Credit…Illustration by Joan Wong; Photographs from Getty Images

One lesson from the pandemic: Child care is work. And it should be compensated.

By Kim Brooks

New York Times

May 8th, 2020

Ms. Brooks is a writer.

After just six days of sheltering in place, I found myself thinking about all the women I’d taken for granted.

I started with Griselda, who cared for my kids when they were babies, a few hours each week. I thought about Beth and Perrine, and every babysitter and cleaning lady I’d ever used — all the women I’d paid to come into my home over the past 13 years so that I could leave it and do other things.

If someone had asked me why I paid these women to do things that I could do myself — particularly when I made so little money with the time they freed up — I’d say that I did it because I wanted to work, because I needed to work, not just out of economic necessity but also out of a need to feel like a full human being. The implication here was that when I did the child care and housework and cooking and laundry, it was not work but something else.

Now, for the first time, everyone is doing the work we don’t call work when women do it. We watch Jimmy Fallon play with his daughters while filming “The Tonight Show” and think, “Maybe it’s work, after all.”

The day I turned 16, my father suggested that I get a part-time job. Not just any job — something difficult and monotonous, for little money and less respect. He thought it would motivate me to train for a more remunerative career.

That’s not exactly what happened. I worked as a cashier at a pharmacy, made deli sandwiches and waited tables. But I still majored in English. I came close to applying to medical school, but instead I had a baby, then another. My children’s father made enough to support us but not enough to provide for the child care we’d need were I to return to school or take a full-time job. And so throughout my 30s, I found myself largely occupied with keeping a home and raising my children.

- Thanks for reading The Times.

This work, despite bringing joy and meaning to my life, shared many of the qualities of the menial jobs I’d done before (the changing of diapers, the feeding and cleaning of small bodies, the monotony of dishes). But there was one important difference: The work I’ve done as a mother I’ve done for free.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately, because when the pandemic exploded, I happened to find myself in the middle of a divorce. I would recommend against this timing. If you’ve read the divorce memoir “Eat, Pray, Love,” imagine the exact opposite of that.

I have a lot of thoughts about marriage and divorce, but one is how peculiar it is that it is only through divorce that the work a wife has done as a primary caretaker is given a monetary value. This comes in the form of what used to be called alimony and is now called maintenance. These settlements, the lawyers say, are meant to be “rehabilitative.” I’ve always thought of rehabilitation as a process involving one’s recovery from injury. In this case, the injury is marriage and motherhood.

In our country, staying home to raise children is one of the most devastating financial decisions a woman can make. And without any sort of child care system in place, it’s often not a choice at all. All but the wealthiest mothers face what I’ve come to think of as the Cinderella paradox. Of course Cinderella can go the ball, just as soon as she’s finished her chores.

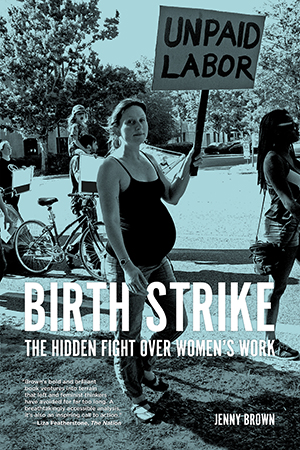

This goes a long way to explain the feminization of poverty. Jenny Brown, the author of “Birth Strike: The Hidden Fight Over Women’s Work,” writes, “Parents, particularly mothers, become poorer because they are not properly compensated for the contribution they’re making to the continuation of society by bearing and raising children.”

What exactly is the value of this contribution? The birthrate in the United States has fallen to a record low of 1.73. People who complain that other people’s children shouldn’t be their concern will still have to deal with the economic catastrophe of an aging population and a shortage of young, healthy workers. If raising these future citizens isn’t socially necessary labor, I’m not sure what is.

And yet our entire economic system hinges on the willingness of women to do this work for free. Caretakers who work outside the home are poorly paid, but those who care for their own kin, in their own homes, aren’t paid at all. They receive a wage of zero dollars and zero cents, no health insurance, no sick leave, no paid time off, no 401(k).

For a long time, I tried not to think about it. One of the ways I was able to not think about it was because I could pay other women to lighten my load. For the time being, those days are over.

Maybe that’s for the best.

In 2012, the Marxist feminist Silvia Federici published a collection of essays, “Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle,” about a largely forgotten movement, the campaign for wages for housework, that began in Padua, Italy, in 1972. Ms. Federici writes, “To say that we want wages for housework is the first step toward refusing to do it.” It makes what’s invisible visible.

In 1972, and in some ways even more so in 2012, the idea of wages for housework seemed radical to most Americans, and counterproductive to many feminists. The liberal-feminist agenda of the past 40 years has been focused on helping women escape domestic burdens and gain reproductive freedom so they can achieve financial autonomy and accumulate power. I have always believed in this project. But on my seventh day of lockdown, I began to wonder if this was exactly where I, and many other white, middle-class feminists, have gone wrong.

Equality will not come from privileged women foisting their exploitation onto other women. Instead women have to say, collectively, “From now on, they have to pay us, because as women we do not guarantee anything any longer.”

In other words, if garbage collectors and grocery store workers and hedge fund managers expect to be paid for their labor, why not those who create and sustain the human race? Why can’t we imagine some form of universal basic caretakers income to support the work mothers (or fathers or other extended kin) do at home?

My favorite expression of this idea comes from Studs Terkel’s canonical anthology, “Working,” in which Jesusita Novarro, a deserted mother of five surviving on welfare, states: “Welfare makes you feel like you’re nothing. Like you’re laying back and not doing anything and it’s falling in your lap. But you must understand, mothers, too, work. My house is clean. I’ve been scrubbing since this morning. You could check my clothes, all washed and ironed. I’m home and I’m working. I am a working mother.”

Whether you’re a nurse, a lawyer, a teacher or a chief executive, if you’re a mother, your relationship to your children and your home has taken center stage in this crisis. There are upsides: more togetherness, more playing, less schlepping, fewer expensive activities of questionable value. But there is also the cleaning, the cooking, the online school. There are arts and crafts. But arts and crafts are messy. More cleaning. More laundry. Who the hell invented slime?

In Covid lockdowns, meetings can go remote and lunches can turn into phone calls and writing can be postponed or done in the middle of the night, but the work of caring for children and our physical spaces doesn’t budge.

As I wrote this, my sweet daughter reminded me that it was almost Mother’s Day. Most of us, married or divorced, rich or poor, will be celebrating the holiday in our homes this year. There will be flowers and pancakes. Everybody likes pancakes. But everybody also likes to be compensated for the contributions they make to the world.

Kim Brooks is the author of “Small Animals: Parenthood in the Age of Fear.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.

Back to Jenny Brown’s Author Page | Back to Silvia Federici’s Author Page