By Steve Early

Counterpunch

June 12th, 2020

Younger radicals in the United States are today considering how to relate, personally and collectively, to the labor movement. Should they try to become agents of workplace change? Will serving on the payroll of local or national unions be supportive of such efforts?

Or should they organize “on the shop floor”—as teachers, nurses, or social workers—and then seek elected, rather than appointed, union leadership roles? Members of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) discussed this “rank-and-file strategy” at their convention this past summer, narrowly passing a resolution in support of it.

Other progressives, further down the rank-and-file road, are debating how to best support newly elected union reformers—and how to hold them accountable to the members who backed their insurgent campaigns. In some big city and statewide affiliates of the American Federation of Teachers or the National Education Association, left-led reform caucuses have continued to function, even after an electoral shift from old to new leadership.

Fifty years ago, activists who came of age in the 1960s grappled with the same questions during their initial challenges to the labor bureaucracy. Some had the foresight to transition from campus and community organizing to labor activism in education, health care, and service sectors, where college backgrounds were useful and job security good.

Other former student radicals—under the (not-always-helpful) guidance of left-wing parties and sects—opted to become rank-and-filers in steel mills, coal mines, and auto plants; the trucking and telephone industries; or other blue-collar fields. Unfortunately, in the 1970s and 1980s, de-regulation, de-industrialization, and global capitalist restructuring produced enormous job losses and union membership contraction. Many who made a “turn toward industry” lost any union foothold they had briefly been able to gain.

. . . Mike Stout’s . . . workplace and community organizing experience remains very relevant to [those] . . . who are trying to figure out how to link union reform activity to larger political struggles between labor and capital.

As we learn in his new memoir, Homestead Steel Mill—the Final Ten Years, Mike Stout’s journey took him down the latter path, but without it becoming a dead end, personally or politically. His workplace and community organizing experience remains very relevant to radicals, in any era, who are trying to figure out how to link union reform activity to larger political struggles between labor and capital.

Stout found his way to the shop floor at a time when few unions were hiring known troublemakers. He dropped out of the University of Kentucky in 1968 and joined anti-war protests at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago later that year. He then became a singer-songwriter in Greenwich Village and a peace movement organizer. His brief “flirtation with a U.S. communist organization” turned out to be “short and sour,” but it did produce a solid job lead in western Pennsylvania.

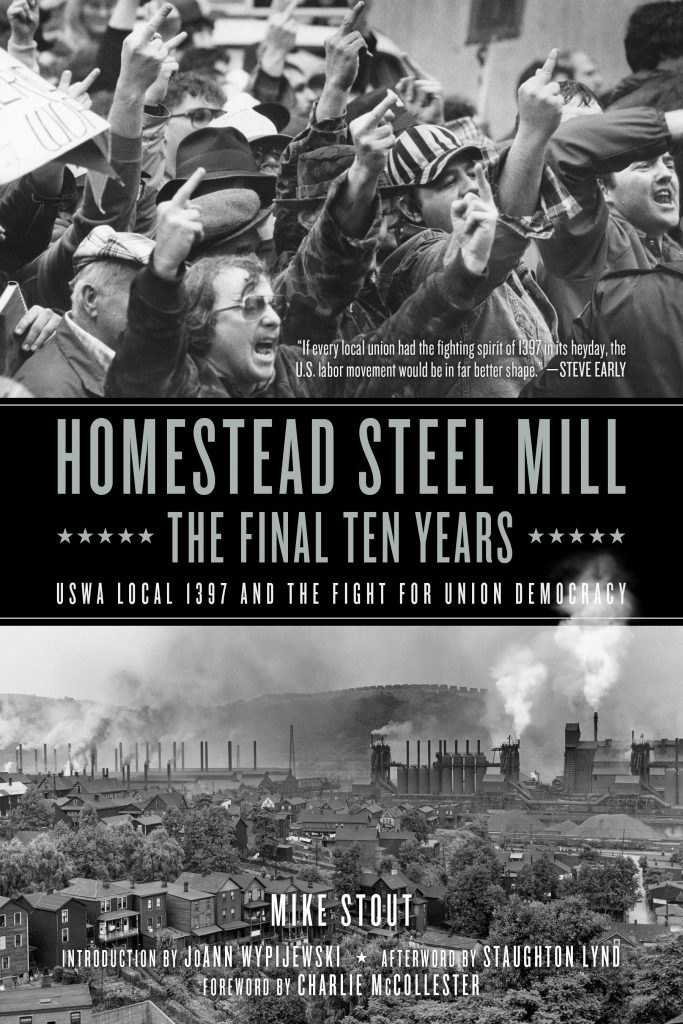

In 1977, U.S. Steel was on a hiring spree at its massive Homestead Works, a site of labor history lore—or infamy—as Andrew Carnegie deployed the Pinkertons to violently crush a strike by the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers in 1892. Ignoring Stout’s unusual (and probably sanitized) resume, the company made him a utility crane operator and dues payer to United Steelworkers (USW) Local 1397, already one of the most restive USW affiliates in the Monongahela (Mon) Valley.

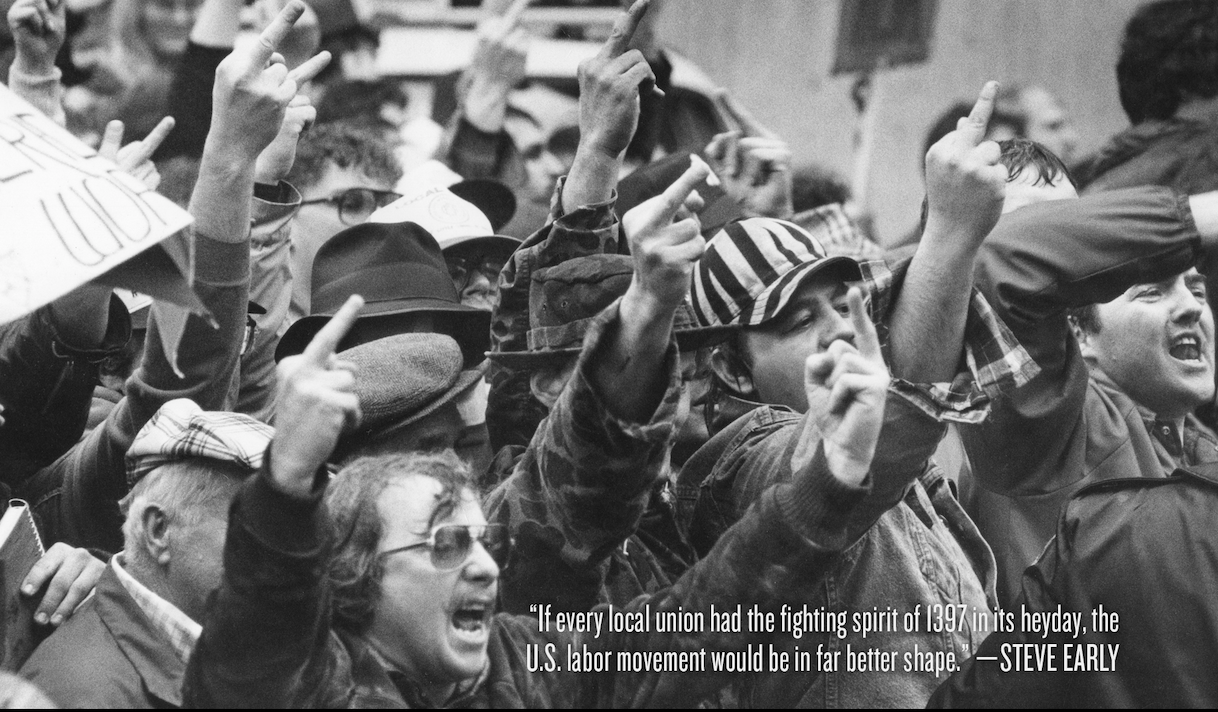

It was a decision that Homestead managers would later regret. Over the next decade, Stout and like-minded co-workers turned his seven thousand–member local into a key regional center for working-class resistance to the abuses of corporate power by U.S. Steel and other firms. Through non-stop agitation, education, and membership mobilization, Local 1397 also became a thorn in the side of top USW officials, located just a few miles away in the union’s national headquarters in downtown Pittsburgh.

Unfortunately, Stout’s career as a crane operator and then highly skilled union grievance handler was cut short by the collapse of the steel industry and closure of Homestead Works in the late 1980s. Yet Stout remained what labor historian Staughton Lynd calls a “long-distance runner.” He was able to transition from labor to community organizing and then to operating a co-operative print shop for twenty-five years. All the while, he remained a key figure in “steel valley” politics, cultural activities, and labor history circles.

Stout, for his part, believes that those now entering workplaces in “a neo-liberal world where technology, globalization, and deregulation have fundamentally changed and reduced our industrial and manufacturing base” do indeed have much to learn from past rank-and-file struggles in blue-collar industries. For example, Stout was not operating in some echo chamber of like-minded activists, all sharing the same high level of “working-class consciousness.” His fellow “mill hunks” could be ornery, suspicious of outsiders, and, by today’s standards, quite politically incorrect. Only by building many personal relationships with his co-workers was the author able, over time, to gain their confidence and respect and, in some cases, to influence their views.

During my own stint as a Pittsburgh-based volunteer for Ed Sadlowski’s campaign for the USW presidency in 1976-1977, I met some of the Homestead workers profiled in Stout’s book. Based in Chicago, Sadlowski was the reform-minded leader of USW District 31, which covered about one-tenth of the union’s then 1.4 million members. Only thirty-nine years old at the time, Sadlowski broke with his older, more conservative colleagues on the USW executive board who he and many others felt had become too cozy with the steel industry. His Steelworkers Fightback platform called for greater union democracy, shop floor militancy, protection of black workers’ rights, and the right to strike.

Stout recalls how Local 1397 dissidents favored much of this program—and wanted to rid themselves of local officials “who took our dues money, refused to file legitimate grievances, and were nothing but lackey yes-men for management.” After Sadlowski’s defeat in February 1977, his Homestead supporters formed a “Rank-and-File Caucus” to win control over the USW’s third largest “basic steel” local. They published a shop newsletter, which became, according to Pittsburgh labor educator Charlie McCollester, “a powerful expression of workplace democracy.” With poetry, songs, satirical cartoons, and muck-raking news articles, the newspaper “unleashed the intellectual and artistic side of those who got their hands dirty” working around the open hearths of Homestead.

Overcoming vicious red-baiting and efforts by international union officials to discredit them, Homestead reformers, led by former boxer Ronnie Weisen, won a landslide victory over long-time incumbents in 1979. Under Weisen’s colorful, if sometimes volatile, leadership—and with much help from Stout—Local 1397 became “a fighting organization on behalf of the members.”

[Sadlowski’s] Steelworkers Fightback platform called for greater union democracy, shop floor militancy, protection of black workers’ rights, and the right to strike.

The local’s new, more combative stance took multiple forms. Inside the mill, according to Stout, “workers demonstrated a hundred different ways you could oppose unsafe working conditions and unjust management treatment on the shop floor, with or without a grievance procedure.” In the past, Stout contends that Local 1397 officials had not been aggressive enforcers of the contract. In fact, “while workers filed hundreds of grievances and complaints, mainly about local working conditions and discipline, most grievances would make it to the third step . . . and then just disappear.” After Stout became an elected “griever,” that quickly changed, thanks in no small part to work by members themselves.

Much to the chagrin of Homestead supervisors, rank-and-filers were welcomed into labor-management meetings for the first time. They played an active role in gathering evidence necessary to win grievance and arbitration cases—and they were empowered to argue these cases on their own behalf. More than anything else, Stout’s creative use of the grievance system restored confidence in the union and produced concrete results, in the form of back pay and other financial settlements worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

But such militancy from below could only go so far. Just as Weisen, Stout, and Local 1397 members were rebuilding their local union’s power, U.S. Steel’s corporate restructuring and downsizing put enormous pressure on the USW to save jobs by making major contract concessions. The new local leadership, on the contrary, felt that the threat of job loss could only be countered by building new community–labor alliances away from the shop floor. Local 1397 tried to accomplish this by helping to create the Tri-State Conference on Steel, an “ecumenical coalition” that spawned the Mon Valley Unemployed Committee, which provided direct aid to displaced workers. They also became backers of the Steel Valley Authority (SVA) that worked with Youngstown, Ohio lawyers Staughton and Alice Lynd to force municipalities to use their power of eminent domain to arrest capital flight and maintain local manufacturing under public ownership.

The ensuing campaign utilized not only litigation but also militant protests, press conferences, grassroots fund-raising, bank boycotts, and political action, which included Stout’s own nearly successful run for the state legislature. But it was no easy task trying to work effectively with a sprawling and often contentious network of community leaders, state and local elected officials, sympathetic academics, clergy members, and laid off workers.

This part of Stout’s memoir makes for inspiring but also painful reading. The author experienced much personal and political acrimony due to disagreements over strategy and tactics. One area of contention was relations between Local 1397 rank-and-file caucus supporters and the new leaders they elected, some of whom were not the best team players. In the end, Stout and his comrades were up against external forces too powerful to overcome. Nearly a century after industrialist Andrew Carnegie broke the Amalgamated’s strike at Homestead, the same mill closed for good.

An important takeaway of Stout’s book, then, is that industrial unionism, however militant and democratic, cannot by itself ensure organizational survival amid widespread de-industrialization. Even if Ed Sadlowski and his Steelworkers Fightback slate had been at the helm of the USW, mounting effective industry-wide opposition to mass layoffs and mill closings, it would have been a daunting, probably overwhelming, challenge between 1979 and 1986.

“In the Mon Valley alone,” Stout writes, “over 27,000 U.S. Steel employees lost their jobs” during that fateful period. While the company was scaling down at home, it ramped up steel production abroad. It also shifted investment into profitable new lines of business like oil and real estate. To make “worker-community ownership” and mill modernization economically viable, it would have taken large-scale federal funding, as part of a comprehensive national industrial policy. And, as Staughton Lynd notes in his afterword to Stout’s book, that was not forthcoming from the administration of President Jimmy Carter. It was even less likely after Carter was defeated by Ronald Reagan in 1980, with the help of votes from more than a few disillusioned steel workers.

Instead, Mon Valley towns like Homestead got decimated, and many USW families were uprooted or impoverished by what Charlie McCollester calls an “industrial holocaust.” This experience of “collective suffering and governmental failure engendered a deep working-class bitterness that haunts our politics to this day,” particularly during another presidential election campaign in which the Rust Belt remains a highly contested terrain.

Stout concludes his memoir with an important message for younger activists about the need to “radically restructure unions to meet the challenges of today.” He warns that, “without democracy and the direct day-to-day involvement of their members, unions will not survive the current right-wing, corporate onslaught that aims to dismantle and destroy them.” The dynamics of late-twentieth century capitalism may have rendered the project of labor radicals like Mike Stout impossible at the time, but their socialist vision remains relevant to modern-day efforts to rebuild working-class power. And, hopefully, readers of this book who have picked up that torch will be able to write a happier ending to their own generation’s labor organizing story.

Steve Early has been active as a labor journalist, lawyer, organizer, or union representative since 1972. He was a Boston-based national staff member of the Communications Workers of America for almost thirty years and is a member of the Editorial Board of New Labor Forum. He is the author of four books about labor and politics, including Refinery Town: Big Oil, Big Money, and the Remaking of an American City (Beacon Press, 2018). He can be reached at [email protected].

For more than fifty years, Mike Stout has been an antiwar, union, and community organizer, as well as the last Local 1397 Union Grievance Chair at the U.S. Steel Homestead Works. He is currently president of the Allegheny Chapter of the Izaak Walton League, the oldest environmental conservation organization in the United States. Stout is also a singer-songwriter and recording artist, with eighteen albums and more than 150 songs written and recorded, who has used his music to raise tens of thousands of dollars for a host of social and economic justice causes.