May You Live in Radical Times

By Jeff Sparrow

Sydney Review of Books

March 23rd, 2020

‘My friends […] my friends, is there any one here – any soul brother among you – who doesn’t know my name, what I’m called? So you all know it, do you? […] Then say it, friends and soul brothers, say it!’

And the crowd cried, ‘Panther, Panther!’

‘That’s right, cats. That’s right. I’m the greatest panther in the jungle.’

The passage comes from an obscure piece of fiction entitled Panther Jones for President. The 1968 novel details the rise of the titular Jones – a character described as an ‘architect of Black Power’ – as he ensconces himself in the White House, concludes the Vietnam war, and restores moral legitimacy to America.

The book’s author, a certain Stanley Johnson, later became a Conservative MP – but he’s better known today as the father of the current British Prime Minister.

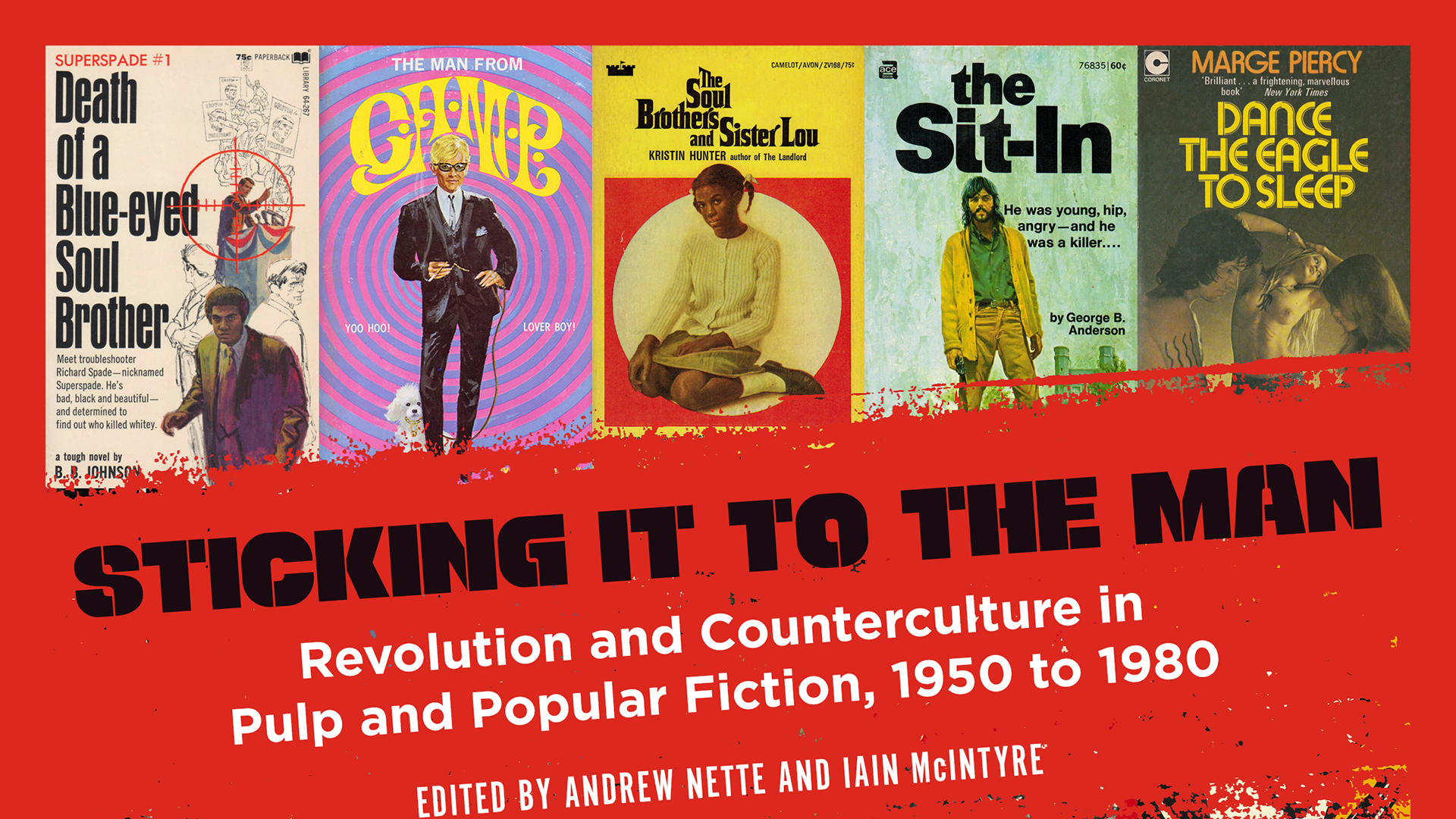

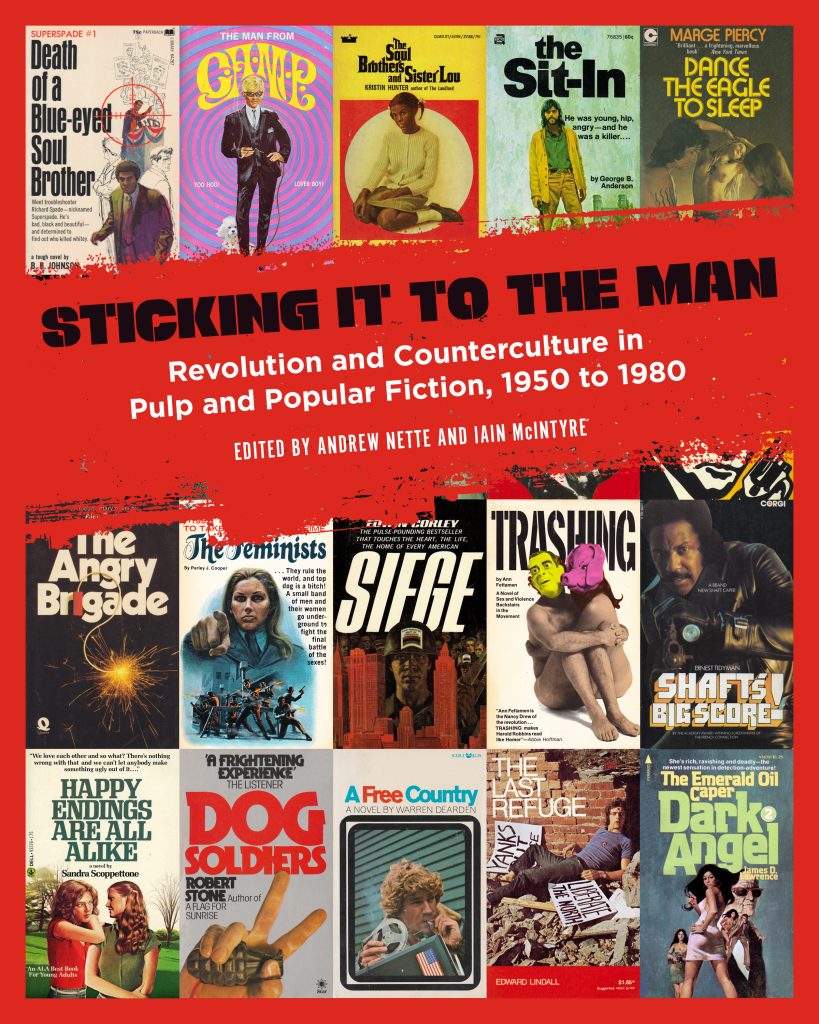

Given Boris Johnson’s notorious remarks about ‘piccaninnies’ with ‘watermelon smiles’, we might be startled to discover Stanley – still a staunch Tory – enthusing about a black militant leading a crowd in chants of ‘Kill, panther kill’. Yet, as Andrew Nette and Iain McIntyre show in Sticking it to the man: revolution and counterculture in Pulp and Popular fiction 1950 to 1980, market writing dealt with sixties radicalism in contradictory and often bizarre ways.

Nette and McIntyre describe their edited collection of writings by scholars and enthusiasts as an incomplete history of fictions produced in the United States, Australia, and the UK during – and in response to – the so-called ‘long sixties’: that period of social and cultural change that can be extended conceptually until the mid-seventies.

Some of these books sold in astonishing quantities. The name ‘Don Pendleton’ might not resonate with SRB readers yet his ‘Executioner’ novels – ‘men’s action adventure’ stories about anti-Mafia hitman Mack Bolan – have moved more than two hundred million copies.

Yet we can only describe Sticking to the Man as a survey of ‘popular’ fictions if we acknowledge the delight its essayists take in obscurities. Brian Greene, for instance, concludes his piece on the black pulp writer Robert Deane Pharr with a reference to a novel supposedly entitled The Welfare Bitch. He concludes, somewhat mournfully, ‘I have not been able to find evidence that this book actually exists’.

That desire of a collector for completism exemplifies the cult around pulp, a cult that (at least in part) inverts conventional literary hierarchies. In his chapter on ‘Pulp Fiction and Campus Revolt’, Brian Coffey enthuses over John Post’s novel Campus Rebels (1966), one of the many rightwing fictions about insurgent students. Like most of the authors cashing in on prurient curiosity about radical campuses, Post portrays his undergraduates as dupes of others (in this case, ‘honey pot agents’). In thrall to sinister notions of freethought and free love, the nineteen-year-old Ralph shaves off his beard, embraces perfume, and begins wearing women’s lingerie; the eighteen-year-old Judy becomes a lesbian.

‘Part of the charm of Campus Rebels’, Coffey explains, ‘if that is the correct word, is that the production is low-rent: about 45 of the 160 pages are blank; there are a number of spelling mistakes, and some sentences are repeated. All in all, it was well worth the 95-cent price tag on the cover.’

As Nette and McIntyre say, such books constitute ‘fascinating curios’, artefacts valuable ‘despite, or more often because of, their blunderingly bad dialogue, woefully inaccurate “hep” patter, erratic plotting, and lack of continuity’.

But Sticking it to the man also invites a reappraisal of traditional aesthetic judgements in ways that extend beyond the ‘so bad it’s good’ argument of the pulp aficionado.

Danae Bosler writes of Betty Collins, whose 1966 The Copper Crucible provides a rare example of an Australian industrial novel. Collin describes a union struggle against the Mt Isa Mines Company; she also explores, in terms inspired by sixties radicalism, the ethnic and sexual divisions of a mining town in conflict. Bosler quotes Ian Syson (who championed the book’s republication in the 1990s) on The Copper Crucible’s neglect, which he attributes to politics cloaked in the lexicon of aesthetics.

In The Australian, for instance, the reviewer Frank Stevens dismissed The Copper Crucible on the basis that Collins had ‘not fully exploited her craft’; in the Age, Tom Healy assessed the narrative as ‘competent as far as it goes, which was not far enough’.

Neither man acknowledged the reason why Collins didn’t ‘go further’: her publishers, fearing reprisals by one of the most powerful corporations in the country, had cut 25,000 words out of an already short novel, rendering it almost incomprehensible. A supposed artistic failure pertained, in other words, directly to politics and the conditions under which her politics could be expressed.

By necessity, the texts studied in Sticking to the Man encourage a critical materialism. You can (or, at least, people do) write on canonical literature while saying nothing about the industrial infrastructure of that literature. But you cannot analyse the Mack Bolan books without recognising Pendleton’s deal with Gold Eagle, which, after buying the rights to The Executioner, set a team of industrious ghost writers (Wikipedia lists some 70 of them) to churn out his adventures (now numbering more than 400 books).

An understanding of commercial fiction requires, in other words, an understanding of commerce. As Nette and McIntyre suggest, the long sixties coincided with the paperback boom, which primed certain genres for the exploration of the previously taboo.

[B]ecause paperback publishers put out more titles and often paid better rates than their more highbrow competitors, this allowed a growing number of authors to make it into print, if not sustain a comfortable living. […] Alongside [the] major firms, smaller outfits eked out reasonable profits through the production of pornography and genre fiction. Much of their output represented pale imitations of the books their bigger rivals were producing, but some of it was superior due to their propensity to take a chance on something different or unusual.

In his chapter about gay pulp, Michael Bronski explains that such publishers provided space for writing dealing with homosexuality, even before a series of landmark free speech trials (Howl, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Tropic of Cancer, etc.) turbocharged the erotica market, so that ‘new companies published hundreds of titles every month, which became readily available in a variety of venues’.

Many of the books containing homosexual sex were not ‘gay novels’ in the way we might think of that term today. Nevertheless, they performed an important pedagogical function for gay men, allowing them to recognise themselves and to understand ways they might live.

‘Most of this knowledge [was]’ says Bronski, ‘filtered through the lens of art and storytelling – bounded also by the pressures of the marketplace – but it was useful information for those who needed to know’. Alley Hector makes a similar case about what she calls the ‘lesbi-pulp’ novels, books that chronicled (as one publisher put it) ‘the love that smoulders in the shadows of the twilight world’.

Such fictions were moneymaking ventures and often marketed to heterosexual men, with covers depicting stereotypically-attractive women as if seen through a keyhole, an implicit invitation to the voyeuristic male. Yet, because they sold in drugstores (‘right across from church and school’), they offered an accessible gateway to a different sexuality.

The academic Michele Barale suggests that lesbi-pulp enabled both men and women (even heterosexual men and women) to imagine more fluid gender roles. The books might have been commissioned by straight men wary of portraying lesbianism too sympathetically but they were written by women, who could use them for different purposes. Lesbi-pulp author Lora Sela (who wrote as ‘Carol Hales’) later said, ‘I agreed to give [the publisher] overt sex scenes if he would allow me to get my own propaganda over – to gain understanding and tolerance for Lesbians’.

The novels thus served a political function for readers (or some of them, at least), providing a vocabulary that same-sex attracted women could adopt and adapt.

‘[T]he lesbian paperback was … an important tool for the individual’, concludes Hector. ‘It was a piece of accessible literature that suggested not only that there were other lesbians out there but that, although a lesbian life may be difficult one, it could also be a happy and sexually fulfilling one. It made the idea of living as a lesbian possible where it had not even been imaginable before.’

These examples suggest a complexity that the contemporary politics of identity often elides. One struggles, for instance, to apply notions of ‘appropriation’ to fiction so overtly based on commodification. For example, in 1967, an African American writer calling himself ‘Iceberg Slim’ published a book entitled Pimp. After riots in Watts in 1965 and Detroit in 1966, Pimp’s bleak depiction of black urban life struck a chord: the subsequent Trick Baby appeared with the cover blurb lauding ‘America’s most read black author’.

Iceberg Slim wrote frankly about subjects – crime, drugs, sex work – that many literary authors preferred not to address, in texts buttressed by the authority of lived experience (Pimp was subtitled ‘The Story of My Life’). But, as Kinohi Nishikawa notes, the Iceberg Slim who approached Holloway House with his first manuscript was known to most people as Robert Beck, a ‘middle-aged door-to-door exterminator’.

Beck had, indeed, been a pimp, developed a cocaine habit, and spent time in prison. Essentially a small-time ex-con, he developed the over-the-top persona in his writing as a carefully curated performance. ‘[H]e embraced’, says Nishikawa, ‘the fiction of Iceberg as a strategy of building his literary mythos’.

Paradoxically, the commercialism of pulp facilitated such ‘literary’ strategies. A more respectable publisher might have required fidelity from a supposed memoir. But street titles were an entertainment, with readers treating their claims to facticity as they would any other advertising puff: not necessarily false but definitely not true, either.

A comparison of Pimp, a depiction of ghetto suffering, with the slightly later Shaft, a novel evoking ghetto militancy, illustrates how the industry capitalised on the changing times. The book introduced the character John Shaft: a detective hero both hip and tough, described by the novelist Nelson George as one of ‘the only black superheroes we knew’.

Yet, where Beck mined his own life for the Iceberg Slim mythos, Shaft emerged from an even more deliberate appropriation by a former journalist called Ernest R Tidyman, described by a contemporary as a ‘very WASP-y person from Ohio’. Tidyman had, in fact, first tried to capitalise on the hippy phenomenon (with a failed novel called Flower Power) before pitching Shaft to Macmillan in 1970 after hearing that editors there sought black material.

Does that render Shaft less ‘authentic’ than Pimp? In many ways, the question doesn’t really make sense. The African-American composer and pulp writer Joseph Perkins Greene once joked that he published his very Shaft-ish ‘Superspade’ books (’He’s bad, black and beautiful …’) under the moniker BB Johnson, ‘in case I get tired of writing the books and they hire someone else’. The quip reflected the reality of an industry in which romantic notions of authorial genius mattered less than sales, with publishers quite prepared to ‘hire someone else’ as required.

John Shaft became iconic precisely because of Tidyman’s commercialism: his willingness to shop his idea for a film deal even before the first book appeared. The ensuing 1971 MGM movie established the briefly flourishing ‘blaxploitation’ genre, with its success retrospectively changing the meaning of Tidyman’s character.

‘While Shaft had a huge influence on the big screen and popular culture’, writes Steve Aldous, ‘it was much less so on the written page. Blaxploitation was a heavily stylised visual and sonic experience that demanded the cinema as a medium. John Shaft on the written page was merely another detective …’

The cultural significance of Shaft depended, we might say, less on Ernest Tidyman and more on Isaac Hayes. Or, more exactly, it depended MGM and its willingness to utilise whatever talent (whether black or white) necessary to capitalise on an emerging new market.

The connection between pulp and hip hop (a relationship noted by several contributors to Sticking it to the Man) illustrates how capitalism simultaneously fosters ideas of cultural ownership even as it strips them of all real meaning. Both Ice-T and Ice Cube styled themselves after Iceberg Slim; Jay-Z, at one stage, performed under the name of the Pimp author. Jay-Z, 2Pac, Nas, Ludacris, and many others cited the work of Donald Goines, another seventies pulp novelist writer who, like Slim, wrote about drug addiction and sex work.

The influence of such figures extended to politics.

In books like The Naked Soul of Iceberg Slim, Slim argued that capitalist America had emasculated African American men. They had, he said, been ‘deballed’, reduced from the dominance of the pimp to the submission of the whore. On that basis, Slim insisted he had ‘gained wonderful new ball power from the courage and daring exploits of the Black Panthers’, a description that transformed the freedom struggle into a campaign for masculine restoration.

At the height of the early nineties controversy about gangsta rap, Ice-T, in particular, used similar claims to defend tracks like NWA’s ‘One Less Bitch’. If Dr Dre depicted himself murdering a sex worker for withholding money, his performative misogyny was, the argument went, an expression of racial militancy, derived from the reality of ghetto life.

The connection between political consciousness and aggressive heterosexuality ran through much of the African American pulp of the seventies. Hayes’s ‘Theme from Shaft’ (with its celebration of ‘the black private dick that’s a sex machine to all the chicks’) made a similar equation between radicalism and male sexual potency, as did the ‘Superspade books’ (in which, as J Kingston Pierce tells us, Richard Spade’s sweat contains ‘a musk with an aphrodisiac quality irresistible to the opposite sex’).

Yet, as Bill Osgerby points out, this was a white argument as much as a black one, with the counterculture in general containing a ‘rich vein of macho chauvinism’. By way of example, he describes The Shards of God, a 1970 novel by Ed Sanders (the sometime frontman of The Fugs) in which Yippie leaders Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin feature as sexual athletes, their stamina distinguishing them from the emasculated men of the square world.

In his Street Players: Black Pulp Fiction and the Making of a Literary Underground, Nishikawa argues that the sexual politics of black pulp can, in fact, be traced back to the distinctive blend of misogyny and libertinism that marked American men’s magazines in the 1950s: publications that appealed to white male fears of suburban domesticity eroding masculinity.

Holloway House (the publisher of Pimp) initially presented its books to the same audience, offering Iceberg Slim to white readers as a racialized caricature, a vehicle for suburban fantasies about the unbridled sexuality of the black street. Later, as the ‘Blaxploitation’ fad kicked in, the company switched from ‘white sleaze’ to ‘black sleaze’ – but the subsequent development of a genuine African American readership for such texts pertained less to their ‘authenticity’ than to Holloway House’s ability to read markets.

In that sense, rather than representing either reality or radicalism, the misogyny adopted by some gangsta rappers could perform a familiar commercial function, helping them reach an audience of white male teenagers attracted to cartoonish fantasies.

But that’s only part of the story.

Yes, the counterculture contained strands of unabashed chauvinism. But the sixties upsurge – of which black liberation, women’s liberation and gay liberation were integral components – also transformed the sexual and gender possibilities available to millions of people.

Many of those people wanted a new culture, one that celebrated freedom rather than oppression. Bronski writes, for instance, of how the older pulp literature was suddenly seen as a hopelessly compromised by a generation of activists craving liberatory writing.

To create a new culture they built a new infrastructure, with, as McIntyre says, the bulk of the radical feminist, gay and lesbian books published in the early seventies emerging from independent small presses, supported by radical bookshops, distributors, and organisations.

He describes the success of Rita Mae Brown’s Rubyfruit Jungle (1973), a lesbian coming-of-age novel fundamentally different from the earlier ‘lesbi-pulp’: a book that ‘distilled the rapid social changes of recent years [and] featured the kind of plucky and vivacious character a variety of audiences could relate to, cheer on, and want to emulate’.

Brown’s novel was facilitated by Daughters Incorporated, a relatively well-resourced alternative press. But, McIntyre says, the company’s success exacerbated internal tensions, divisions between those who saw the venture as a radical intervention run by lesbian feminists and those who wanted to compete with the mainstream as a publisher of women’s writing.

Even the most idealist publishing co-operative could not escape the conflict between principle and profit. Melbourne’s small and short-lived Gold Star Publishing provides an illustration of how completely the two might become entangled. Gold Star developed out of a venture run by businessman Gerald Gold, who’d been buying remaindered books from the southern UK as job lots, importing them sight unseen by the containerload, and then retailing them cheaply in Australian newsagents.

As the censorship laws changed in the late sixties, Gold re-oriented to the very lucrative ‘adult oriented’ titles, including softcore porn magazines. In 1972, his son Geoffrey, a sometime member of the Maoist-dominated Monash Labour Club and the Worker Student Alliance, convinced his father to invest these windfall profits in original content.

Gold Star’s most successful titles included local author Wal Watkins’ Wayward Warriors, a book about homosexuality in the navy; The Quiet Revolution, by former deputy prime minister Jim Cairns; and the Australian version of The Little Red Schoolbook, a frank-speaking sex education tract for young people that became a cause celebre when radicals distributed it outside schoolyards.

‘My father didn’t have a clue about that book, even though he was financing it’, Geoffrey Gold says in an interview with Nette. ‘That was a battle I was happy to play. It was straight politics.’ Yet Gold Star’s list also contained Edward Lindall’s The Last Refuge, a thriller by a conservative journalist about an Australian Security Intelligence Organisation agent bringing down a group of Maoists waging guerrilla war in the Northern Territory.

Why did Gold publish that? His explanation for accepting the novel A Different Drummer by Don Crick provides a hint. ‘It was an anti-war book that no-one would publish,’ he says of Crick’s novel. ‘I didn’t think it was that good. It was pretty turgid, but I had a machine to fill, so I took it and also his other books …’

On the same basis, Gold bought the paperback rights to other titles originally published by the Australasian Book Society (a venture associated with the Communist Party of Australia). As a result, earnest social realist novels by Judah Waten appeared in newsagents tricked out in lurid pulp covers – until a state crackdown on ‘girlie magazines’ drove the whole venture into insolvency.

The vignette provides illustration of the obvious difficulties in the production of anti-capitalist literature under capitalism, a system that takes any limit as merely the basis for a new round of accumulation.

The internal contradiction implicit in such a project means a radical cultural infrastructure become very difficult to sustain without mass movements – and, of course, from the mid-seventies, the mass movements began to wane.

In 1985, the British writers Charles Landry, David Morley, Russell Southwood, and Patrick Wright published a book called What a way to run a railroad: an analysis of radical failure, drawing on, as they put it, ‘our experiences of working in the alternative/radical press, in publishing, in libertarian and community politics, and in the voluntary sector over the last ten years’.

Their book described the collapse of radical literary projects remaining from the sixties:

Among the radical organisations and publications which have closed down or disintegrated into inactivity over the last few years are: Achilles Heel, Agitprop, Anarchist Library, Anarchist Workers Association, Anticircus, The Beast, Beautiful Stranger, Bethnal Rouge, Black Liberator, Black Phoenix, Bogus Books, Brixton Boss, Case Con, Captain Swing, Cinema Rising, Crann Tara, Creative Mind, December 6tj Group, East London Gay Liberation Front, Educational Libertarian Network Enough, Fightback, Freewheeling, Gay Left, Humpty Dumpty, Index Books, Inside Story, Islington Socialist Club, LASH, Last Exit, The Left Centre, The Leveller, Libertarian Education, Lunatic Fringe, MS Print, Musics, Nell/Ned Gate, New from Neasden, News Release, On Yer Bike, Orwell Books, Outcome, Penny Black, Peoples News Service, Prompt, Radical Education, Red Rag, Rising Free, Fourth Idea, Scarlet Woman, SCARP, Seeds, Shrew, Slate, Solidarity for Social Revolution, South London Socialist Club, Spice Island, Spinster, Stage One, State Research, Temporary Hoarding, Toolshed, Teachers Action, Ultima Thule, Unemployed Workers Union, Up Against the Law, Undercurrents, Voices, Wedge, Whole Earth, Wild Cat, Women’s Action, Women in Action, Womens Liberation Workshop, Women’s Report, Xtra, Zero, Zig, and, in addition, innumerable community newspapers in different parts of the country.

From the perspective of 2020, that list seems remarkable not from the amount of organisations winding up but rather from the sheer number that existed in the first place. Certainly, a comparable survey of radical publishers, booksellers, and media outlets operating today in the US, Britain or Australia would make for a grim – and much briefer – read.

The sixties’ struggles – like mass movements anywhere – contained contradictions, including reactionary ideas ripe for exploitation. The new readers created by the upsurge generated a market for Rita Mae Brown but they also provided an opportunity for opportunists like Stanley Johnson to present the civil rights struggle in terms of white America getting its groove back.

With the decline of the movement – and the organisations it enabled – radical culture became much harder to sustain, while overtly reactionary ideas (such as the equation of misogyny and rebellion) could more easily be identified themselves with the legacy of the struggle.

In the context of the now more-or-less complete collapse of the New Left, the pulp novels of the fifties and early sixties deserve reconsideration, since, in some ways, contemporary pop culture today occupies a similar space, in that it’s produced almost entirely by commercial businesses with no relationship to any real social struggle.

As we’ve discussed, the crass, exploitative (and sometimes homophobic) erotica churned out by pulp outfits could play an important role in the lives of gay men in the early sixties, irrespective of the publishers’ intentions. Likewise, the authors writing ‘lesbi-pulp’ could bend the genre in conscious political interventions that made their novels significant to other women.

In other words, the cultural products of that era mattered to oppressed people, just as much – or perhaps more – as comics, songs, movies, and video games mattered to people today.

Yet what would the critical apparatus typically deployed by progressives today to analyse pop culture have offered consumers of Stranger on Lesbos or (the gay cowboy novel) Song of the Loon? No doubt some would have appreciated greater diversity or more representation or simply fewer endings in which protagonists converted to heterosexuality or died lonely or miserable – even if so much of the literature was was interpreted against the grain, with readers finding their own meanings in texts not even intended for them in ways that challenge some of more naïve theories about the function of representation.

At the same time, the experience of the period shows the clear limitations of challenging pop culture within the space of pop culture. That is, the publishers churning out erotica read by gay men did not care about gay men. They cared about making money, just as the corporations behind pop culture franchises today care about making money.

The astonishing transformation of the literature available to queer readers in the late sixties did not, then, rest upon a critique of characters, themes or narratives (although such critiques did eventually play a part). It rested upon pitched battles with police at a gay bar in New York in late June and early July 1969.

The Stonewall Riots, and the gay liberation movement that it spurred, changed everything, re-shaping the contents of books by utterly re-making the industry – indeed, the society – on which they depended.

We do not live in radical times. Today, the Man more often sticks it to us rather than the other way around. Yet that makes Nette and McIntyre’s book all the more important, as a reminder of how social structures that seem frozen in place can, all of a sudden, melt and change.

For those of us who work in culture, the history they document should inspire us to lift our ambitions. If we want to change the books we read, we should endeavour to change the world that creates them.