By Arley Sorg

Lightspeed Magazine

June 2020

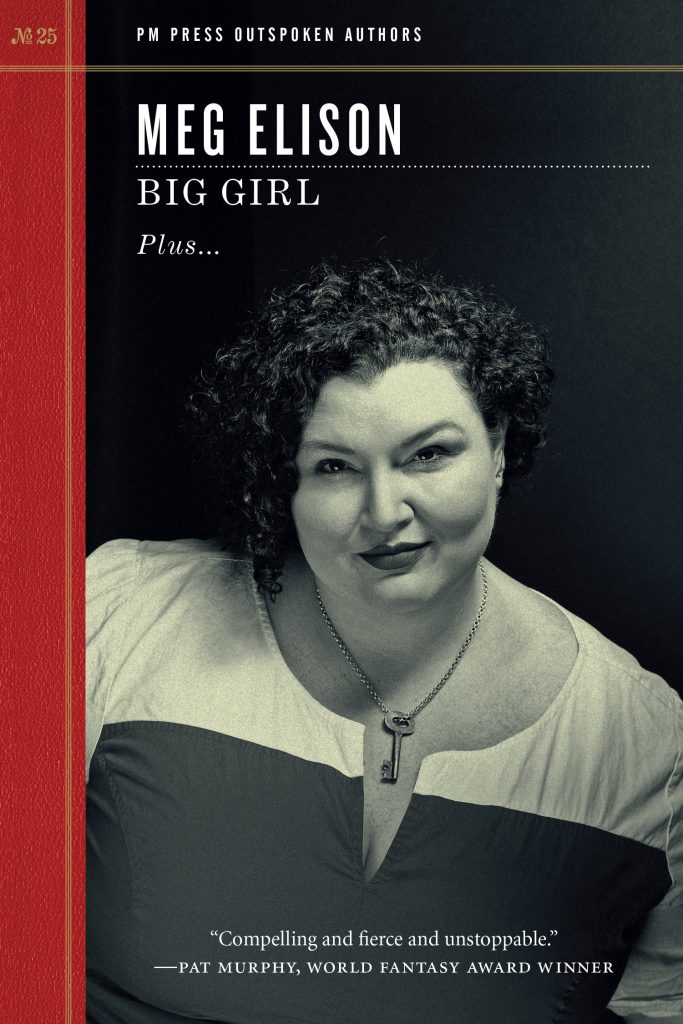

Meg Elison’s Big Girl comprises two original speculative stories as well as reprinted fiction, essays, and an interview with Elison by notable author and Outspoken Authors series editor Terry Bisson. Each piece, including the nonfiction, is immediately arresting, often through an interesting concept or line put right at the front, sometimes through something visual. Sentences are deliberate, composition is careful, and throughout there is an artistry to the writing which, on a craft level alone, is superb. With some pieces more than others, but at least once or twice in pretty much every piece, there are those stunning turns of phrases, those combinations of words which elicit an immediate reaction in the reader, from a smile perhaps, to a surge of excitement, to those moments which make you want to post them on Twitter with trembling hands. Perhaps more importantly than all of this, there is a distinct voice with a clear point of view, one which is sharp, clever, and powerful.

“El Hugé” opens the book, a story about a grotesque, prize-winning pumpkin, and a girl who gets entangled in a mission to destroy it. As an opener it’s a wonderful piece because it showcases Elison’s ability to capture mood and character in brief strokes. The opening line is immediately interesting, and the scene is set with efficient visuals. This story brilliantly embodies the personality of youth, especially frustration and senseless defiance, with a dash of wry humor. Set in the context of the rest of the book, it takes on new, deeper meaning.

Later in the book, Terry Bisson asks Elison if she ever wanted to be small. Her response: “My true form is fifty feet tall and made of gold, shrieking like Godzilla and eating entire oyster beds.” Short story “Big Girl” features a young girl who awakens to find herself huge—around 350 feet tall. She is so big she can’t be properly clothed or fed, and reactions range from hypersexualized to fear. The story is told in a fairly distant third person as well as through media pieces such as newspaper articles, Tweets, and other kinds of posts. On a surface level, it’s just a really cool idea and a fascinating story. But the story works on a number of more meaningful levels. Through exaggeration it examines the dehumanization of the different and especially the female different: among all the reactions, whether fetishizing or wanting to destroy, almost no one bothers to actually talk to the giant, and the tactic of the narrative mostly staying out of her head mirrors this. There is a stunning polemic here against the way we as a culture respond to the strange or the potentially threatening. There are multiple levels of consideration around the male gaze, the selfishness/self-satisfying to the seemingly kind but actually not helpful—such as the faux Times article, which is as much or more about the author and through soft implication how “wonderful” the author is, while serving no real purpose for the girl. In a variety of ways, people enjoy the spectacle of the girl; meanwhile, she is suffering tremendously. Moreover, she is utterly alone. The tale comes to a weird, unsettling, thoughtful conclusion, one which elevates the entire piece beyond what it already does.

“The Pill” might be mistaken as a near-future tale about a new drug which successfully causes rapid weight loss with a fair chance of death (1 in 10). And sure, that’s the premise. But this story is really about the demonization of fat people, on both a sociocultural level and an internalized level; and the absolute loneliness of someone who doesn’t feel like being fat is the evil that everyone else seems to think it is. It opens with the protagonist’s mother, who is so desperate for attention that she routinely enrolls in drug trials, and ends up one of the first to take the pill. The pill works and, despite the potential for death, mom pushes everyone else in the family to do it—the entire family is fat. Mom’s cause and aggressiveness clarifies her motives for the protagonist, who thinks upon a family photo: “ . . . we looked like a basket of round, ripe fruit. I kind of liked it . . . we all looked happy. Happy wasn’t enough, apparently” (quoted material used with permission of the publisher). She sees the urgency for thinness as nothing less than a betrayal, realizing that the things the mother hates are embodied by the things the protagonist is. The speculative element is ramped up as the pill becomes a national phenomenon, and almost everyone is taking it. The narrative then uses the speculative element as a lens to examine the ways in which society rejects and discards fat people, regardless of how any given fat person’s concerns. I won’t spoil where the story goes, because it’s beautiful and brilliant, and it makes me want to read everything Elison writes.

“Such People In It” is another near future piece, this time tracing current political themes to an awful but arguably possible reality. My complaint with this story is mainly in the passive nature of the narrative structure: I would have liked for the protagonist to be trying to do something, to have some goal, some task he’d set out to accomplish. As is, the protagonist is mostly a set of eyes for the reader to experience the world. The eyes have a name: Omar. And, despite my complaint, the story is still very effective. It’s visually striking, grounded enough to feel real, and one section had me absolutely squirming—yet unable to put it down. In other words, it’s still masterful. What I especially appreciate is the variety of elements, from the points which are beat over the reader’s head, to the more subtle aspects requiring more reflection. It all comes to a satisfying conclusion, and feels like the author trying desperately to shake America awake.

Of the nonfiction, “Gone with Gone With the Wind” is an absolute must read. It’s a reflection on Elison’s realizations over rereading the novel Gone With the Wind. It takes the reader on a journey from her youth to adulthood and calls out the ways in which she interacts with the texts, from initially relating as a young girl in its coming-of-age aspect, to interrogating the way the story overlooks—or destroys—the perspectives of the individuals upon which the protagonist’s fortune depends. It’s an honest look at the author’s own biases and position in society, and an argument for self-reflection and the rereading process. In other words, it calls out for people to do better, and it does it by example.

I left this book hungry to read anything and everything Elison writes, not to mention eager to reach out and tell her how amazing she is. There is a wonderful audacity in these pages, as well as a frankness which sets Elison apart from many authors. Elison’s stories kick you awake, enrapture you, and by their end fill you with newly dawning realizations. Her naked honesty is breathtaking; and her skill is unquestionable.

Final Cuts: New Tales of Hollywood Horror and Other Spectacles

Ellen Datlow, ed.

Paperback / Ebook

ISBN: 978-0525565758

Blumhouse/Anchor, June 2020, 480 pgs

Ellen Datlow is one of the most well-known, celebrated, and respected anthologists working today (besides perhaps George R.R. Martin, whose renown is mostly due to works other than his often quite remarkable anthologies). Datlow has been editing since the ’70s, joining Omni magazine as associate fiction editor in 1979 and taking over as fiction editor in 1981. Her first original fiction anthology was 1989’s Blood is Not Enough, comprised of the kinds of stories Ben Bova wouldn’t let her buy for Omni—in other words, horror. She has scores of standalone themed anthologies published, as well as long-running dark fantasy/horror series such as The Best Horror of the Year and the co-edited The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror. She has more awards nominations and wins than most people in this industry will ever see, from a number of award-giving bodies, such as Stoker Awards and Locus Awards, including five Hugo Award wins for best editor. She received a Stoker Life Achievement Award in 2011 for her work in the horror field, and her record-making number of World Fantasy Awards nominations and wins culminated in a Life Achievement Award in 2014. She is prolific: Final Cuts is one of at least three Datlow anthologies scheduled for 2020 release. For many authors, landing in one of her anthologies is as notable as winning an award. She is considered by many to be the foremost expert on horror short fiction.

Final Cuts collects 18 original stories generally around the idea of movies and the film industry. The pieces are by a somewhat diverse collection of voices across intersections of sexuality and ethnicity, though the bulk of the authors are white males; five authors identify as female; but none of the authors are Black. Most of the authors are well-established award-winners and best sellers in horror, as well as a few who are newer but have been recognized as notable, and a few who are well-known authors in genre in general. Christopher Golden, for example, Paul Cornell, Nathan Ballingrud, and so on. What this creates is a body of work which is solid throughout. Everyone in this book knows how to craft a story, they know how to make it cohesive, and in most cases, do excellent work with character and story. Readers could start with nearly any piece and count on finding a good tale.

Many of the stories are similar in that they look back to some specific era and style of moviemaking, and several of them feel less inventive as a consequence, especially when read one after the other. But, one of the most fun aspects of themed anthologies such as this is seeing different approaches to the same idea. In this light, stand outs include “Exhalation #10” by A.C. Wise, which is probably my favorite story in the book. A cop finds a video of a woman’s death in a crashed, abandoned car, and enlists the help of his best friend—who has uncanny hearing ability—to help him find the killer. Nice character details ground the story and give it life, while the overall vibe is perfectly moody, with an effective, continual rise in tension. The combination of brutality and imagery, as well as the tension, somehow reminded me of the movie Seven: a totally messed up narrative which drives you to keep going. At the same time, the brutality never feels gratuitous; it fits the theme and message of the story, and it is integrated into its overall purpose. The final resolution and message of the piece elevates what is already effective horror/thriller fare to make this one of the best pieces in the book. In the ARC (advanced review copy) it’s the third story but I recommend reading it in the middle or towards the end, as a climax to the overall selection.

“Drunk Physics” by Kelley Armstrong is a great addition to the newer movement of internet-based horror, arguably popularized by the 2014 movie Unfriended. Notably, it is also one of the few stories featuring female protagonists. One night at a pub physics doctoral students Trinity and Hannah decide to start an internet show where they get drunk and, only after being drunk, explain physics concepts to the audience. Solid storytelling and a charming voice combine with great interpersonal drama to drive this piece. The characters in this one are among the most relatable in the book, the sorts of people you might expect an author to say, oh yeah, those two are based on these friends of mine.

Laird Barron’s “The One We Tell Bad Children” is a truly remarkable work for two reasons. First, it takes the anthology theme and places it in a fairy tale alternate world which is full of fascinating tidbits of its own accord. Second, it’s written in an over-the-top style, one which, by most authors, would sound stilted and forced, but somehow works very well and provides a smooth fairy-tale read—as long as your vocabulary can keep up. It’s wonderfully dark, and takes the “cursed movie” trope to a different level. I loved the ending, and to be frank, it’s one of the few pieces with an ending which I didn’t entirely predict from the outset.

Perhaps the most truly sinister is “Lords of the Matinee” by Stephen Graham Jones. A man takes his ageing father-in-law to a movie and uncovers a terrible secret. Whereas many of the stories in this anthology draw upon monsters, demons, and the like—or a trip to the movie incites some kind of evil—in this piece, what is truly unnerving is the real, the possible, and Jones uses the speculative element of his story to take the reader there. If the goal of horror is to unsettle the reader, this is probably one of the most successful pieces in the book.

New authors who find success usually have to find it by clawing their way out of a slush pile. Their first few story sales have to stand out immediately, they have to get to the point quickly, and they have to leave an impression upon the reader which lingers. Many venues will have a budget to purchase a handful of original pieces and this is, generally speaking, the only way to make a story stand out in a “slush pile” of hundreds of stories. A side effect of anthologies comprised of established authors is that many of the authors know their stories will be read to their conclusions, and that they will probably be purchased. They don’t have to claw their way to get noticed; they don’t have to make a point quickly. This anthology falls into that category: most of the stories lack the innovation that newer authors hungry to get noticed often bring. All of the stories are “good” but most of them are predictable, and feature a slow build up to an idea reveal, rather than an idea at the beginning which the characters have to deal with, and which (this being horror) causes disaster.

Cassandra Khaw’s story stands out from the batch. “Hungry Girls” grabs the reader immediately with a great opening, not to mention interesting characters and situations. Word choices are cool, style and imagery are striking, and the narrators have a refreshing frankness. It’s about a sleazy low-budget filmmaker taking his motley crew to shoot in Kuala Lumpur and—well. It’s short and to the point and works very well, so I won’t spoil it here.

Richard Kadrey is another author who gets to the point, in “Snuff in Six Scenes.” The piece edges up to torture- or splatter- porn and is a fun example of a more violent sort of horror; not to mention, along with “Exhalation #10,” a testament to the breadth of what we call “horror.” Kadrey shows restraint by letting imagination fill in the actual gory details, focusing on the dialogue and the situation—the shifting relationship between the woman who has come to be killed, and the man who has come to kill her. It’s a clever, short piece.

Many of the stories deserve to be mentioned for one reason or another. “Das Gesicht” by Dale Bailey demonstrates masterful use of language to capture mood and atmosphere. Ballingrud’s “Scream Queen” evolves into something truly creepy, and is among the stories which are thematically stronger, speaking to dreams lost. Lisa Morton’s “Family” ties plot to character nicely at the end, taking the narrative to a thoughtful, interesting place. “Insanity Among Penguins” by Brian Hodge, told in a casual, conversational tone, has great character work, and is a fascinating, thought-provoking existential exploration on the nature of life via concepts of self-annihilation; also—it gets very creepy. “Cut Frame” by Gemma Files has a nice build of intrigue and makes good use of quotes and multimedia excerpts, as well as folklore.

Every story in this book displays a level of skill which speaks to the careers of the authors. Many of the stories are similar in their approach to the theme, but all of them are convincing, and a few demonstrate a staggering knowledge of cinema or horror. There is a reason so many readers place their faith in Ellen Datlow’s taste; and this book is good evidence that her taste has not faltered. It’s a worthy addition to the collection of anyone who loves horror short fiction.

Ring Shout

P. Djèlí Clark

Hardcover / Ebook

ISBN: 978-1250767028

Tor.com publishing, October 2020, 176 pgs

Simply put, reading this book filled me with joy.

In 1922 Maryse Boudreaux and her friends are monster hunters. They hunt Ku Kluxes: demonic creatures who hide amidst the Ku Klux Klan. Chef is an army vet, a big girl with a big knife; and Sadie is a crack shot with a rifle. After slaying a few monsters, they uncover a larger plot, tied to the showing of notorious film The Birth of a Nation. Maryse and her friends must uncover the plot and stop it before it’s too late.

Within just a few lines, I knew I wanted to read this book. At face value this is a great, imaginative dark fantasy adventure story. It’s well-plotted and structured, with enough familiar tropes to be comfortable and accessible, married to enough fresh vision to make it interesting. The escalation and pacing is right on. The monsters are nasty as they should be. Maryse is a wonderful hero, and the people who fill the story are far more than easy plot devices or protagonist accessories. Every character who takes the stage is cool and thoughtfully executed. Everyone pulls their weight and contributes to the story. The narrative is filled with people who are underrepresented, portraying them in ways which are respectful and positive. Real humor is grounded in real culture and relevant discussions, many of which reminded me of conversations I had growing up; all of which is to say the dialogue is great, and it had me laughing.

But what makes this story special is the way it deals with the era and its situations. It opens with Black female heroes taking action and feeling empowered. It focuses on their friendship, their group charisma, their agency. It doesn’t shy away from the nightmarish realities of the time and place: racism, lynching, and so on; and everyone in the story has been personally affected by hate. At the same time, the narrative focus is on strength—and it feels good. This is nothing short of a joyful celebration of Black culture, through music, through language, through stories, through people, through folklore, and more, all in the context of fighting hate and actual demons. It discusses hate and racism with frankness but never lets the negativity of those elements weigh down the story.

This book is also immensely educational in an easy, readable way. The way that the TV show Watchmen created a new nation-wide awareness of the Tulsa massacre, couching it in the context of a narrative in a way which made viewers race to Google to find out more, Ring Shout is deeply researched and rich with information couched in the natural course of the narrative; one can’t but learn while reading it, being entertained all the while, and come away from it edified.

Finally, there’s a thematic conversation around hate, and anger, pain, fear, and related emotions. It’s smart and heartfelt, without being sappy or overly simplistic. It’s an argument for a better way to deal with each other and relate to each other, and it argues by example, making great points.

A smart cultural conversation, awesome characters, empowerment, positivity, and more. Accomplishing so much in such a cohesive, unobtrusive way, while pulling off a solid story with engaging, often really funny dialogue, is nothing less than brilliant.

This book is a gift to American culture.

Arley Sorg grew up in England, Hawaii, and Colorado. He studied Asian Religions at Pitzer College. He lives in Oakland, and usually writes in local coffee shops. A 2014 Odyssey Writing Workshop graduate, he is an assistant editor at Locus Magazine. He’s soldering together a novel, has thrown a few short stories into orbit, and hopes to launch more.

Meg Elison is a San Francisco Bay Area author. Her debut novel, The Book of the Unnamed Midwife won the 2014 Philip K. Dick Award and was a Tiptree longlist mention that same year. It was reissued in 2016 and was on the Best of the Year lists from Publishers Weekly, Kirkus, PBS, and more. Her second novel was also a finalist for the Philip K. Dick Award. Elison was the spring 2019 Clayton B. Ofstad endowed distinguished writer-in-residence at Truman State University, and is a coproducer of the monthly reading series Cliterary Salon.