By Henry Reichman

AAUP

May 2nd, 2021

After four horrifying years of the Trump administration’s nonstop assault on public education, science, expertise, and even truth itself, it is easy to forget that many of the educational policies and practices promoted by the forty-fifth president and his minions were in critical respects little more than extreme variants of corporatist and neoliberal strategies that had too often gained depressingly bipartisan backing under previous administrations. While there is reason for optimism that the Biden administration has learned from that disastrous consensus, it should not be forgotten that one of this century’s most sustained and dangerous assaults on public higher education took place not under Trump and not in a red state but in one of the country’s most progressive cities in its most lopsidedly Democratic state.

City College of San Francisco’s five-year battle against an arguably rogue accrediting agency was possibly the most critical struggle waged by higher education faculty during the Obama years. It began in 2012, when the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges (ACCJC) placed the college under “show cause,” requiring it to demonstrate why it should remain accredited and not be shut down. Subsequently, the commission found that CCSF’s governance and fiscal management problems were so severe that it had no choice but to revoke accreditation, even though it found no substantive faults in students’ educational achievements or in the quality of instruction. Faculty, students, and community members fought back. Even those who thought CCSF’s problems were genuine, and perhaps serious, concluded that rather than helping the institution improve, ACCJC seemed hell-bent on simply shutting down what was, in 2012, the nation’s largest community college, with more than ninety thousand students.

The fight grew to encompass two faculty union contract campaigns and a one-day faculty strike; two major court cases, including a legal challenge from the San Francisco city attorney that bought CCSF more time in 2014; and a last-minute 2015 deal that gave the college two more years to comply fully with all accrediting standards. Meanwhile, the battle expanded to include a movement in which nearly all of the state’s more than one hundred community colleges declared “no confidence” in ACCJC, vowing to seek a new accreditor. In the end, the nineteen-member commission finally acknowledged in January 2017 that CCSF had fully satisfied all accrediting standards and granted the college a maximum seven-year approval. By then only five of the original commissioners who had sought to revoke CCSF’s accreditation remained. Also gone was ACCJC’s vindictive and obstreperous president, Barbara Beno, whose actions both led to and exacerbated the conflict.

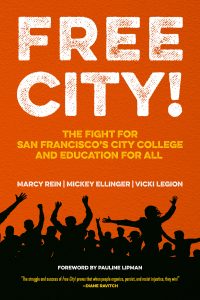

I wrote frequently and at length about the CCSF struggle on Academe Blog, and the AAUP took an early position in support of the college. Now, however, the full and complex story has been told in considerable detail and with great verve in Free City! The authors, two journalists who covered the fight and a faculty member who participated in it, are well situated to provide a coherent and absorbing narrative and, more important, probing and persuasive insights. The story is told in good measure through the words of participants, taken largely from interviews with more than ninety individuals. If the tale comes to something of a happy ending, with the college surviving (despite having lost more than 40 percent of its enrollment), it is hardly an unadorned morality play in which the “bad guys” are permanently defeated by the “good guys”—or, in some cases, the “not-so-bad guys.” Free City! does not pull punches in tackling the inevitable divisions and conflicts that challenged CCSF’s defenders and the broad coalition they built. Nor do the authors shy away from acknowledging the human toll of the struggle for those it mobilized. This is a deeply humane and sometimes touching tale.

Free City! does an excellent job of situating the CCSF struggle in the broader context of the national educational “reform” agenda and its hollow calls for “student success.” Like many other two- and four-year public institutions, CCSF was chronically starved of funding by the state and then charged with “fiscal irresponsibility.” According to ACCJC, the college had too few administrators; its decision-making, in many respects a model of shared governance, was inadequately centralized; and it devoted too many resources to programs that did not yield high transfer rates to four-year institutions, including its much-vaunted ESL program, which served thousands of immigrants, speaking thirty-three different languages, from all over the globe.

When it came to results, of course, the college’s enemies could say little, as evidence of student achievement was overwhelming. Yet because of the absence of elaborate and formal student learning outcomes (SLOs), which the authors rightly describe as “a way to pretend to quantify educational results,” ACCJC could still question the college’s “ability to adapt successfully to the changing resource environment.” Here’s what happened when ACCJC evaluators insisted that SLOs must appear in full and in English on all first-day handouts in ESL classes. “We were used to teaching refugees, nonliterate immigrants, and immigrants with no other resources,” the ESL coordinator recalled. “A list of objectives in a language and writing system totally foreign to many would add more confusion to the already anxiety-filled situation of arriving in a new country. The ACCJC rep told us that ‘students could take the papers home and find someone to translate’ the objectives to them. It was insulting to everyone’s intelligence.”

The attack on CCSF, Free City! argues, was in critical respects an extension of the privatization agenda already devastating much of K–12 public education. Indeed, CCSF activists learned much from the Chicago Teachers Union’s successful 2012 strike, with its extensive community involvement. “In the community colleges,” the authors write, “privatization involves: downsizing public community colleges, which gives for-profit colleges new room to grow; more outsourcing to private contractors; promoting full-time attendance.” That CCSF’s student body was and remains overwhelmingly working class and ethnically diverse—there are, for instance, more Asian Americans at CCSF than at all eight Ivy League universities combined—was central to both the assault on the college and, even more important, to the movement resisting that assault. As one activist student put it, the conflict was about “competing visions.” One vision was that of “a downsized corporate model in which marginalized students are pushed out and this mirrors the gentrification and eviction of diverse communities from San Francisco.” On the other side stood a vision “of community values being restored, enrollment being restored, community college being free again . . . a college that supports the community and lifelong learning.”

The CCSF story is also important because of what it reveals about deficiencies in our national accreditation system. To be sure, ACCJC was in many ways a “rogue” agency, and some of the acrimony surrounding the conflict can be attributed to the spiteful and unyielding Beno. “I have never dealt with a more arrogant, condescending, and dismissive individual,” opined one Republican legislator. When, in 2015, I had the honor of joining more than thirty CCSF supporters to testify against ACCJC at the National Advisory Commission for Institutional Quality and Integrity (NACIQI) meeting in Alexandria, Virginia, I ran into Ralph Wolff, former director of the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, ACCJC’s four-year equivalent. A NACIQI member who had recused himself from discussing and voting on ACCJC’s fate, Wolff was not shy about telling me that he believed the issue was largely a matter of personnel and bad leadership.

He had a point, but as one CCSF activist bemoaned, “You wish it was a rogue agency. It would be a lot easier to deal with.” Free City! does not explore broader concerns about accreditation at much length, nor does it examine—possibly because sources were unavailable—internal tensions and conflicts within ACCJC. In my own testimony before NACIQI I stated:

Recently Secretary of Education Duncan declared that accrediting agencies should be better “watchdogs.” We agree, but at whom and what should they bark? ACCJC would snap at the letter carrier and delivery person but wag their tail at the burglars. The real issue is not the volume of the barking but ACCJC’s failure to challenge institutional priorities and practices that erode genuine educational quality while arbitrarily disciplining institutions for petty or irrelevant “violations.”

To what extent does such behavior characterize other accreditors? Free City! offers no definitive answer, but readers will surely suspect that the evidence is not likely to be encouraging.

In the end, as University of Illinois at Chicago professor Pauline Lipman writes in her foreword, “this is fundamentally a book about organizing.” As such it merits a prominent place on the shelves of those who not only seek to interpret today’s crisis of higher education but also strive to change it. I have rarely encountered a work that describes the painstaking labor of organizing with such clarity and honesty. This was a dauntingly complicated fight, and the organizers needed to learn how to be sensitive to political realities, to overcome legacies of mistrust, and most important to listen carefully to the concerns of those they sought to represent. This goes for both the students and the community activists who bridged multiple fault lines to hold together the Save CCSF Coalition and the faculty members who, in the face of their own divisions, united behind the leadership of their local, AFT 2121, supported by the statewide California Federation of Teachers and the national American Federation of Teachers, which early on recognized the significance of the battle.

The title Free City! conveys a dual meaning. On the one hand, it refers to the fight to free CCSF from the existential threat posed by ACCJC and its “reform” agenda. On the other hand, it refers as well to the movement, growing out of this struggle, to make CCSF tuition-free once again for all San Francisco residents, a movement that won a hard-fought, albeit uncertain victory. That victory was not without costs, as through five years of conflict CCSF lost some twenty-three thousand students, a third of its full-time faculty, nearly a quarter of its for-credit classes, and more than 40 percent of its noncredit classes, mainly ESL sections. And the ACCJC’s cramped vision of community college “student success” survives in such ill-considered initiatives as the state’s Guided Pathways program, promoted by former governor Jerry Brown, which privileges full-time attendance and “on-time graduation,” penalizing part-time students and lifelong learners. Still, CCSF has survived to fight again, and a core of committed organizers has gained invaluable experience and understanding. As one faculty activist put it, “What we won is the chance to rebuild.” There is much to be learned from this excellent and highly readable book.

Henry Reichman is professor emeritus of history at California State University, East Bay, and chair of the AAUP’s Committee A on Academic Freedom and Tenure. He is the author of The Future of Academic Freedom, published in 2019, and Understanding Academic Freedom, to be published in 2021.