By Erik Loomis

Lawyers, Guns & Money

April 18th, 2021

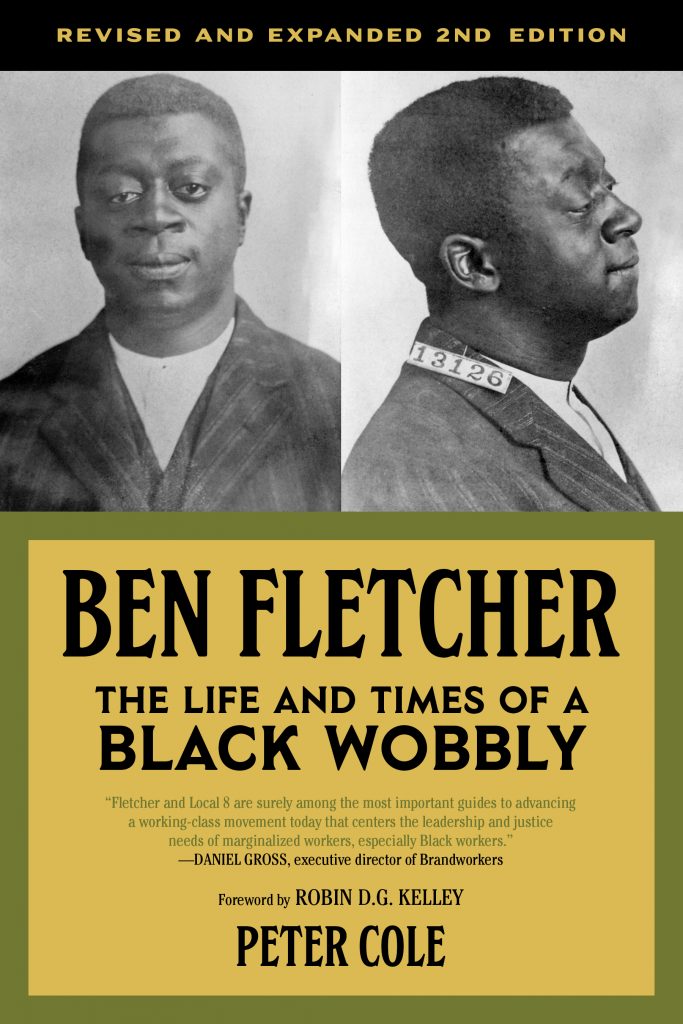

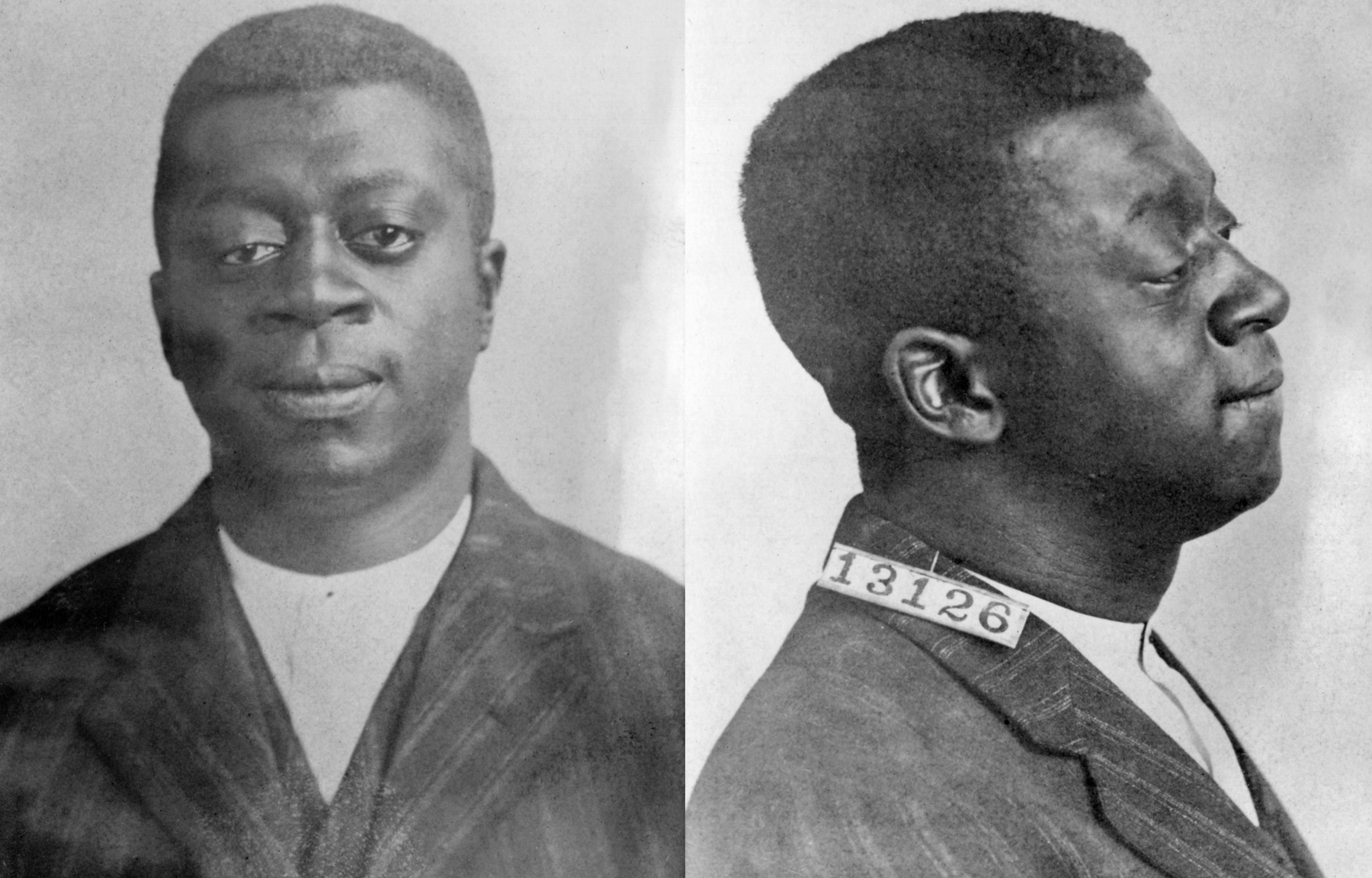

The labor historian Peter Cole lays out the main points from his new biography of the little known Black Wobbly Ben Fletcher and they are well worth your time this Sunday morning.

Never graduating from high school, Fletcher joined hundreds of thousands of rural Black and White Americans and European immigrants who sought work in America’s third largest city, an industrial behemoth that produced everything from battleships to buttonhooks. However, most employers refused to hire Black people, thereby confining them to low-wage jobs, including loading and unloading ships along the Delaware River. As a teen, Fletcher probably walked the mile or so from his South Philly apartment to the riverfront to “shape up,” the abusive hiring system that pitted workers against each other and forced them to bribe hiring bosses for a day of backbreaking, poorly paid work.

In 1910, Fletcher joined the Industrial Workers of the World, the country’s most colorful and radical union because of its unapologetic embrace of socialism and internationalism and rejection of racism, xenophobia and sexism. Five years earlier, the IWW was founded by an assortment of leftists, including Eugene Debs, much-loved leader of the Socialist Party; Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, legendary organizer of coal miners and child labor abolitionist; “Big Bill” Haywood, leader of the most militant, socialist union of Western miners; and Lucy Parsons, the Black anarchist and widow of Albert Parsons, a Haymarket “martyr” from Chicago’s eight-hour movement. These radicals founded a union whose purpose was no less than overthrowing capitalism worldwide. The IWW preamble boldly declared: “There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things in life.”

Wobblies, an affectionate term for members, also rejected the mainstream unions belonging to the American Federation of Labor which, because of prejudice, refused to organize most Black, female and immigrant workers and possessed no agenda beyond short-term, incremental improvements to members’ wages and conditions.

Fletcher embraced the socialism and anti-racism of the IWW as well as its solution: militant unions deploying workers’ greatest tactic — the strike. Strikes could help workers win short-term economic gains in advance of a general strike to achieve the Wobblies’ revolutionary goal, “Abolition of the wage system.”

Fletcher appreciated that the IWW committed itself to fighting racism. As he wrote in 1929, “long ago I have come to know that the Industrial Unionism as proposed and practiced by the IWW is all sufficient for the teeming millions who must labor for others in order to stay on this planet, and more, it is the economic vehicle that will enable the Negro Workers to burst every bond of Racial Prejudice, Industrial and political inequalities and social ostracism.”

The IWW was often better at anti-racist rhetoric than anti-racist action. After all, its core was still made up of white folks who brought a lot of history with them to it. But there are cases such as Fletcher when real multiracial unionism could take place. The history of Black unionism is central to the larger history of Black civil rights activism and figures like Fletcher are key to our understanding of it.