By Mark Hurst

Creative Good

April 22nd, 2021

Not long ago, before the pandemic, Bob Ostertag traveled to West Papua, Indonesia. Hundreds of islands there make up the Raja Ampat archipelago, which is known for its scuba diving, as the coral reefs have not yet sustained the bleaching that is so pervasive elsewhere. The hassle of getting to Raja Ampat, the remoteness itself, provides the protection that other places lack.

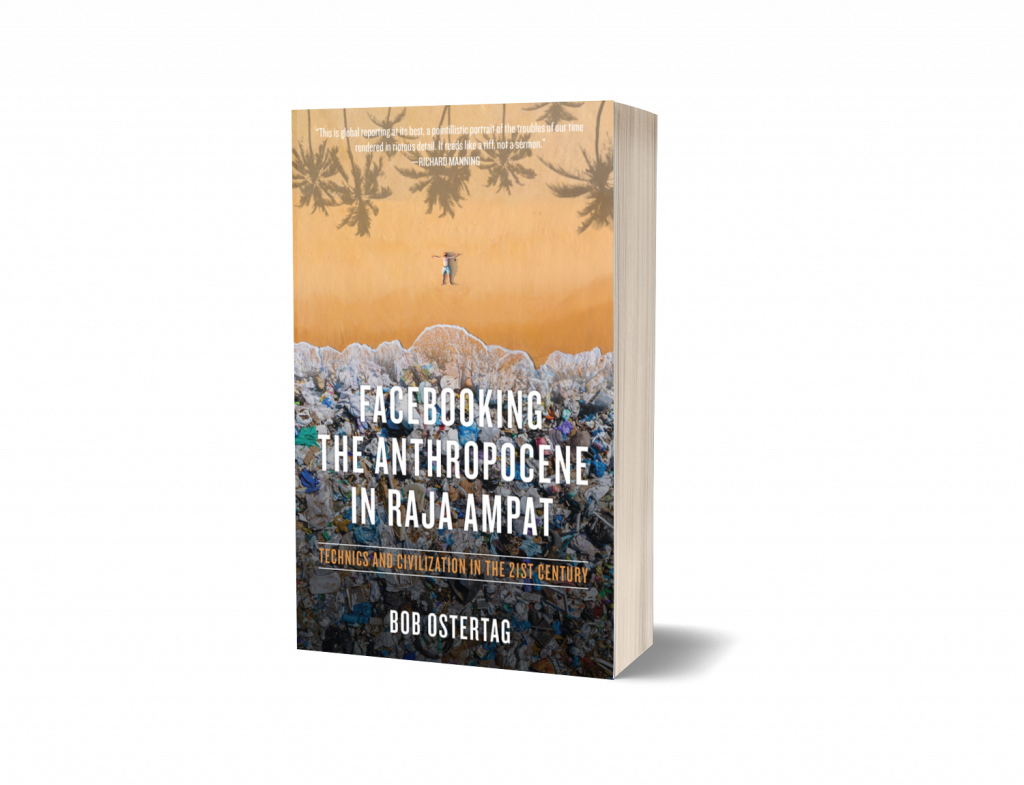

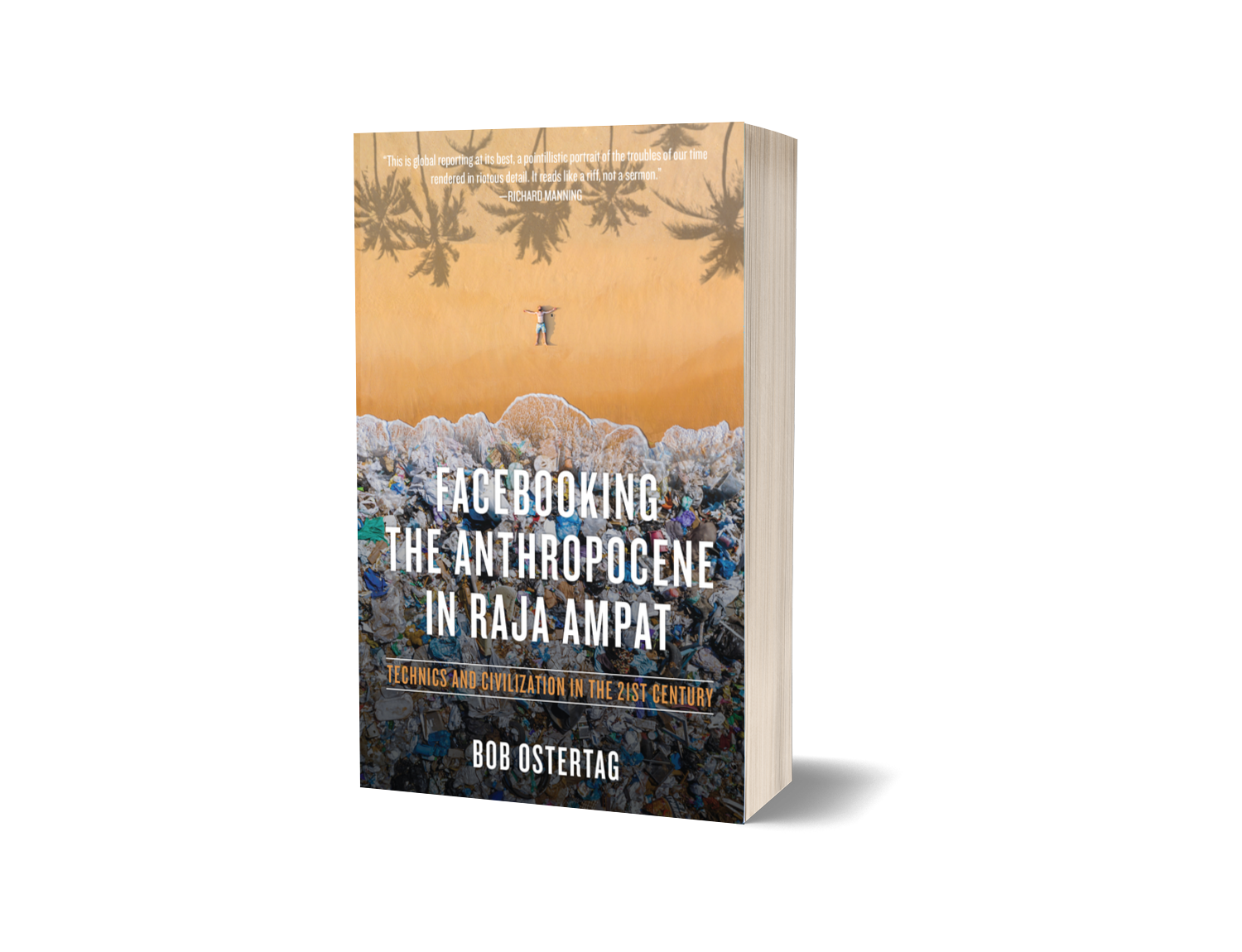

So having taken a plane, then a smaller plane, then a ferry, a motorboat, and finally a kayak, Bob finally made it to what might be the most remote beach in the world. In his new book Facebooking the Anthropocene in Raja Ampat, Bob writes about what he found there:

We camped on the beach of an uninhabited island, a “deserted topical island” fantasy come to life. The quiet. The tropical breeze. Palm trees. Sculpted limestone rock. Plentiful fish. A deserted beach. And garbage.

Lots and lots of garbage. A staggering, mind-numbing amount of garbage. Old flip flops and medicine bottles and soap bottles and shampoo bottles and soft drink bottles and motor oil bottles and aerosol bottles and specimen cups and so on. The beach had a carpet of garbage. [See the book’s cover image. -mh] There was literally no place to put your foot down without stepping on garbage. It covered everything.

Shocked at what he was seeing, Bob decided on the spot that he was going to do something. He set to work, picking up bottles and other pieces of trash, moving them into a pile. But that didn’t last long:

I soon discovered that clearing the plastic from even a tiny little patch of beach was beyond the ability of one person. It was like doing amateur microscale stratigraphy. Intact artifacts like plastic bottles formed the top layer. Clearing that away revealed a layer of fragments of the same artifacts that were intact in the top layer. Excavating layer by layer, the fragments became progressively smaller until they became indistinguishable from the sand. Maybe the sand itself was plastic. Below that would be the plastic fragments even smaller than the sand. Microplastic, it is called. I couldn’t see it because I didn’t have a microscope, but it was there.

I can imagine what that felt like: frustrating to be surrounded by unwanted synthetics, and infuriating to watch helplessly as the stuff continually comes in. Still, Bob reports that some residents of the islands seem to have made their peace with the invasion of trash:

I slept in a bamboo hut decorated with lines of string hanging from an awning over the porch. Knotted in the strings every few inches were beautiful seashells, alternating with colorful bits of plastic garbage and even the occasional rusty aerosol can. The proprietor seemed to make no distinction between seashells and garbage. To him it was all interesting and colorful stuff collected from the environment. Gifts from the sea.

I keep thinking about those Papuan huts, decorated with trash taken from the beach – where more bottles and cans wash ashore every day. It’s not too different from what many people are experiencing, in cities far from Raja Ampat, as their lives are taken over by digital tech. Really, none of us are immune to what’s happening.

It feels more and more like we’ve passed a point of no return, as it’s difficult to imagine any way out of what feels like seismic, irreversible change. The spread of digital technology is central, of course, but also the manufacturing of plastics and other disposables – and supply chains to deliver them all, as I wrote about recently – bringing about a dramatic transformation in the economy and the climate. It’s hard to fit it all into one sentence: apps and algorithms and trash and plastic and billionaires and poverty and cyclones and floods and fires and droughts, all influenced or directly caused by a knotted-up global glop of technology, money, and power. Whatever this thing is, it’s big, and it’s accelerating.

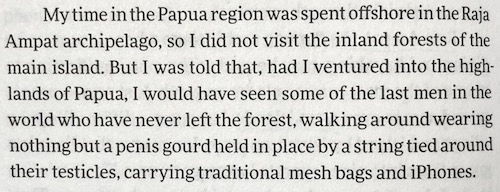

And it’s everywhere. In West Papua, Bob Ostertag witnessed the trash on the beach. But in two well-turned sentences, he describes where else these changes are showing up. (I’ll use an image for this quote since opaque algorithms, out of my control, might not approve of the text version.)

There’s something obscene about that image, the smartphone a jagged discordance to the time-tested human artifacts and practices that it intrudes upon. Thousands of years of isolation, countless generations of tradition, all melted into air. The smartphone knows nothing of history, culture, the land. Instead it can only beckon toward the future: a very particular future, ruled by technology, that looks very much like what Bob saw on the beach.

And carrying a smartphone isn’t just one more device, it’s the entire web (there’s that glop again) that supports it, feeds off of it. When people start getting their wifi from orbiting satellites hurled into the sky by Musk, Bezos, and others, there will be literally no escape on earth from the signal of the machine.

Some people call this “progress.” Some say it’s “inevitable.” I disagree on both counts, but for now all I’d like to suggest is that we acknowledge what’s happening.

I spoke with Bob Ostertag on Techtonic this week and he was, if not always enthusiastic, resolutely nonjudgmental about the accelerating changes in the world. Sure, something is being lost, he said, but that’s different from saying it’s “bad.” The next generation will simply have to fend for itself, as best it can, under the circumstances. (To be fair, that might be what the Papuans above would say about the phones sitting in their mesh bags.)

I strongly recommend listening to the entire interview with Bob Ostertag. But if you only have a few minutes, just listen to Bob’s answer to my final question, asking him whether tech’s upheaval of society doesn’t merit some judgment on our part.

Paul Kingsnorth and West Papua

Coincidentally, West Papua came up on another recent Techtonic, when I interviewed author and “recovering environmentalist” Paul Kingsnorth – another interview I’d strongly recommend listening to. We talked about an experience he had over twenty years ago when his environmental activism brought him to West Papua to spend time with the Lani tribe there. As he describes it in an essay in the Guardian:

Now, as we reached the top of the ridge, a break in the trees opened up and we saw miles of unbroken green mountains rolling away before us to the horizon. It was a breathtaking sight. As I watched, our four guides lined up along the ridge and, facing the mountains, they sang. They sang a song to the forest whose words I didn’t understand, but whose meaning was clear enough. It was a song of thanks; of belonging.

To the Lani, I learned later, the forest lived. This was no metaphor. The place itself, in which their people had lived for millennia, was not an inanimate “environment”, a mere backdrop for human activity. It was part of that activity. It was a great being, and to live as part of it was to be in a constant exchange with it. And so they sang to it; sometimes, it sang back.

Paul has been writing more, recently, about the encroachment of tech on our traditional and human ways of living. He calls it the Great Unsettling, a product of “the Machine.” I wonder whether some of the Lani tribespeople who, years ago, sang to the forest are now looking at screens while they walk.

What is this thing? That’s the first question we have to answer. We need stories, descriptions, names for what’s happening. Because it’s here, it’s big, it’s multifaceted, and it’s accelerating. Some will “make the best of it” and hang up the shiny objects that wash in on the beach. But I think we should examine what these things are, to find out what’s garbage, and what’s gift.

Until next time,

– Mark Hurst

Note to readers: I’m working on launching an online community – a Creative Good membership program – to explore and discuss these issues further. Stay tuned.

Email: [email protected]

Read my non-toxic tech reviews at Good Reports

Listen to my podcast/radio show: techtonic.fm

Subscribe to my email newsletter

Sign up for my to-do list with privacy built in, Good Todo

Twitter: @markhurst