By Chris Spannos

Taking anti-nuclear direct action at the height of the Cold War and supporting rank-and-file industrial workers throughout the second half of the twentieth century, engineer and shop steward Ken Weller, who died at the age of 85 on 25th January, was among Britain’s best working-class militants.

As co-founder of the irreverent libertarian socialist group Solidarity, which was most influential between 1960 and 1975, Ken was also the convenor of the Industrial Sub-Committee of the Committee of 100 (C100), in which he and other Solidarity members on the radical wing promoted direct action. In autumn 1961 Ken and a handful of other activists occupied the Russian Embassy in London to protest the Soviet ‘workers’ bomb’.

Ken was believed to be among the last surviving members of the ‘Spies for Peace’ who took direct action in 1963 to expose state secrets in which an elite planned to govern Britain in the wake of a nuclear attack. These revelations provoked a public crisis of confidence in the British state. A manhunt for the ‘Spies’ ensued but, despite a police search and raid, which included Ken’s house, none of the peace activists were ever caught.

Ken was born on 30th June 1935 in what was then the Royal Free Hospital in Kings Cross. His first years growing up in Islington were cut short by Hitler’s ‘Blitz’ on London which killed more than 40,000 civilians. Ken sometimes reminisced about playing as a child in and out of the new tanks and armoured cars massed for the war effort on the 30-acre Caledonian Market. At the age of five he was evacuated and his elder sister took care of him. A year after returning to his family, Ken’s mother died. His father died when Ken was in his late teens.

As a child Ken attended a special school for disadvantaged children who were deemed exceptionally intelligent. He wasn’t very fond of the school and soon after got into politics.

Many of Ken’s relatives passed through the Communist Party and Ken followed step by joining the Youth Communist League (YCL). However, he broke this family tradition when the Soviets suppressed the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, his understanding sharpened by Peter Fryer’s pragmatic first-hand reports in the Daily Worker, which the paper soon refused to carry. This and other events led Ken to increasingly view Communism as counter-productive, a critical perspective on the Party which resulted in his expulsion.

Ken joined Gerry Healy’s Trotskyist group The Club in 1959. Soon after it became the Socialist Labour League (SLL) and Ken was taking part in critical discussions, forums and meetings composed of dissident party members. These meetings addressed issues such as working-class historiography and helped shape Ken’s own approach to labour and anti-war history.

In May 1960 Gerry and his supporters, notably the radical neurologist Chris Pallis, expelled Ken and other dissidents. Soon after, Gerry expelled Chris too, but later that year Chris and Ken, along with other SLL exiles, co-founded the highly influential political grouping Solidarity. The two men developed a remarkably close friendship and a rare political relationship.

Influenced strongly by the French journal Socialisme ou Barbarie, in particular its leading thinker Cornelius Castoriadis, Solidarity sought to advance autonomous working-class action by participating in the shop steward movement, supporting industrial militants and publishing accounts of workers’ struggles. Solidarity translated the work of Castoriadis into English and applied his analysis of society divided into order givers and order takers to critique trade unions, traditional parties of the left, and bureaucratic society.

Over the course of Solidarity’s existence, Ken produced popular articles and pamphlets that leveraged his own experience as an industrial militant to advance the premise that the problems in industry could only be solved by the actions of the workers themselves. Between the late 1950s and early 1960s Ken worked in a film library in the parish of Clerkenwell, later around Covent Garden as an electrician for the London Electricity Board, then for Standard Telephones, and as shop steward for the Amalgamated Engineering Union, jobs which further developed his analysis of management’s conflict with the rank-and-file.

In the early1960s he met his partner Gwyn Owen through C100 activism. They moved to north Wales where Ken studied at Coleg Harlech and their son Owen was born. From Wales, the new family returned to London to live in Pimlico, near Tate Britain, for a year before Ford Dagenham offered Ken a job in 1969. Then they moved to East Ham.

At the age of 35, and some 18 months into working at Ford, Ken was driving his motorcycle home in the early hours of the morning, after a night shift, when an off-duty police officer driving under the influence of alcohol came out from a side street and hit him. Ken’s arm, leg, and pelvis were broken in the accident.

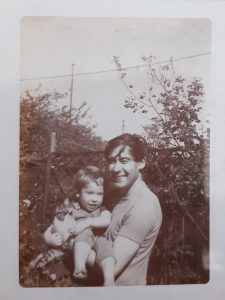

A year after the motorcycle accident, Ken and Gwyn separated. While he recovered from the accident to a degree, and could walk about, he was not able to work. Ken was raising Owen, just a toddler, as a single parent. He would carry Owen around the block on his shoulders singing the nursery rhyme ‘I had a little nut tree’.

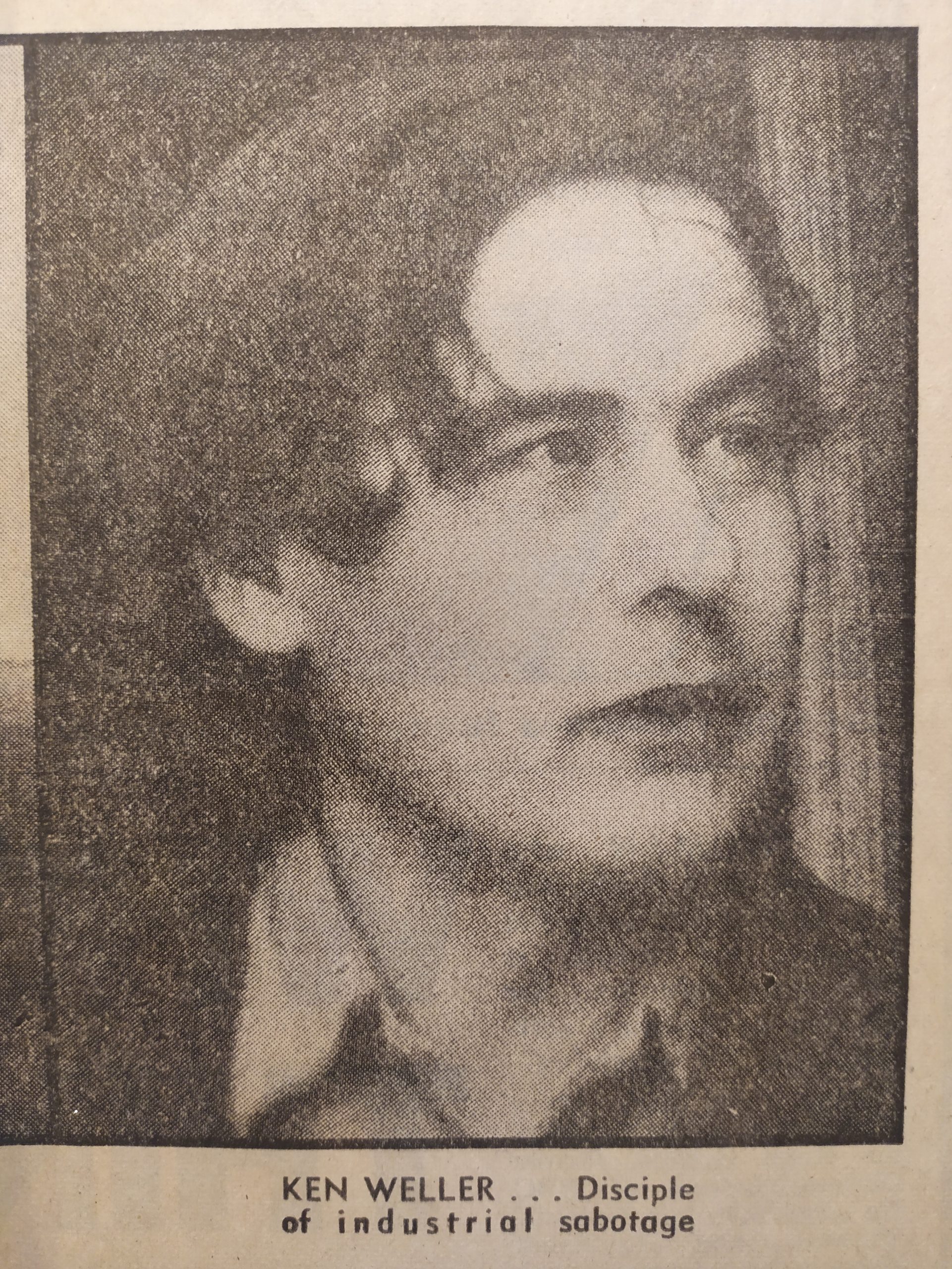

Despite these challenges, Ken continued to be an effective pamphleteer. In October 1972, the News of the World sensationalized Ken’s pamphlet ‘Strategy for industrial struggle’, penned under his nom de guerre ‘Mark Fore’, which examined informal resistance to production, sabotage, occupations, sit-ins, and other methods of resistance.

Without mentioning his debilitating motorcycle accident, the tabloid referred to Ken as ‘the man with no job’ who has ‘plenty of time to mull over his interest in sabotage.’ This caricature was wrong only insofar as Ken would have likely preferred to mull over ever evolving lessons for militant struggle drawn from an active work life, as he had done up to his accident.

Ken’s 1973 pamphlet ‘The Lordstown Struggle and the Real Crisis in Production’, told the story of what happened in General Motors’ Ohio plant in Lordstown between 1971 and 1972 in order to highlight trends of political struggle and their consequences for revolutionary socialists.

In the mid-1970s, there were times when Ken was feeling better. He was doing things and he got back in touch with people.

He had a girlfriend who lived in Holborn and he used to take Owen down to the river Thames. They would sit at a pub that overlooked the river and he’d buy Owen a coke and crisps. ‘Those were happy times,’ Owen recalled. ‘He used to take me to play crazy golf at Barking Park.’

Ken continued to participate in Solidarity, but from the late1970’s to the mid-1980’s, his personal life became more difficult. His house was becoming run down and he was in debt. He put on a strong face and didn’t reach out to family or indicate he was struggling.

‘It was hard for him to cope, and he tried not to show it,’ Owen remembered. ‘That’s why he didn’t get in touch with people, because he didn’t want them to see that he had too much on his plate. I think he was suffering from depression.’

Still, through this period Ken did more than anyone to keep Solidarity magazine going by acting as business manager and hosting editorial meetings.

One thing that helped him through difficult times was music. He told his friend, historian David Goodway, that music kept him on an even keel. ‘He was particularly keen on Ray Davies and The Kinks.’

Through the early-to-mid-1980s Ken also threw himself into his book ‘Don’t be a Soldier!’: The Radical Anti-war Movement in North London 1914-1918. Writing this book took up a lot of time during that difficult period. And as Owen saw it, ‘It helped him’.

In his book Ken thanks friend Stuart Hathaway, for ‘…correcting my abominable syntax, grammar and spelling…’. On this, Stuart reflects, ‘Ken wasn’t going to let a little thing like a lack of that sort of formal education stop him from doing something that he considered important. He never gave the slightest impression that he was either impressed or intimidated by people with better “paper qualifications”; the question was what you thought and did’.

By the late 1990s, Ken’s health was stabilising. He kept in good spirits over the following decade, despite developing arthritis in his knee and, around 2000, having a metal joint placed in his knee. But from 2010 his physical condition worsened. The joint became infected in 2014 and sepsis nearly killed him.

Recurring health problems and two major operations left Ken bed ridden. Owen moved back home to take care of him for the last seven years of Ken’s life, during which friends would visit and call, and he experienced many good moments.

To receptive ears Ken was always ready to recount the history of Solidarity. He was most proud of how the group took direct action to support militant struggles – from the 1961 Spies for Peace action, the 1965 Kent housing struggle, to its support for various rank-and-file labour movements – over the group’s 30-year existence.

Warm, humorous and too humble of his own capacities, Ken was never known to have had a bad word to say of any individual; but about the 57 varieties of how individuals combine in political groupuscules, and the resulting group think, he was side-splittingly excoriating. He truly knew where the bodies lay buried.

Ken is survived by his ex-wife Gwyn, their son Owen, his middle sister Barbara, and two nephews.

PM Press will be publishing a collection of Ken’s writings, a Ken Weller Reader, in 2022.

Friends and former Solidarity members share their thoughts and memories of Ken:

I first got to know Ken during the early days of the Committee of 100 and became a regular reader of Solidarity, including in Brixton and Lewes prisons after the Greek Embassy demonstration of 1967. He made a distinctive contribution to thinking on the independent left, taking neither a Stalinist nor Trotskyist perspective. His commitment and independence of thought will certainly be missed. — Michael Randle

I spent many hours in meetings with him in the 70s and 80s. I never met anyone with a more intense intelligence, a better detector for nonsense or a more thorough assessment of what was happening. He had both his heart and his mind in the right place and taught those of us who spent time with him not just some really important ideas but also how to think really critically about the ideas of others. I feel I owe him a huge debt of gratitude. — Andy Brown

Ken’s house in East Ham was a welcome venue for meetings of the East London Libertarians. On my wall I have a black and red beautifully produced poster, reading:

First in a series of public meetings

Industrial Struggle and Trade Unions

8pm Wednesday 15 September 1976

123 Lathom Road E6

Organised by East London Libertarians

As I recall, we met regularly at Ken’s for some years. And on Saturday 11th March 2000, Ken gave a talk at the monthly News from Nowhere Club in Leytonstone, entitled ‘What Went Wrong with Socialism?’ He was billed as a ‘Renaissance’ man, with an industrial background, involved with Solidarity, and living in East Ham. Ken is a real loss to the libertarian left but we can try to continue his spirit. — Ros Kane

Ken was a smart and principled man with a reserved and watchful manner on first acquaintance. As a comrade he was physically brave and where necessary capable of efficient violence. Once you knew him, however, he was a fount of knowledge on and experience of UK left politics with a ready sardonic humour when talking about it. He was a working-class self-taught scholar. He knew and had experienced so much. He was a democrat (small ‘d’!) and particularly disliked the conniving and opportunist ways of the leaders of left political groups and union officials. He was too modest about his abilities. — John Quail

Words that occur to me if I think of Ken are: intelligent, straight-forward, down-to-earth, enthusiastic. I seem to remember he was very knowledgeable about all sorts of people in Left politics and the labour movement more generally. — Bob Dent

The most significant thing about Ken for me was that he was a genuine working-class militant in the best tradition, by which I mean that his politics grew out of his work experience rather than theoretical ideas, and that he was self-educated after school rather than in it. I related to him because we were both very interested in history. He wasn’t one to talk about himself. I don’t know who he regarded as friends though I guess it was his comrades of an earlier generation and the anti-war militants of the early sixties. You came round, for a group meeting or to see him, he made you a cup of tea and smoked his roll-ups and that was it. He wasn’t – in my experience at any rate – light-hearted and jovial; I don’t recall any Ken Weller jokes. But I never heard him complain or express any resentment about his lot or relative poverty. Perhaps that reflected his general temperament. — Stuart Hathaway

Ken was well-respected, especially having had industrial and trade union experience. He was liked – because he was easy-going and listened to people. Not dogmatic. Not a firebrand! Some of my favourite memories of Ken include meeting in the very informal surroundings of his house in East Ham, with quite a few papers, pamphlets, etc, scattered around. My memory of meetings is there was never any confrontation, and all contributions to discussion were welcome. (I hope I’m not looking back through rose-coloured glasses… it was a long time ago!). Libertarian socialism in action! To me, what stood out most about Ken was that he had a lot of experience and knowledge of political tendencies and was open to discussion while holding on to a revolutionary libertarian socialist viewpoint. He had a catch-phrase that has stayed with me: ‘it’s more complicated than that!’ I remember he also used (presciently) the term ‘factoid’ where we would now speak of ‘fake news’. I also recall that Ken was clearly fond of Owen, and shared (I believe) Owen’s love of reggae. — Ian Michael Pirie