By Peter Cole

New Frame

January 13th, 2020

As an organiser and orator for the Industrial Workers of the World – historically, America’s most radically inclusive union – Ben Fletcher was a working-class hero in his time.

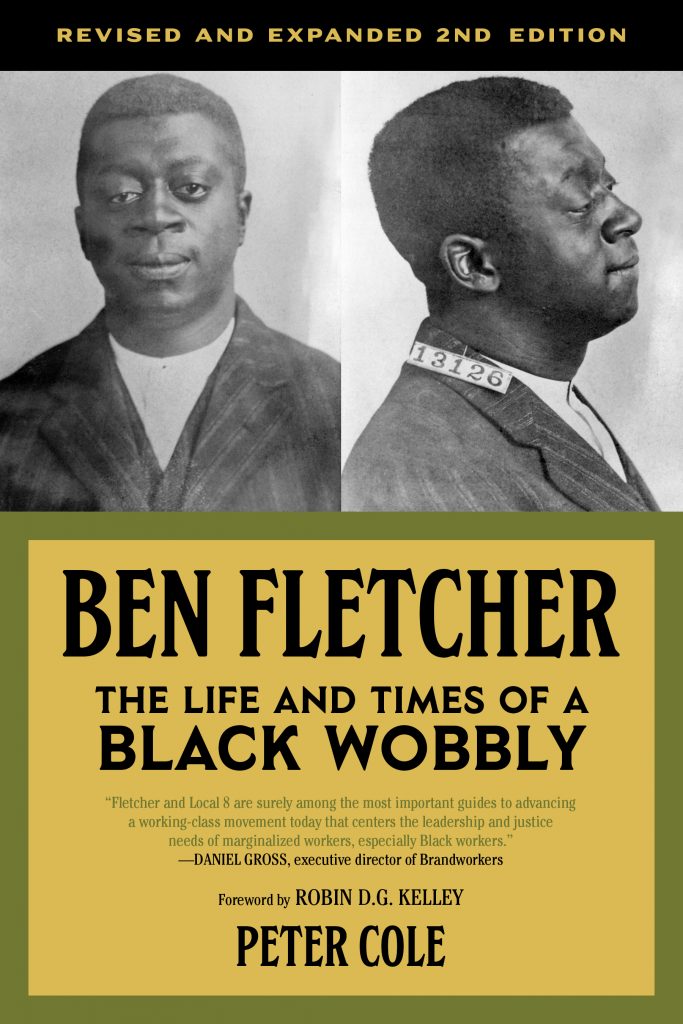

This is a lightly edited essay by historian Peter Cole, along with an excerpt from his book, Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly (PM Press, 2021).

Benjamin Harrison Fletcher surely ranks among the greatest African Americans of the early 20th century and top echelon of Black unionists and radicals in all of US history. Fletcher helped lead a pathbreaking union that likely was the most diverse and integrated organisation (not simply union) of his time and despite that era’s rampant racism, anti-unionism and xenophobia. Along with thousands of his fellow Philadelphia dockworkers, he helped found and lead Local 8, affiliated with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Perhaps the most radical unions in all of US history, the IWW also was the first predominantly white union in South Africa to actively organise African workers. IWW members were, and still are, affectionately known as Wobblies. If one has heard of militant Black American organisers of the 1960s, like Fred Hampton, Ella Baker or Stokely Carmichael, one should know about Fletcher. Yet, today, Fletcher is unknown save for aficionados of African American labour and radical history.

Born and raised in Philadelphia, then the country’s third largest city, in the late 1880s Fletcher’s parents escaped the racist horrors of the South – not long after the end of the Reconstruction era, which should be understood as a Southern white counter-revolution to preserve white supremacy. One might compare the migration of Fletcher’s parents to Philadelphia as similar to the Sicilian immigrants travelling aboard ships to escape desperate poverty though, more accurately, African Americans migrating from the South also could be compared to Russian Jews who fled the murderous, anti-Semitic pogroms in late 19th century Russia. In the working-class slums of south Philadelphia, African Americans like the Fletchers lived on the same streets as East European Jews and Italians, as well as poor and working-class Poles and Lithuanians, Irish and Irish Americans and more (only later did residential segregation occur). Philadelphia proclaimed itself “the workshop of the world” and, alongside Chicago, Pittsburgh and other industrial cities, had made the United States into the world’s mightiest industrial powerhouse. Fletcher was one of the countless thousands of young men who walked a kilometre or two to the Delaware River waterfront, looking for a day’s work to support themselves and their families. These sons of peasants – no daughters, then, loaded and unloaded cargo ships – submitted themselves to the “shape-up”, an oppressive hiring system, in order to get hired to work in one of the country’s busiest ports. The unloading of vast amounts of coal, iron, cotton, sugar and other raw materials and loading of all sorts of manufactured goods – everything from buttonhooks to locomotive engines – meant thousands of backbreaking, dangerous, low-paying jobs for desperate men with strong backs.

Dockworkers in Philadelphia, like in most other port cities, were horribly exploited by powerful employers in the global shipping industry. The majority of dockers lived in poverty. Even worse, every single day they walked onto a quay or ship, they risked being killed because their trade was among the most dangerous. What these workers needed – and which many including Fletcher understood – was a labour union to represent them. However, their own diversity was a potential obstacle. In 1913, when Fletcher helped organise Local 8, Philadelphia’s waterfront workers were roughly one-third African American, one-third Irish and Irish American, and one-third immigrant from other European countries. However, in early 20th century America, most unions excluded Asian, Black and Latinx workers due to pervasive racism and xenophobia.

By contrast, the revolutionary Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) actively recruited people of colour, in keeping with their emphasis on class solidarity and its legendary motto: “An Injury to One Is an Injury to All!” The Wobblies! Even their nickname demands one sit-up and take notice. WEB du Bois, a co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and editor of its influential monthly, wrote: “We respect [the IWW] as one of the social and political movements in modern times that draws no color line.” Of course, it was Local 8, led by Fletcher, that turned the Wobblies’ antiracist vision into that reality. In short, Fletcher and a bunch of so-called “unskilled” working-class Black and white folks, native-born and immigrant, managed to do what most American institutions still have not achieved in 2021: equality and integration.

South Africans who know their history well or are involved in the trade union movement should recognise the IWW slogan because it adorns many a South African union’s banner including the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu), founded in 1985. The motto has a much longer history in southern Africa. Before World War I, the first Wobbly members – almost certainly sailors from somewhere in the British empire – arrived in Cape Town and started disseminating IWW literature including its slogan. South African scholar Lucien van der Walt has been researching the IWW and other such radical unions for decades. No later than 1910, the IWW started organising in South Africa, an era when most unions embraced a racist “White Labourism” ideology that excluded Black workers. In the 21st century, the irony of so-called socialists who refused to organise the vast majority of working people is painfully obvious. Nevertheless, it was the norm.

Related article:

A handful of open-minded, socialist workers started to listen to IWW notions that formed branches of the IWW in South Africa, leading strikes of tram workers in Johannesburg in 1911, and forming locals in Durban and Pretoria. While the IWW did not grow much, other unions soon followed that adopted the IWW’s antiracist ideals including the International Socialist League, Industrial Workers of Africa, Indian Workers Industrial Union and sections of the early South African Native National Congress. Most importantly, the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union of Africa (ICU) emerged, in 1919, and led a strike of 2 000 dockers in Cape Town.

The ICU, which also could be read as “I see you”, was led by Clements Kadalie, a migrant from British-controlled Nyasaland (now Malawi) who became the first great Black unionist in southern Africa. While the dockers’ strike had not succeeded, the ICU – which adopted the IWW motto – grew and spread rapidly in the early 1920s. By 1925, the ICU constitution had incorporated the IWW preamble, which began as follows: “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life.” By the mid 1920s, more than a hundred thousand Black men and women had joined the ICU – not just in South Africa but also in South West Africa (now Namibia), Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia). No doubt, the ICU’s embrace of IWW ideals, including its motto, helps explain why it is emblazoned on the banners of many South African unions including the South African Transport & Allied Workers Union and many others including in Cosatu.

My new book, Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly, in a real sense helps South Africans understand the ICU’s ideology, even though my book primarily tellsthe story of one of the greatest heroes of the US working class and his revolutionary union.

For years, I have carefully researched his life, painstakingly uncovering a stunning range of documents related to this extraordinary man. Ben Fletcher is the most comprehensive look at one of the greatest African American radicals that almost no one has heard of. The revised and expanded second edition includes a detailed biographical introduction of his life and history, reminiscences by fellow workers who knew him, a chronicle of the IWW’s impressive decade-long run on the Philadelphia waterfront in which Fletcher played a pivotal role, and nearly all of his known writings and speeches.

Today, the United States remains hobbled by the era’s soaring inequality and racism, which launched the largest wave of US protests in favour of racial equality in half a century. My book gives Fletcher’s timeless voice an opportunity to inspire a new generation of workers, organisers and agitators. Below are excerpts from three documents included in the book.

Soapbox speaker

This brief report is the first-ever mention of Fletcher in the public record. It is not certain when he joined the IWW, probably in 1910 or 1911. In 1912, at 22 years of age, Fletcher already was an important local organiser and speaker. The IWW had been operating in Philadelphia for years, chartering its first local – of Hungarian immigrant metal workers – in 1907. Like Philadelphia, Chester lies along the banks of the Delaware River, about 15 miles south (downriver). The magazine Solidarity was one of the IWW’s two main English-language publications in the US during this era. That the IWW already sought to organise African American workers is noteworthy since almost no other union in the United States then did so due to pervasive racism.

In a time before radio, television, mobile phones or the internet, literally the most efficient way to reach people was by standing on a “soapbox” on a busy street corner and speaking to pedestrians. Also of note, in early 20th century America, the term “coloured” was the polite term for Americans of African descent.

We are pushing the work of propaganda around the town. Held a meeting at the corner of Third and Edgemont streets. Chester. On Saturday, July 20, with Benjamin H Fletcher as the main speaker. Fellow worker Fletcher is the only coloured speaker we have here, and certainly knows how to deliver the goods. The crowd was very attentive, taking to everything the speaker had to say regarding the class struggle. We sold a bunch of Solidarity and a lot of literature. The negro workers are greatly interested in the IWW, and I believe we shall get a local started in Chester in the near future, as there is a bunch of coloured workers anxious for the One Big Union.

– Howard Marston, Solidarity, 22 July 1912

Fletcher nearly lynched in Norfolk

This is the only known interview with Fletcher and is quite extraordinary. It reveals much about Fletcher, including his unwavering commitment to the IWW and, more broadly, ongoing commitment to revolutionary industrial unionism – even in the face of a potential lynch mob of white Southerners! While the interviewer is unknown, the Amsterdam News is a weekly newspaper founded in 1909 and geared to the Black community of New York City.

Among the older, still-operating Black newspapers in the United States, it is named for Amsterdam Avenue, a major street in Harlem. The paper long has been a voice for equal rights and none other than Malcolm X wrote a column in it. Its workforce unionised in 1936 and remains so.

“I was preparing the longshoremen of Baltimore for a strike in 1917 for higher wages, shorter hours and better working conditions when I received instructions from headquarters to proceed to Norfolk where the dock workers were becoming restless and asking that an organiser be sent them,” Fletcher began.

“I found the men responsive and eager for a union. But I had not been in town long before word was circulated that I represented a dangerous element set on the destruction of property and the overthrow of the government. Then I began receiving messages of a threatening character. I would be lynched if I spread that doctrine around Norfolk, I was told. One night friends, fearing that my life was in danger, smuggled me aboard a northbound ship to Boston.

Related article:

“By this time the government spurred on by the lumber and copper interests of the West had set about a deliberate plan to eradicate the IWW, which was growing rapidly in numbers, gaining control of certain important industries, and threatening the supremacy of the American Federation of Labor, which the government consistently favoured throughout the war period.

“It was while I was working in Boston that I received a tip that I was in line for indictment by a Federal Grand Jury. Accepting this tip as authentic I returned to my home in Philadelphia, where I preferred to be placed under arrest. The next week I read in the paper that indictments had been returned against 166 of us and that we were to be arrested on sight.”

Ben Fletcher paused long enough to relight his cigar and to glance reflectively about the room; to think again of the days when his organisation was a rallying ground for the revolutionary workers of the country; when it constituted enough of a threat to compel the attention of the government; when it had cards issued to a million workers including 100 000 Black men and women whose membership was discouraged or barred by the American Federation of Labor unions. Times have changed and now with its scant 3 000 dues paying members it is little more than a proletarian sect.

“For more than months,” he said, taking up the thread of his narrative, “I remained in Philadelphia, a fugitive from justice yet going about my work with no effort to conceal my identity. During this period I was working in a roundhouse [locomotive maintenance shed built around a turntable] of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

“One day – it was 9 February 1918 – two strangers appeared at my door. They were special agents of the government. They placed me under arrest and I was held in $10 000 bail. After being imprisoned for two weeks bail was reduced to $1 500 by the Federal district attorney. This was secured by the IWW local and I was released.

“Summoned to appear in court in Chicago on 1 April, I arrived two

hours late due to a train wreck. Making my way through the Federal

agents and police who swarmed the corridors I was blocked at the

courtroom door by the chief bailiff, who inquired:

“‘What do you want in here’?”

“‘I belong in here.’”

“‘Oh, a wise boy from the South side want to see the show’?”

“‘No, I’m one of the actors’.”

“Take that stuff away. You can’t get in here’.”

“Insisting

that I belonged there I pulled out my card and told him to go in and

see if Ben Fletcher’s name wasn’t on the indictment. He left the door in

charge of assistants, went in and returning announced: ‘He’s Ben

Fletcher, all right. Let him in.’

“And then I walked into the courtroom and into the Federal penitentiary.’”

– “Some People Are Taken to Jail, But Ben Fletcher Just ‘Went In’,” Amsterdam News, 30 December 1931

To defeat racism, join the IWW

In 1929 Ben Fletcher engaged in extensive correspondence with Abram Lincoln Harris, a radical Black historian and economist of Howard University, the most prestigious “historically Black” university in the country. Along with scholar Sterling Spero, Harris was writing what remains one of the best histories of African American labour, The Black Worker (1931).

Needless to state I am glad to note that you are developing that theory of industrial unionism and negro workers’ fortunes are bound up therein. I have been identified with the labour movement – 20 years, and I am at a safe distance from 40 yet. Nineteen of those years have been spent in the ranks of the IWW and this long ago I have come to know that, the industrial unionism as proposed and practiced by the IWW is all sufficient for the teeming millions who must labour for others in order to stay on this planet, and more, it is the economic vehicle that will enable the negro workers to burst every bond of racial prejudice, industrial and political inequalities and social ostracism.

– Abram Lincoln Harris Papers, Moorland-Spingarn Archives, Howard University, Washington, DC.

Peter Cole is a professor of history at Western Illinois University in Macomb and a research associate in the Society, Work and Development Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. Cole is the author of the award-winning Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area and Wobblies on the Waterfront: Interracial Unionism in Progressive-Era Philadelphia. He coedited Wobblies of the World: A Global History of the IWW. He is the founder and codirector of the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project.