By Cynthia Kaufman

Originally posted on Common Dreams

April 28th, 2020

Michael Moore and Jeff Gibbs’s new film is so full of weak analysis, misinformation, and misplaced invective that I worry it will cause more harm than good.

To me the most misplaced invective is the treatment given to Bill McKibben. He comes across in the film as dishonest and corrupt. And yet he has done more for the climate justice movement than almost anyone else in the world. (Photo: Screenshot)

We are in a climate emergency. That means we all need to do everything we can to get the world to stop burning fossil fuels and chopping down trees. And we need to do it as quickly as possible. Getting to net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 will take everything we have.

That’s why it was so discouraging to see the new Michael Moore and Jeff Gibbs film Planet of the Humans. One virtue of the film is that it calls out greenwashing and challenges the idea that we can sit back and wait for technology to save us. We can’t. Getting to where we need to be requires serious changes in how society operates. It requires massive government investment in a just transition. And it requires that fossil fuel companies and banks be prevented from being the drivers of important social decisions. So, the film’s anti-capitalism is welcome.

But that said, the film is so full of weak analysis, misinformation, and misplaced invective that I worry it will cause more harm than good.

Weak analysis.

Until quite recently in the US, when people talked about climate change, they framed it as something caused by all of us, and to be solved by each of us making different personal lifestyle choices. While there is plenty we can each do, like cutting back on eating meat and flying, that way of framing the issue doesn’t clarify what we are up against and what is slowing the transition.

Bill McKibben, who is severely criticized in Planet of the Humans, kick-started the movement for fossil fuel divestment in 2012 with a speaking tour, and an article published in Rolling Stone magazine: “Global Warming’s Terrifying Math.” The fossil fuel divestment movement’s explicit goal was to pin most of the blame on the fossil fuel companies which spent hundreds of millions on denialism, and even worse, whose business model relies on doing the very thing that needs to be stopped.

Working against that clarity, Planet of the Humans returns to an old-school misanthropic form of environmentalism that blames us all because we are bad as a species. The film starts with some musing on how long humans are expected to last as a species and then Gibbs, the narrator says, “What if a species went too far? How would they know if it was their time to go?” Given the pandemic that is killing so many of our loved ones, that call feels especially wrong right now. There is an ugly history of misanthropy in the environmental movement. One famous example was when some in Earth First said that AIDS was good for the environment.

But we human beings are an adaptable and smart species. We need to use those talents to, as quickly as possible, break some old and dysfunctional habits of ours, like seeing nature as a resource to be exploited for the accumulation of wealth, and allowing those driven by the profit motive to control our political systems.

In addition to his work focusing attention on the role of fossil fuel companies, McKibben has also been a major player in developing a broad multiracial and humanistic way of understanding our situation. According to that climate justice framework, we can live sustainably, even with as many of us as there are, if we dramatically and rapidly reorient our societies toward sustainability. All of the technology and resources we need to do that are with us. But there are powerful entrenched forces keeping us from getting there. As McKibben, and many others argue, the answer is climate justice mobilization, not extinction of our species.

Intellectual Dishonesty

In addition to being based on an outdated and counterproductive analysis, the film is also intellectually dishonest. A person with a 350.org t-shirt at a rally is asked his opinion on biomass. When he says he can’t speak for 350, we are encouraged to think he has something to hide.

Better would be to focus everything we have on making a swift transition away from fossil fuels, deforestation, and the financing of these terrible things.

Solar arrays are criticized for being built using fossil fuels and for having gas hookups as part of their systems. But, so many of our economic processes are wrapped up into the old ways we are trying to move away from, we can’t help but be implicated as we make the transition. Planet of the Humans also used fossil fuels in its making. Gibbs narrates much of the film while driving in a car. I don’t think there is anything wrong with that. The transition is hard and complicated.

The main point of the film is that solar panels and wind turbines can’t work, because making them causes environmental damage, and they cost more energy to make than they produce. It claims that windmills only work when the wind is blowing. Anyone paying attention to these issues knows that getting to functional renewable energy has required a lot of hard work, and some early attempts have failed. There are many people doing life-cycle analysis, looking at the energy required to make, operate, and dispose of renewable energy infrastructure. At this point wind and solar are tremendously successful. And few people besides Donald Trump are still worried that windmills only create energy when the wind is blowing. There are now many working solutions to that problem. Gibbs and Moore surely know that. These claims are simply false. Solar and Wind energy are already tremendously successful at reducing greenhouse gas emissions and their rapid expansion is key for getting the world off of fossil fuels.

Misplaced Invective

Finally, the film is full of misplaced invective. I am ok with the way the film takes down people like Richard Branson, though it left out the juiciest fact, that after getting a lot of press for promising to donate $3 Billion to the climate crisis, he never did so. And yes, we should remain skeptical of the work of people in finance who are engaged with climate change work. And yes, there is fraudulent pro-corporate greenwashing everywhere.

A film that really took that on, with enough credibility for its claims to be believed, would be helpful. But given how untrustworthy the film is, I have no idea if the Sierra Club compromised its principles in the investment companies it promotes. I know that its Beyond Coal Campaign was enormously successful, and that, as much as I dislike Michael Bloomberg, he played a very positive role in it. I’m not a fan of the corporation Caterpillar. But the fact that its bulldozers were used against protesters at Standing Rock doesn’t make me against bulldozers. And it does not make me criticize the Sierra Club for being associated with investments in Caterpillar.

To me the most misplaced invective is the treatment given to Bill McKibben. He comes across in the film as dishonest and corrupt. And yet he has done more for the climate justice movement than almost anyone else in the world. For all I know he has made some mistakes in the past and backed some initiatives that turned out to not be good ideas. I have no idea. But the way he is presented in the film is pure propaganda. Look at the claims critically, even without having any outside information, and they all turn to smoke. Why Gibbs and Moore want to take down McKibben is a mystery to me.

What we need to accomplish as a species in the next ten years is almost impossible. The chance that we stabilize at the minimally safe level of 1.5C level of warming is vanishingly small. Anyone with the resources to make films about the climate crisis should think seriously about how their work will help motivate people to do everything they can to join the movement and do all they can to make a difference. The time for musing on whether or not it might be best for us as a species to die out is long past. Also long past is the time when we can be a circular firing squad and take down some of our most impactful leaders and organizations.

Better would be to focus everything we have on making a swift transition away from fossil fuels, deforestation, and the financing of these terrible things. Better would be to focus on helping people understand how they can become part of the rising climate justice movement and throw everything they have into making the planet remain habitable for our species and for others. I’d rather do that than sit back and wonder if we should all die.

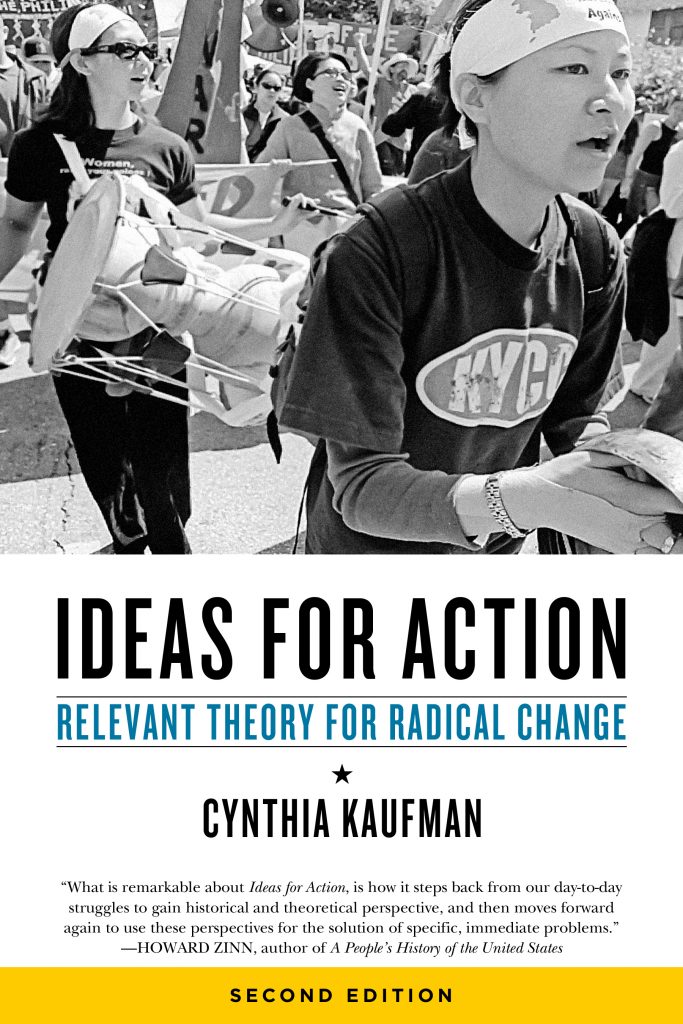

Cynthia Kaufman is the director of the Vasconcellos Institute for Democracy in Action, where she also teaches community organizing and philosophy. The author of Getting Past Capitalism: History, Vision, Hope (Lexington Books, 2012), she is a lifelong social change activist, having worked on issues such as tenants’ rights, police abuse, union organizing, international politics, and most recently climate change. Her books include Ideas for Action: Relevant Theory for Radical Change, 2nd Ed, Challenging Power: Democracy and Accountability in a Fractured World, and The Sea is Rising and So Are We: A Cliamte Justice Handbook forthcoming PM Press 2021.

Back to Cynthia Kaufman’s author page