By Susie Day

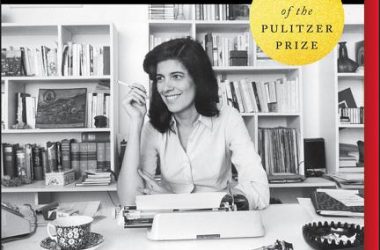

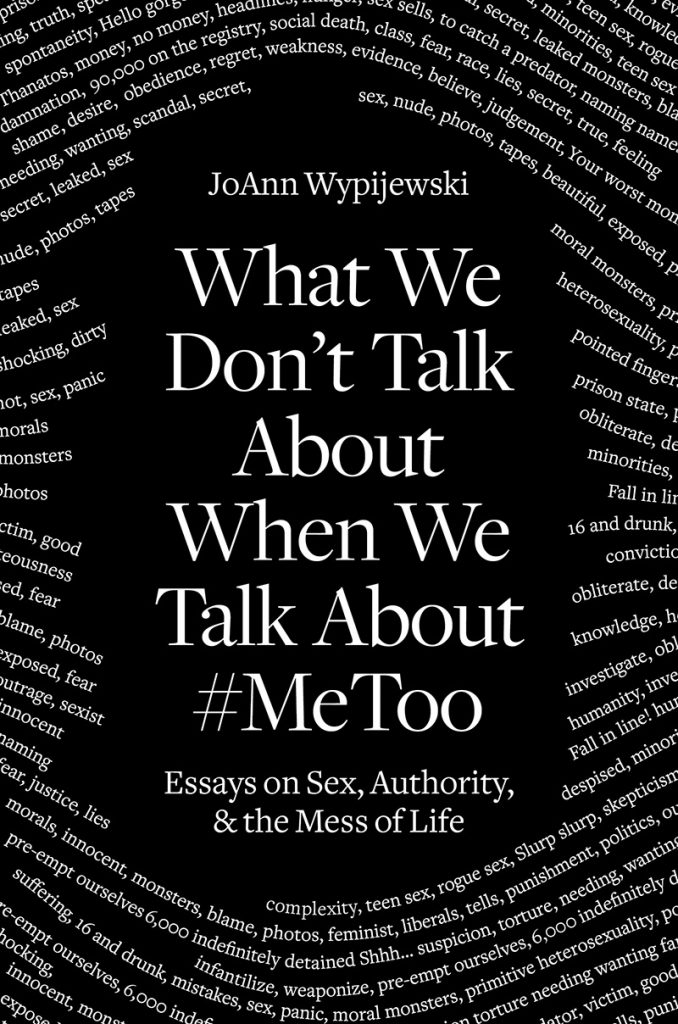

[What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About #MeToo: Essays on Sex, Authority & the Mess of Life JoAnn Wypijewski, Verso, 2020]

Some years ago, a friend – an ardent gay activist – phoned me, ecstatic, nearly weeping with joy. She had just come from a courtroom where two Queens men, charged in the beating and stabbing death of a gay man in a Jackson Heights cruising area, had actually been convicted. Even better, the pair now faced 15 years to life in prison. Like all of us in the queer community, I had been sickened and angry at hearing of yet another gay-bashing. But this verdict didn’t feel like victory. And the celebration that erupted – our community-wide gratitude that society had finally deemed us human enough to send our murderers to rot for years in prison – did not feel like liberation.

JoAnn Wypijewski might call this joy at “justice” a movement manifestation of “unity through vengeance.” Wypijewski has spent most of her life hacking through the psychological underbrush that entangles humanity’s efforts to create good and judge evil. Most recently, she’s written of the multi-layered, cross-cultural sensation known as #MeToo, but she’s also paid close attention to decades of outrage and scandals. What she’s found is panic – in particular, “sex panic.”

Generated panic is how societal power, in its infinite forms, controls our individual feelings of rage or grief at real atrocities, and manipulates them into collective, law-and-order-fed lust for revenge. So it’s probably past time that Wypijewski brought out a collection of her essays and called it What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About #MeToo: Essays on Sex, Authority & the Mess of Life.

That shape-shifting “mess of life” is mighty deep. We’re all swimming around in it, and those of us who identify as activists or work somehow for societal change are no exception. We don’t easily see how deeply power – personal, political, institutional, media, governmental power – runs through our lives. “They say power is cunning,” writes Wypijewski, “power is a hydra; it has more heads than any story … can describe.”

Most of us second-wave feminists grew up to that old adage about sexual violence not really being about sex but about power. But don’t people read most forms of power as at least a little sexy? In the face of BREAKING!! mainstream news, revealing, say, another Harvey Weinstein victim, we’re often swept up in the melodrama of what Wypijewski calls “bleached tale[s] of monstrosity and cowering,” and are apt to forget, when dealing with “monsters” like Weinstein, such basic humanitarian principles as due process or the presumption that accused people are innocent until proven guilty.

Most significantly, we’re never asked to entertain the prospect that the guilty can change and be forgiven. Wypijewski’s remarks on the excesses of #MeToo can be applied to other popular cries for justice: “Strip the veneer of liberation, and an enthusiasm for punishment is palpable. Look beyond the declarations of revolution, and there is an under-analyzed concept of patriarchy.”

What We Don’t Talk About is a dauntless, provocatively ethical book that asks moral questions. Foremost is, why, in our various fights for justice, must those judged guilty automatically be deprived of their humanity? Why do we, who seek equality and liberation, need to make monsters?

Wypijewski relentlessly takes apart many sex predator/sex transgressor stories that have galvanized (and warped) our collective imagination for years. She looks at how a Harvard law professor – the first African-American faculty dean – lost his position at an undergraduate house because he joined Harvey Weinstein’s defense team. She explores the murder of Matthew Shepard, fully considering the desolate lives of his murderers, whom the tabloids were happy to call “redneck trailer-trash.” She inspects the twisted media spin given to Nushawn Williams – that “one-man plague” and sex-perp extraordinaire – who, whether or not he transmitted HIV to multiple partners in the late 1990s, derived his monster status from the fact that he was Black and poor and slept with lots of “stupid or slutty” white women. And who can forget how news of Woody Allen’s alleged molestation of his stepdaughter drove millions of filmgoers to rethink their whole lives?

I’m especially grateful for a short, dead-on piece about Brett Kavanaugh, whose suitability for the Supreme Court was publicly contested mostly because of his alleged sexual assault, as a teenager, of Christine Blasey Ford – instead of Kavanaugh’s easily provable acquiescence, as assistant White House counsel, to U.S. policies of torture (sexual and otherwise) in outposts like Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo. Why don’t those victims matter?

And who are the predators among us who embody pure evil? Styles change. Wypijewski mentions the “poisoned solidarity” created by guilt-ridden white liberals whose media voices righteously condemn “the enemy” as being rich and white:

The enemy may be poor and black tomorrow … The validating enjoyment from demonizing ‘the right people’ is as dangerous as ever and unchanged. The situational view of rape is unchanged too: rape is a heinous crime, except when wished upon those accused of it.

Much of Wypijewski reminds me of the best of prison abolitionism – people like Angela Davis, for instance, contending how locking up George Zimmerman for decades for the murder of Trayvon Martin constitutes broken justice, good only for the prison industrial complex. But I wanted Wypijewski to investigate alternatives to prison, such as restorative justice programs. Maybe next book…

You may quarrel with some essays here. I had some misgivings in a chapter on the Catholic priest sexual abuse scandal, in which Wypijewski defines the North American Man/Boy Love Association mostly in free-speech terms. “NAMBLA is to sex in the 2000s,” she writes, “what the Communist Party was to politics in the 1950s.” I might have thrown the book across the room at this point, but it’s the 21st century, and I didn’t want to break my iPad. Whatever. Any movement concerned with liberation needs this book.

Wypijewski is inclined to discredit recovered memories of abuse, which, in deciding people’s legal fates, makes sense. Yet, regardless of the truth or believability of long-repressed trauma, people who feel they have been hurt still deserve to be heard – definitely not by “The View” but by us – fully and sympathetically. It’s our having to live with pent-up terror that leads us to create monsters in the first place.

© susie day, 2020

Source:

1991 gay bashing case:

“2 Accomplices Guilty of Murder In ‘Gay Bashing’ Case in Queens”:

# # #