looking for a book to nerd out to creative processes or celebrity gossip, this book probably isn’t for you. But if you’re interested in understanding the socioeconomic and ideological currents that made the 1960s and ’70s San Francisco Bay Area both a creative hub and a powder keg, this book is a gem.

But perhaps what I find the most promising about it is how it can serve as a model for both music writers and researchers of culture in general who want to understand how life influences art in broader terms than usual, and vice versa in a specific time and place.