By Si Dunn

Sagecreek.wordpress.com

June 2nd, 2020

Now more than ever, with some 40 million Americans unemployed, the nation’s economy stalled by protests and a deadly pandemic, and federal leadership failing, we need to review and draw again from hard lessons learned during major events in our nation’s labor history.

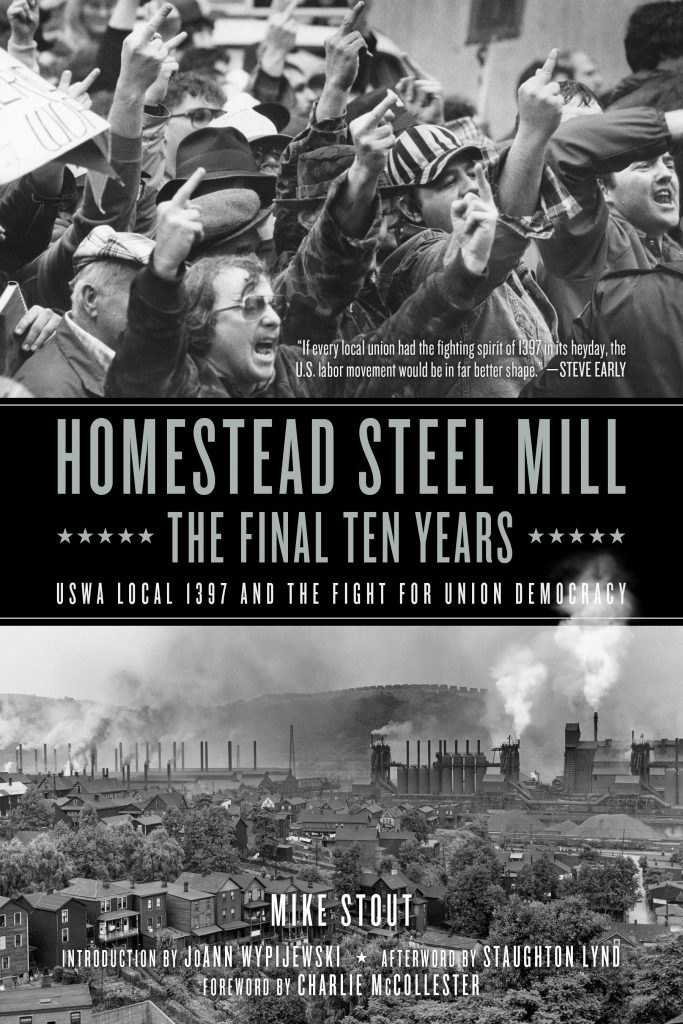

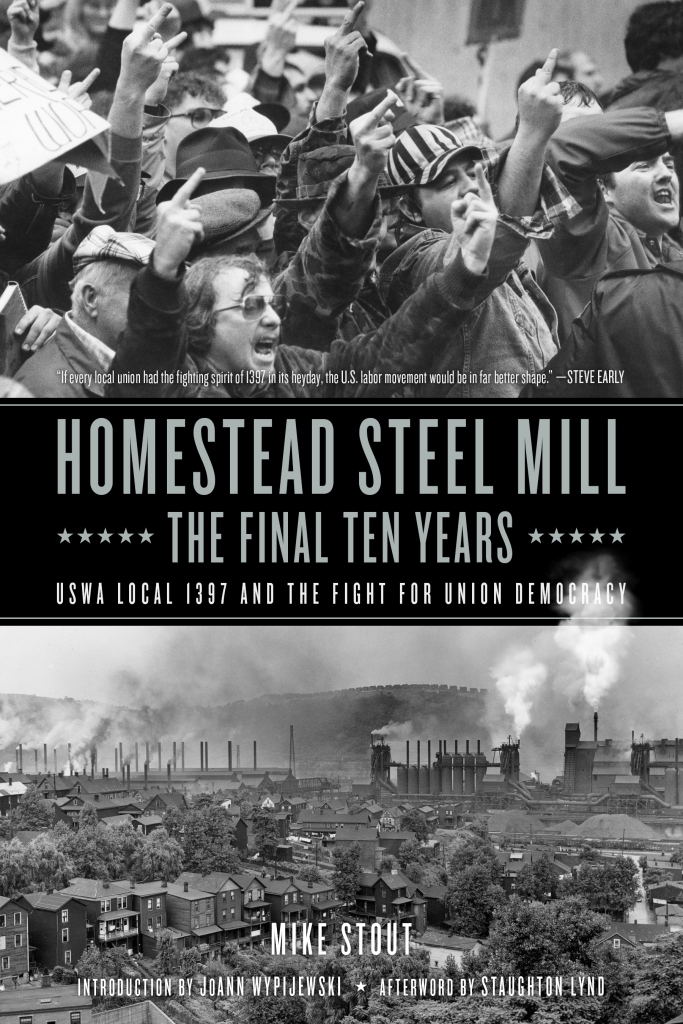

Mike Stout’s well-written new memoir, Homestead Steel Mill: The Final Ten Years,

should be a must-read for labor leaders, labor activists, labor

academics, labor lawyers, and labor specialists at all levels of local,

state, and federal government. It deserves attention as well from

libraries and general readers interested in American labor history, how

unions operate, and what roles unions will play in the nation’s

difficult economic recovery.

The author has walked the walk of a Pittsburgh area blue-collar steelworker and union leader. Stout’s credits are too numerous to summarize here, but include writing for and editing an influential union newspaper, helping found one of the first and largest union food banks, and organizing several community coalitions aimed at trying to help save steel mill jobs. He also is known internationally as a labor and social activist, as well as singer-songwriter.

The Homestead steelworks already had earned a prominent and disturbing place in American labor history when Mike Stout began working there for U.S. Steel in 1978 as a utility crane operator. Indeed, as one of his well-researched book’s sources, Brett Reigh, has noted in a master’s thesis: “In its 106 years of operation, the Homestead Works

[had]

witnessed some of the greatest battles ever waged between labor and capital in the United States.”

In 1892, for example, disputes between the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers and the Carnegie Steel Company exploded into a lockout and then the infamous “Homestead Massacre” that claimed at numerous lives. In an attempt to break the union, Carnegie’s leaders had brought in some 300 Pinkerton guards to try to overwhelm the strikers. A violent battle ensued, and some strikers and Pinkerton guards died. The Pinkertons eventually surrendered, but the strike ended after 6,000 troops from Pennsylvania’s state militia arrived, sided with the mill’s management, and stood guard while strikebreakers were brought in to replace union workers.

Working at Homestead

Mike Stout was one of some 7,000 employees at Homestead and believed he had found a job for life in one of America’s most essential industries. His area also had several other U.S. Steel mills and a total of about 30,000 steelworkers.

In a chapter titled “Homestead–Forge of the Universe, Heart of Industrial Unionism,” Stout recounts some of the Homestead mill’s historical significance:

“Homestead, Pennsylvania, has been synonymous with steelmaking since 1880. For over one hundred years, the Homestead mill, seven miles southeast of downtown Pittsburgh on the south side of the Monongahela River, made the steel that helped shape the Industrial Revolution in America, producing armor plate during America’s involvement in both world wars, as well as the Korean and Vietnam Wars. It made structural beams for skyscrapers, including the St. Louis Arch, the Home Life Insurance Building in Chicago, the Pan Am, Empire State, Rockefeller Center, and United Nations Buildings in New York City, and the shafting for the power plant at the Hoover Dam. It made the steel for every major bridge and waterway back in the day, from the Panama Canal through the Golden Gate and Oakland Bay Bridges in San Francisco out west to the George Washington and Verrazano-Narrows Bridges back east.”

During Stout’s times at Homestead, however, steel mill owners were refusing to modernize and increasingly sending jobs and steel investments to cheaper sites overseas. Many workers, including Stout, were laid off repeatedly and not all were called back to work. As Homestead’s workforce shrank, union leaders and union members continued battling to maintain jobs and benefits and to keep employees as safe as possible in dangerous working conditions.

How dangerous? According to Stout:

“Working in a steel mill was dangerous beyond description. You worked in extreme temperatures. Heavy equipment and machinery were flying all about you. You could be working in front of rolling red hot steel where the temperature in the front of your body was 2,300 degrees, but your back would be freezing. You worked a different time shift every week, working 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m., then 4:00 p.m. to midnight the following week, then midnight to 8:00 a.m. the third week. Also, every week your two days off would change; you’d be off Sunday and Monday, then the next week Monday and Tuesday, etc. Your entire life outside of work was determined by your life in the mill. There wasn’t much time or energy for anything else.”

Union members and leaders also fought among themselves over what was the right balance of “union democracy,” how trade unions are governed–an important focus in Stout’s new book. A key concern of the rank and file (the union members) was that union executives would accurately represent the members’ interests when dealing with, and negotiating with, mills’ executives. Much of Stout’s memoir is devoted to his time navigating and leading some of the inner workings of union activities, politics, and activism. Many readers who have no experience with unions may find these chapters both eye-opening and surprisingly engrossing.

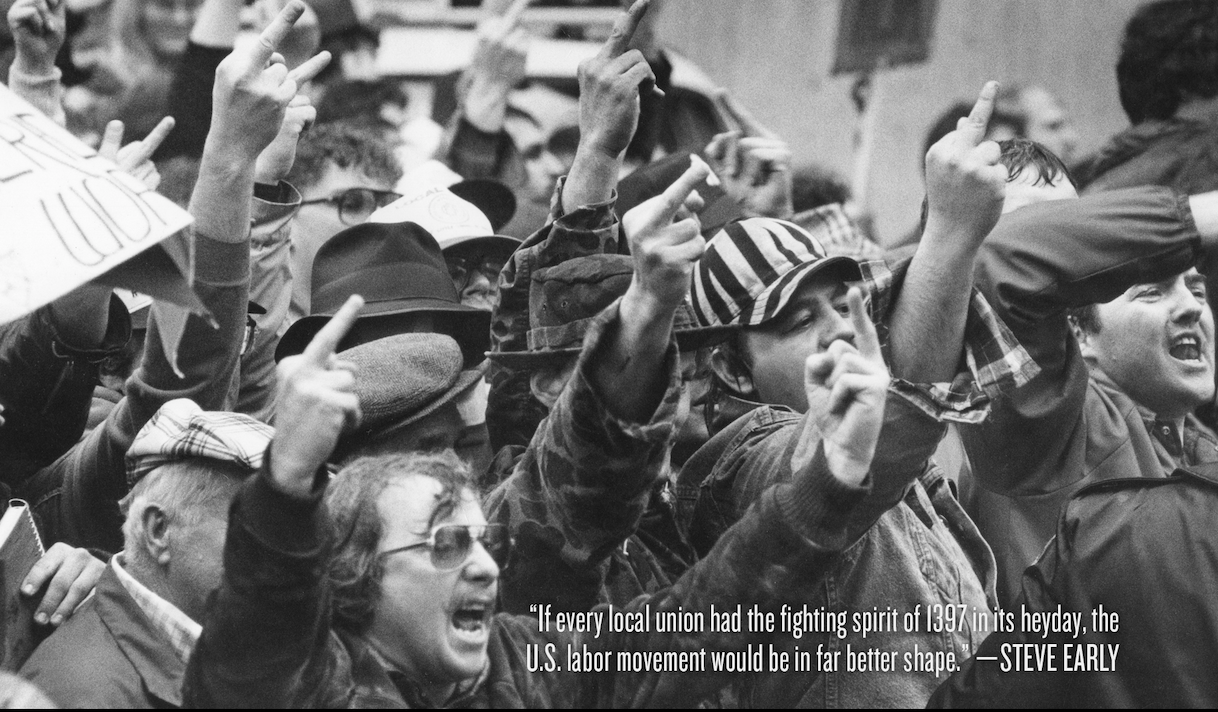

After the plant was shut down in 1987, a shopping mall was built on its site. In a review of Stout’s book, written by a former steelworker at a nearby mill, Mark Fallon recalls: “The union at the Homestead mill, United Steelworkers (USW) Local 1397 and its Rank and File Caucus, was an ‘insurgent’ local that often took vigorous issue with the policies not only of U.S. Steel, but those of its parent United Steelworkers of America International union.”

Fallon adds that while Stout served as the union’s “Grievance Chair for the entire mill between 1981-1987,” he won a significant victory for more than 3,000 former workers: more than $12 million in back pay, severance pay, pensions, and unemployment benefits. “He was the last union official out the door when the mill closed and stayed on for another four years fighting for workers’ pay and rights without receiving a dime from the union.”

After Homestead, What Lies Ahead?

The future of work in America is frighteningly uncertain as this review is being written. In the ongoing pandemic, millions have lost their jobs, businesses, and even careers, while millions of others are now working from home with no certainty that they will have workplaces, positions, or employers to return to in the future.

As Charles McCollester emphasizes in the foreword to Stout’s book: “The coming generation of workers faces a radically changing world of artificial intelligence, robots, drones, pervasive surveillance, genetic engineering, insidious pollution, and accelerating climate change. Mike’s account of a grassroots democratic labor insurgency fighting for economic survival remains relevant, even as the nature of work changes.” (McCollester is former chief steward, UE Local 610, Switch and Signal plant and former professor of Labor Relations at Indiana University of Pennsylvania.)

Stout hopes to see a future where disparate groups unite and create a larger and more powerful social and political force. He urges: “There is commonality in all movements out there—be it Black Lives Matter, the #MeToo women’s movement, health care, immigration rights, worker rights, the environmental movement, or the movements against the many unjust wars our government is waging. Everyone needs a decent job, reasonable benefits, a democratic voice, a healthy environment, equal treatment, dignity, and a peaceful life. Until organized labor joins in a sustained coalition with these movements as one voice, as well as with our elected representatives, we will remain isolated, picked off one by one.”

Steve Early has been active as a labor journalist, lawyer, organizer, or union representative since 1972. He was a Boston-based national staff member of the Communications Workers of America for almost thirty years and is a member of the Editorial Board of New Labor Forum. He is the author of four books about labor and politics, including Refinery Town: Big Oil, Big Money, and the Remaking of an American City (Beacon Press, 2018). He can be reached at [email protected].

For more than fifty years, Mike Stout has been an antiwar, union, and community organizer, as well as the last Local 1397 Union Grievance Chair at the U.S. Steel Homestead Works. He is currently president of the Allegheny Chapter of the Izaak Walton League, the oldest environmental conservation organization in the United States. Stout is also a singer-songwriter and recording artist, with eighteen albums and more than 150 songs written and recorded, who has used his music to raise tens of thousands of dollars for a host of social and economic justice causes.