By Anne Hogenson

Ferris Magazine Online

In 2015, David Pilgrim and Franklin Hughes, of Ferris’ Diversity and Inclusion office, began a small research project to celebrate the first African-American student to attend Ferris State University. At the time, they believed this to be Gideon Smith (graduated 1912), who went on to become the first African-American varsity athlete at Michigan Agricultural College (now Michigan State University).

What Pilgrim and Hughes uncovered will change how many people understand Ferris’ history. They spoke with me on April 3 about their research and the book they are in the process of writing on it.

Anne Hogenson: What do readers need to know to give context to the story you and Franklin have to share?

David Pilgrim: Our book starts out with me talking about a mural which is in the Arts and Sciences Commons’ atrium area. In the late 1990s, campus artist Robert Barnum was tasked by the university to create a mural to represent the history of Ferris. If you look at the mural, it’s in some ways very good, but there is only one person who is identifiably black in it. I taught sociology here for 17 years, and I spent a lot of time in that building, so I saw that mural every day. It’s easy for me to criticize it now because I know a different story, but Barnum painted the story that he knew. Back then, it was the story that we all knew. However, what we’ve since discovered through our research is a different story, that there were many African Americans who were here in the early years of the university, and many of them left and did great things.

Once I took this current job as vice president of Diversity and Inclusion, I noticed around our campus there were not many representations of people of color in campus artwork. I thought one thing we could do was go back to the person whom most of us agreed was the first African American here, Gideon Smith, and do something to celebrate the fact that he was here. I asked Franklin Hughes, who works in our office, to find an image of Smith. That started him looking through old yearbooks and the Internet, and he uncovered a great story—or, to be more accurate, several stories.

AH: Franklin, you went looking for a picture of Gideon Smith, but I gather you found much more?

Franklin Hughes: David tasked me to find some images of Gideon Smith, so I started looking through yearbooks, and I noticed right away that there were a couple other African Americans. I showed David, and he said “Who are these guys? If they were here at the same time as Smith, then maybe he wasn’t the first.” I was always fascinated with the fact that Smith was from Hampton and thought, “Why is this guy from Hampton, Virginia, up here at Big Rapids?” The answer to that eluded me and, in a sense, still eludes us. We have some theories and ideas about what we think could have happened, but there’s not really a substantive, concrete answer.

As I started looking at some of these other guys from the yearbooks, I went to Hathi Trust, an online database, and digitized copies of [Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute’s] magazine, Southern Workmen. There were rolls of the students who were at Hampton, so I started to look and found that some of these individuals who were here at the same time as Smith also went to Hampton. When I started looking at Ferris yearbooks from a little later on, after 1916 and 1917, they would write the person’s name and hometown. And most of the African Americans would be from Virginia. And I thought, “Wow! This is something.”

AH: And that “something,” you were finding, was that founder Woodbridge Ferris appears to have launched an effort that brought dozens, maybe hundreds, of African-American students from Hampton Institute to Ferris Institute to study, from the 1910s through the late 1920s. Why would those students have come to Ferris to study, and why would Mr. Ferris have taken that initiative?

DP: At that time, there were many schools in the South that, if you were an African American, you could not attend. Most of the students that we’ve identified were born, lived and died during the Jim Crow period. Jim Crow was their life, and it limited them, but they wanted opportunities for advancement, and Ferris Institute offered opportunities. They came here, took college prep courses, and then went on to schools like University of Michigan or Northwestern.

Hampton did have college prep and vocational instruction, but the vocational-technical education that people were getting at Ferris was not the same vocational-technical that people were getting at Hampton. At the time, [Hampton’s] programs were, like, brick laying and meat science because that was acceptable work for African Americans in the Jim Crow South—whereas, up here, you had a more academic curriculum. Even though on paper [Hampton and Ferris institutes] were both committed to technical education, in the real world, those educations produced different employees.

So, they came here because they were welcome—that doesn’t mean they didn’t experience some prejudice in the city. They sometimes faced, as former Ferris President Gerrit Masselink said, “bitter prejudice,” whether they were here or at Michigan Agricultural College. But they had an advocate here, and Mr. Ferris didn’t just advocate for them while they were here; he also helped some of them get into graduate school and made loans to some of the students. He took great interest in them.

At that time in the United States, the common economic experience was poverty. People lived hard, and they understood hardship. They understood what it was like to be hungry and what it was like to struggle. If you look at the life of Mr. Ferris, it’s not completely accurate to say that he came from humble beginnings. His family was poor, and they struggled, but he achieved great things and created an institution where other people were given opportunities to be successful.

If we could magically transport to the past and look at the safe in Woodbridge and Helen’s home, we would find promissory notes from students to the Ferrises. He understood that they didn’t have money, and he had an opportunity to help them despite their poverty. It’s not some silly slogan, “To make the world better.” He lived like that.

Keep in mind, institutions in those days, the early 1900s, were often aligned with the personality and value system of their founder. This was his institution, and so it reflected a great deal of who he was, what he believed, and how he lived his life.

FH: When you look at the first Ferris class, it’s well documented that there were five women and 10 men. So, Mr. Ferris provided opportunity for women, as well, early on, when most places in the country wouldn’t do that. His wife and other women taught here. And we found that, in the late 1890s, international students were coming here. Ferris had English as a Second Language courses for these students, and, again, I don’t think that you would have found that in most places around the country. As David said, “Mr. Ferris had something. There was something different about him.”

I want to give credit here to Fran Rosen, one of the librarians at Ferris’ Library for Information Technology and Education. We asked her to do some research using newspaper microfilm, and she found one of the biggest breakthroughs of this story, which is that, in 1902, [Tuskegee Institute founder] Booker T. Washington came here to Ferris to speak. He was brought here by the Ferrises and by the Ferris Cooperative Association—which was the alumni, students, faculty and staff. They brought him here, and the community welcomed him and embraced him, and it was a sold-out crowd. They wrote about it in the newspaper.

The article from the [Big Rapids] Pioneer states that Booker T. Washington spoke about how similar the work done at Ferris Institute was to the work that Tuskegee was trying to do, providing opportunities and general education for people who otherwise couldn’t have it. We know Ferris was attending conferences with Washington from 1913 to 1914, and Mr. Ferris spoke at a memorial service for Washington in Detroit in 1916. Washington was one of the most famous Hampton alums, so we’re thinking maybe that’s the connection.

AH: That touches on two of the most exciting aspects of this story, doesn’t it? That there’s still so much to be discovered, and a lot of it relates to figures who are significant not only to Ferris history but U.S. history.

FH: After I found that some of the students went to Hampton, I started Google-searching them. One the earliest African-American students I found was Percival Prattis [graduated 1917]. [My search] showed that he was the executive editor for the Pittsburgh Courier . This guy was one of the most prominent historical journalists in American history, and he went here, to Ferris, and we don’t know anything about him.”

Here we were, trying—in a sense, struggling—looking for people to highlight, yet we had these people here, and the story was starting to reveal itself. I kept looking, and we found guys like Belford Lawson [graduated 1920], who was the first African American to argue and win a case in front of the U.S. Supreme Court. I remember printing out that newspaper article, and I showed it to David, and he went to President Eisler, gave him the copy, and said, “This guy went here. These guys went here. This is a big story.” And then Dr. Eisler got excited and said, “Keep searching.”

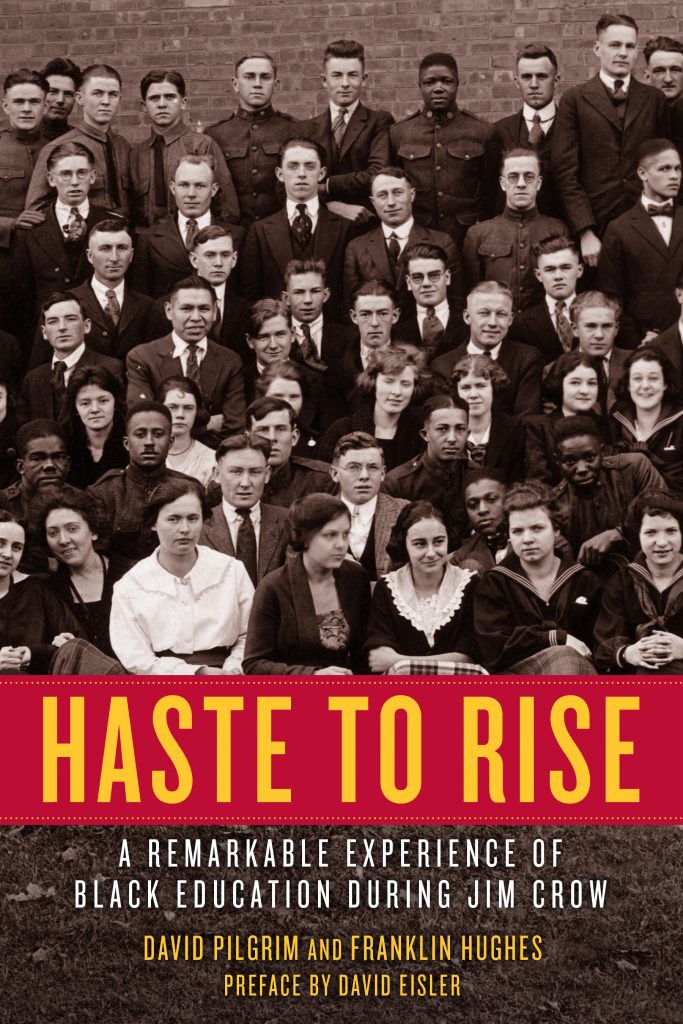

Detail from Ferris’ 1920 class photograph featuring African-American attendees.

Belford Lawson appears in the second row from the bottom, third from right.

DP: We recently found a 1920 class picture, and maybe a quarter of the people in it are women; there’s 20 to 25 identifiable African Americans, and they’re not segregated. We mentioned Belford Lawson, and [in the photograph] he’s just this young man, sitting. He looks so unassuming. That’s 1920, and 18 years later, he’s going to be a nationally known, history-making attorney.

I’m trying to figure out what to highlight about his life—you could write a book about several of these people, and that’s not an exaggeration. Prior to this research, I didn’t know what [Lawson’s] relationship was with John F. Kennedy. Lawson introduced Kennedy to prominent African Americans, both Republicans and Democrats, who otherwise had no interest in supporting him. He and his wife, Marjorie Lawson, were instrumental, certainly in the early days, in getting John F. Kennedy on his way to winning the presidency, if the black vote mattered, and it certainly did.

[Lawson] was the first African-American president of the YMCA, and he started a program with the National Basketball Association. He was much more than a guy who argued eight cases before the U.S. Supreme Court and won two important cases. He was a lifelong civil rights leader, a pioneer whose work helped this nation move beyond Jim Crow laws and practices.

Learn more about some prominent Hampton-Ferris attendees at

http://www.ferrismagazine.com/hampton-ferris-alumni/.

FH: The story just kept expanding. You find a guy and find out he was a prominent dentist, or he was the NAACP chapter president, or these guys were civil rights activists, and they were very prominent in the communities they had served.

Nate Harris [attended 1902-1903] was a Negro-league baseball star, a biracial, African American-identified man who not only played baseball; he played football. Harris played on a team called the Leland [later the Chicago Union] Giants. In 1902, the same year that Booker T. Washington spoke here, later that year, the team relocated to Big Rapids to become the Big Rapids Colored Giants. After that season, Harris stayed in Big Rapids, and he enrolled at Ferris Institute. This puts him here eight years before Gideon Smith, who was here from 1910 to 1912.

Harris enrolled at Ferris, played football for Ferris and coached the Ferris football team. We’re still doing research on it, but this makes him one of the earliest African Americans in the country to coach football at a predominantly white institution. If not the first, he definitely was one of the firsts.

The Ferris student body, the staff, the faculty embraced this kind of diversity. In one of the reports of the championship game in 1902, Harris kicked a 30-yard drop kick right before the half, which was phenomenal, and the whole student body ran onto the field and carried him off the field, cheering and celebrating. So, Nate Harris was a part of the community.

Nate Harris’ publicity photograph for the Chicago Union Giants, circa 1909. Photo: Chicago History Museum

When Booker T. Washington came here in 1902, it was nine months after he had eaten in the White House—it caused a big national controversy in the Jim Crow era, a black man eating in the White House. So, for Mr. Ferris to bring him here to be a keynote speaker was really taking a risk, but I think [the warm reception] also shows that this community was different than one might suspect.

AH: As a lifelong resident of Big Rapids, I wouldn’t picture this area having a lot of early diversity, and I would assume the attitudes of early white residents toward early African-American residents would mirror the attitudes of whites in other rural towns nationwide at the time.

FH: In reality, Michigan was a beacon of light to a lot of African Americans in the late 1800s. African Americans who lived in Ohio and northern border states thought Michigan was a great place because you could own property and a business, and you had other opportunities. If the people who are telling these stories aren’t investigating or don’t have this thought process that African Americans and people of color are a part of the historical fabric of this community, then they don’t think to ask or don’t think to search out these answers to find out the real story.

Who is left from those guys in the 1920s, in the 1910s, left here in Big Rapids to tell it? It’s “out of sight, out of mind” if there’s no representation of them left here. So, I think that kind of happened throughout the years in the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s—there really wasn’t anyone to say, “Hey, we were here. We were a part of this community.”

In Big Rapids, we have a new mural that just went up downtown, of the history of the logging industry in this area. It’s beautiful. It’s an amazing mural, fantastic, but it’s not all the way accurate. There were dozens and dozens of African-American families—my wife is from one of those families—who came here to Michigan to join the logging industry, yet they are not represented in the mural.

I think a lot of people in Michigan don’t even know our own history and how influential we were as a state. A lot of people ask us about why the Jim Crow Museum is located in Big Rapids, and, if you really look at the history of this area—with Mecosta, Lake County, Baldwin and Idlewild—there really is a large historical influence of African Americans in this community and in this area.

AH: So, this all started with the search for an image of Gideon Smith, whom you believed to be the first African-American student at Ferris, but then you found Nate Harris, who was here as early as 1902. Does that make him officially the earliest African-American student in Ferris’ history?

Hughes and Pilgrim now believe that Middleton E. Pickens (above) was Ferris’ first black attendee. He graduated in late 1901.

FH: We started doing some more research and found that, in 1900, there was an even earlier African-American student here, and his name was Middleton E. Pickens [graduated 1901]. There’s no connection between him and Hampton Institute, and we’re not really sure how he heard of Ferris, but we do know that in 1900 he was here. And what’s interesting about him is that he had college prep and general bachelor’s degrees from Pennsylvania’s Lincoln University. He had those degrees before he came here to Ferris, and he came to Ferris to get a pharmacy degree.

So, 1900 to the end of 1901, Pickens attended. As far as we know, he is the earliest African American to attend the Ferris Institute—16 years after its founding, which is pretty early on. We know that Mr. Ferris provided promissory notes and loaned money to him after he earned his pharmacy degree from Ferris, to attend the Detroit School of Medicine, from 1902 to 1906.

While Mr. Ferris was running for governor, his first attempt in 1904, Pickens started an independent group for voters of color in support of Ferris in Detroit. Apparently, he was rallying African-American voters to vote for Mr. Ferris, a Democrat. At that time, African Americans voting Democrat was unheard of, but here is Middleton Pickens, setting up these groups and organizations to help Mr. Ferris.

AH: Diversity and inclusion are such essential elements of the higher education experience now, and the legacy of diversity that you’re describing at Ferris is so relevant to them. Doesn’t it beg the question of how we lost track of this chapter in our campus history?

DP: There are people who have written about Woodbridge Ferris, and there are people who have written about Ferris Institute, and neither group told the stories we are researching. So, from the very beginning, even though we didn’t mean it to, [our research] has looked like a critique of other works because those other works did not include the stories about the Hampton-Ferris connection and Woodbridge Ferris’ commitment to racial justice and equality.

Franklin always says it’s easier to do this [research] today because of technology. We didn’t have technology like newspapers.com 30 years ago. If you’ve sat in a room with microfilm, you know it’s boring, time-consuming, head-hurting work. Now we have technology that does what microfilm did, except as fast as Google. So, the technology is different and better. You have to know to look for it in the first place, and then you have to look for it. We have history groups and resources here, and I think they have done work that is useful in telling Ferris’ story, but what you need is someone who is going to dig in and do the detective work on the hidden stories.

I think there’s a misconception that, if you have to look for it, then it wasn’t significant. We assume we already know the big stuff. That’s not accurate. This is not a footnote. It’s a chapter.

FH: In 1915, Woodbridge Ferris gave a speech at the Lincoln Jubilee, and it’s recorded in the Michigan Manual of Freedmen’s Progress. One of the things that Mr. Ferris talks about is how he held his college accountable to his values.

There had been an incident with an African- American woman who attended Ferris—we don’t know who she was, but we know she was biracial, so it wasn’t necessarily evident right away that she was of African descent. When the women in the housing unit found out, they wanted her removed from the house. [Reflecting on it in his speech at the jubilee], he said, “On the following morning, I said to the school that I supposed I was living in Michigan, but I concluded, after describing this situation, that I was living in Louisiana. The Ferris Institute is one of the most democratic schools in the United States. It has no color line; it has no age limit; it has no prior requirements for admission. It is open to every man and woman, every boy or girl who is hungry for an education.”

AH: So, that quote—minus the first sentence—has been used extensively to convey generally that diversity was a founding concept at Ferris, but removing that first sentence also obscures the more compelling story in the details of that situation?

FH: So, we know these quotes, but do we know the context of them? Mr. Ferris said, “We are this democratic school, this opportunity school,” but he’s saying this based on the situation that there was this prejudice going on, and he was addressing it, straightforward.

DP: He also found her a place to stay. You’re dealing with a different period in America’s race relations—a time when racial discrimination was normative. Ferris saw an injustice and he addressed it, talked to everybody involved, challenged the racial ideas of the individuals who were involved, challenged them to be fair. He challenged the whole institute, and, I repeat: He found her a place to live.

I’m sure he did not want to say negative things about his school, his life’s work, but here he was, speaking openly and honestly, in public. He would have gotten no joy out of doing that, but he needed to say that racial discrimination is wrong and it’s wrong to mistreat people. The last part of that quote I’ve seen over the years, around campus and in different books with quotes of his, but it’s different when someone asks themselves questions like “Why did he say that?” “What was going on?” “What does that say about him?” “What does that say about the university?”

Maybe the person who brought that quote forth, maybe they wanted the berry without the thorns because, if you just take the last part he says, it sounds like some sweet, beautiful comment, but it’s not accurate without the context. The better story of it is the other part.

AH: What do you want people to take away from the book that you’re writing about this?

DP: Part of what we’re doing is trying to make real the platitudes that people have reduced Mr. Ferris’ words to. So, if you ask people, they just give you the quote that Ferris was the most democratic or whatever, but they don’t ask the questions, “Is he telling the truth? Was he actually living it?” And our research revealed a commitment to fairness and social justice was reflected in his actions. There are so many examples. That’s a part of the story, too. Woodbridge cared about people, irrespective of their racial or ethnic backgrounds.

AH: Which sometimes, almost certainly, would have required a fair amount of risk on his part.

FH: You know, Ferris says later in that [Lincoln Jubilee] speech, “It seems, however, that we shall not be able to secure African Americans the educational rights, the social rights, the political rights they are entitled to without first eliminating, in a large measure, race hatred.” And this is 1915.

DP: Yeah, the year of [release of the film] “The Birth of a Nation,” which was sweeping the country, and he’s one of the few governors who condemned it.

FH: Yeah, publicly said, “It is damnable.”

DP: We have the benefit that, when we look at Ferris Institute’s history honestly, we find these great things. So, yes, it is a story about Hampton, but [Mr. Ferris] supported students of color whom he did not have to, so it’s also a story about the character of our founder. And he didn’t do it just for African Americans—he did it for Canadians and for other folks. He impacted many lives. We haven’t mentioned that he also was arguing for women’s rights. That was so far ahead of his time, and not just in terms of education, but in terms of addressing abuse and addressing how women were treated in the home, in the workplace and everywhere else. Maybe he never used the words “social justice,” but he lived a life of social justice. We also want to see those stories told.

One of my messages to our campus now is that we did not create Ferris; we inherited it. So, you need to understand what your inheritance was. When you don’t talk about Woodbridge Ferris’ work in terms of extending opportunity to women, to international students, to African Americans, to students with disabilities—to all—you’re really not telling a fair story of our founder. When you tell the story of the Hampton-Ferris connection, then you tell a more accurate story of Ferris’ history, about the institution and the founder.

People who are interested in creating an inclusive environment can look back at the institution’s past and draw some inspiration from it. Woodbridge Ferris created an institution for all people. That was his legacy. It is our mandate.

FH: It’s important for people to know that the fabric of the institution is probably not what you think it is—it’s better, it’s greater. This is an amazing story. It shows that this was an inclusive place, an opportunity place. It’s always been that.

Pilgrim and Hughes are seeking help from readers to develop this story. If you have information related to diverse Ferris Institute attendees from 1900 to 1930, or if you are interested in providing research assistance, please email [email protected].

One week before this interview, HBO’s Vice News aired a segment on Pilgrim and the Jim Crow Museum. View that segment at https://video.vice.com/en_us/video/a-basement-at-ferris-state-university-is-filled-with-dollar13-million-dollars-of-racist-objects/5aac566df1cdb3360c184132.