By Paul Buhle

DSA

April 26th, 2021

It is always worth asking why the Industrial Workers of the World, also known as “the Wobblies,” retain an inescapable aura, a century since the organization’s apex and the government repression that laid them low.

There are a few good reasons. The IWW not only organized furiously, from the mining and lumber camps and harvest fields of the West to the grand textile factories of the East. It lifted up the lowest levels of working people and gave them a chance to believe in themselves. It led massive free speech fights in cities that did not want them. Arrested, prisoners filled the city jails, singing their own radical songs!

But there is more to the matter. Wobblies made themselves into superb “soap boxers,” urban lecturers in the day when listening on the street was high entertainment. They were not only eloquent but also funny, best heard in their marvelous, inspiring, and hilarious songs. And they went down bravely, brutalized by cops and vigilantes, sentenced to long prison sentences—sometimes lynched, but always defiant.

The last reason may be the best: They were furiously antiracist because they did not believe in the differentiation of worthy and unworthy workers. By contrast to the haughty American Federation of Labor, whose leader Sam Gompers used the”N word” and blamed the 1919 riots on the Black victims, the Wobs embraced all. Sadly, the successful organization of people of color belonged to another generation, when wartime labor shortages and then the massive civil rights movement moved the needle a bit, if never enough.

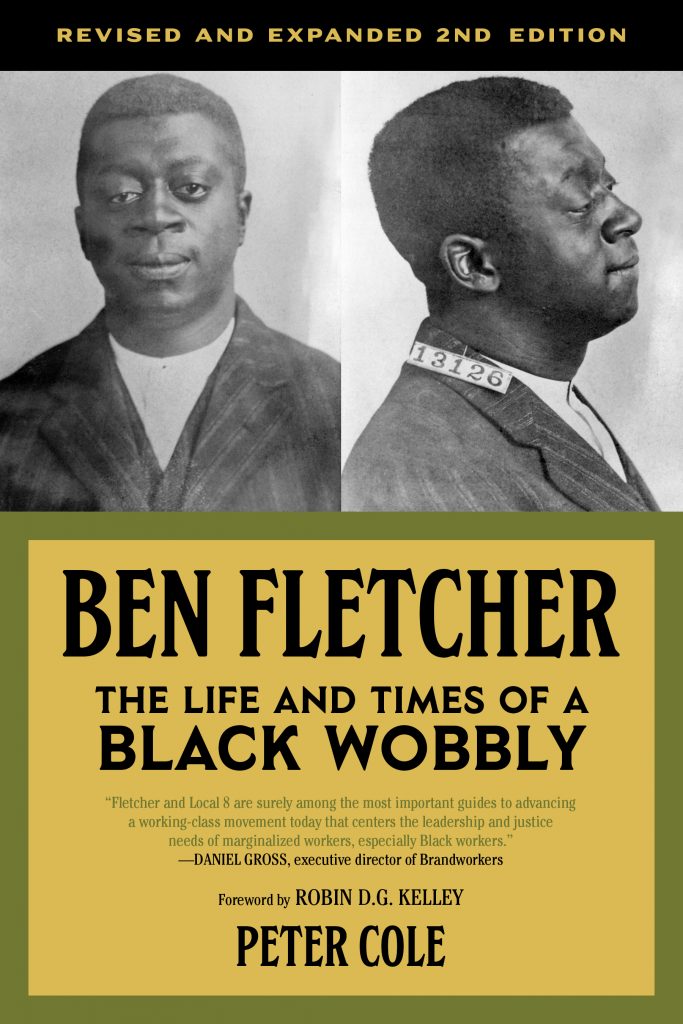

The Ben Fletcher story is, then, a life and a metaphor of the future yet to come. Robin D.G. Kelley’s foreword recalls, from Kelley’s own teenhood, watching the film Reds and wondering, in later years, why so little was made of “The Negro Question” considered central by John Reed himself. Fletcher had been long forgotten, and not only by filmmakers.

Here is the personal saga in brief: Born in Philadelphia in 1890, growing up among ethnic working-class whites, Fletcher entered the world of the longshoremen early on. He seems to have joined both the IWW and the Socialist Party around the age of 20, one of a small but more-than-negligible proportion of African-Americans in either.

Fletcher’s name began to appear in IWW newspapers around 1912, as a speaker at labor rallies. He attended the Wobbly convention in Chicago that year, when the organization called explicitly, for the first time, for outreach to Black workers. For the IWW newspaper Solidarity, he offered shrewd advice about methods of successful organizing.

Leading a strike against all the odds, Philadelphia’s Local 8 won a signal victory in 1913. In true Wobbly fashion, verbal agreements marked the victory, leaving workers the option to go out anytime they felt betrayed. Thousands more joined the Local, proudly wearing their IWW buttons on the docks. Fletcher headed off to Baltimore to organize that port, stopping and speaking in other ports from Norfolk to Boston. If successful, they would have replaced the exclusionary International Longshoremen’s Association with the IWW’s Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union.

It was too much of a climb, with racism at the center of ILA and employer resistance. Fletcher reached out most effectively in places where African-American or Cape Verdean workers had found jobs. After a near-escape from a potentially deadly attack in Norfolk, he relocated to Boston, where the repeal of the miscegenation laws allowed him to marry a white woman.

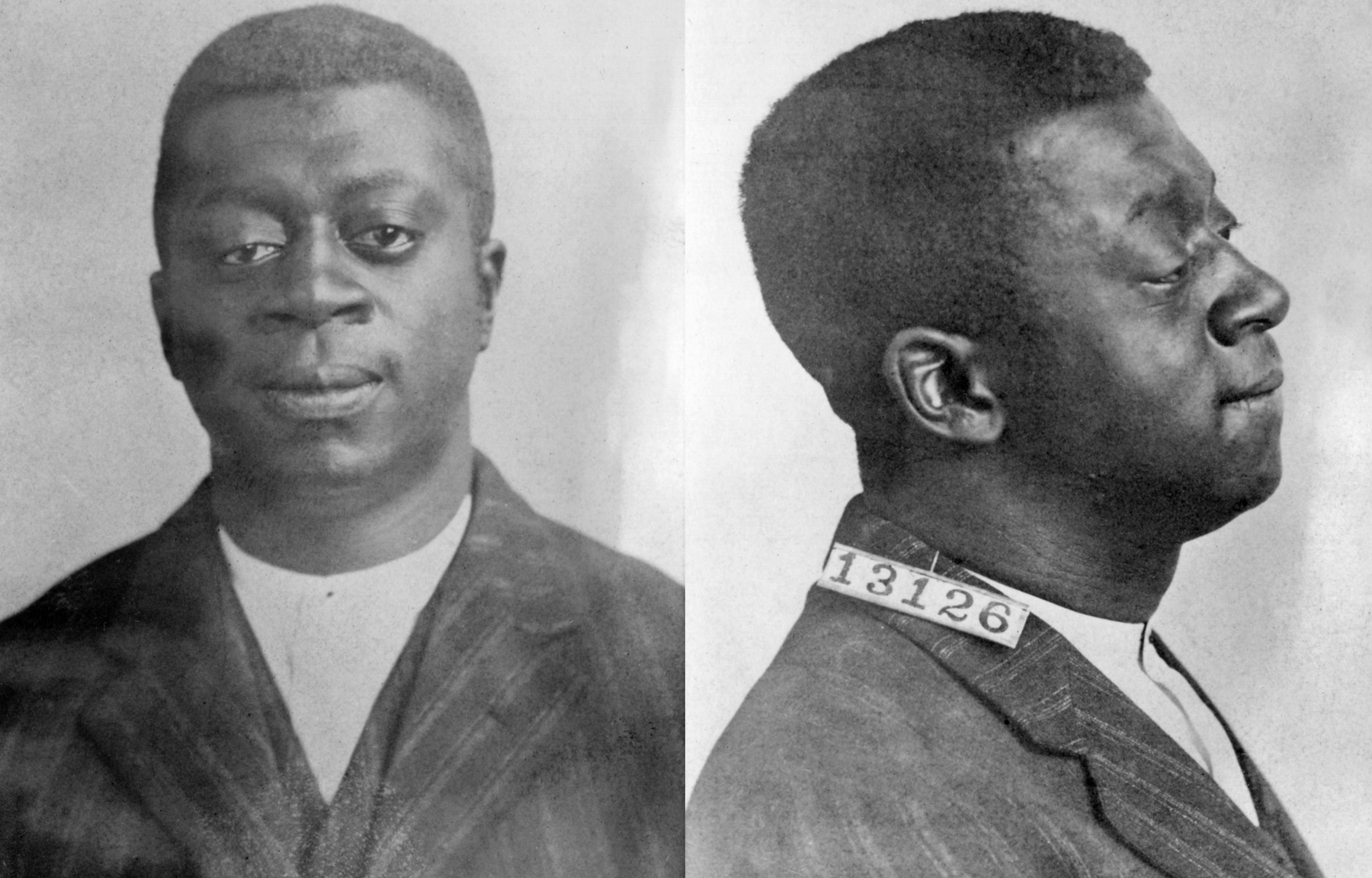

Never mind that he broke no laws. He was among the ninety-four Wobblies who faced federal charges under the Espionage and Sedition Acts, and with the others, he entered federal prison in Leavenworth in 1918. Released temporarily on bond in 1920, defended by leading Black intellectuals as well as the weakened IWW, Fletcher had his sentence formally commuted two years later. He had already resumed agitation in Philadelphia, drawn into political controversy when he rejected the appeal of the badly factionalized and ready-for-revolution newborn American Communist movement. Lenin’s decision for American followers to leave the IWW and rejoin the AFL prompted a power struggle that only the employers could finally win.

Local 8 failed, but Fletcher remained in the IWW, a touring agitator and champion soap boxer, until he suffered a stroke in 1933. Little more is known about Fletcher, save his divorce and second marriage, to a woman of color, and his life in Brooklyn as a handyman until his passing in 1949. We do know, from reminiscences included here, that Fletcher became part of a rich milieu of older Wobblies, found in many parts of the United States during the 1940s-70s. Exceptionally kindly folk, eager to greet the New Left as spiritual grandchildren of the rebellious pre-1920s movement, they regaled and encouraged us along.

The bulk of this invaluable volume, the major source of its dramatic expansion in size since its original 2006 release, is documentation. The details offer an untold history of a Black radical, documenting his struggles, samples of his writings, and the way his contemporaries remembered him. Readers will find much for themselves here.