Silvia Federici expands on her analysis in Caliban and the Witch, exploring how the body is central to the reproduction of capitalism but also to anti-capitalist resistance.

This is an excerpt from Silvia Federici’s Beyond the Periphery of the Skin: Rethinking, Remaking, and Reclaiming the Body in Contemporary Capitalism (PM Press, 2020), republished with permission from the publisher.

The history of the body is the history of human beings, for there is no cultural practice that is not first applied to the body. Even if we limit ourselves to speak of the history of the body in capitalism, we face an overwhelming task, so extensive have been the techniques used to discipline the body, constantly changing, depending on the shifts in the different labour regimes to which our body was subjected.

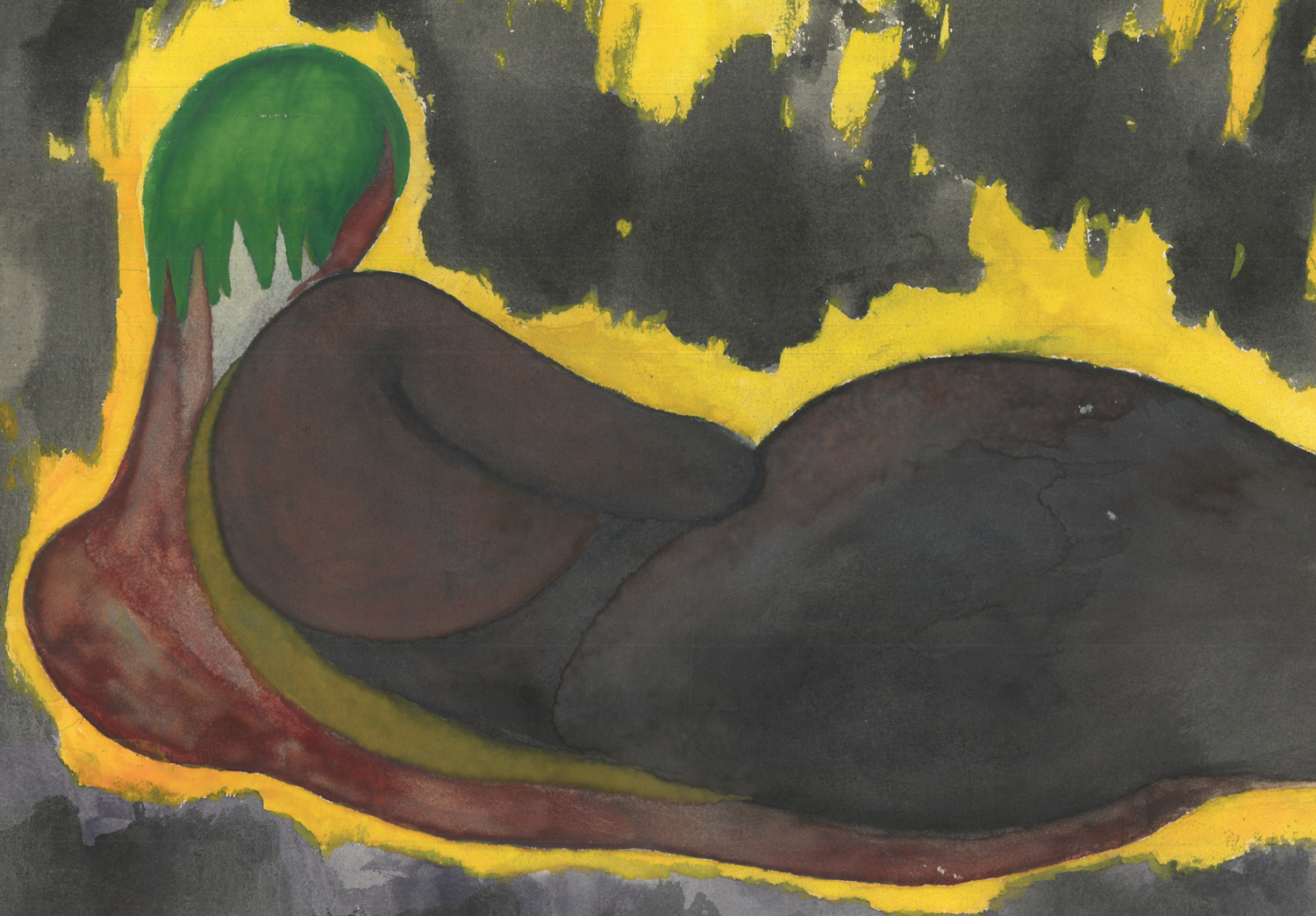

A history of the body can be reconstructed by describing the different forms of repression that capitalism has activated against it. But I have decided to write instead of the body as a ground of resistance, that is, the body and its powers – the power to act, to transform itself and the body as a limit on exploitation. There is something we have lost in our insistence on the body as something socially constructed and performative.

The view of the body as a social (discursive) production has hidden the fact that our body is a receptacle of powers, capacities and resistances that have been developed in a long process of coevolution with our natural environment as well as intergenerational practices that have made it a natural limit to exploitation.

By the body as a “natural limit” I refer to the structure of needs and desires created in us not only by our conscious decisions or collective practices but also by millions of years of material evolution: the need for the sun, for the blue sky and the green of trees, for the smell of the woods and the oceans, the need for touching, smelling, sleeping, making love.

This accumulated structure of needs and desires, that for thousands of years has been the condition of our social reproduction, has put limits on our exploitation and is something that capitalism has incessantly struggled to overcome.

Capitalism was not the first system based on the exploitation of human labour. But more than any other system in history, it has tried to create an economic world where labour is the most essential principle of accumulation. As such it was the first to make the regimentation and mechanisation of the body a key premise of the accumulation of wealth. Indeed, one of capitalism’s main social tasks from its beginning to the present has been the transformation of our energies and corporeal powers into labour powers.

Related article:

In Caliban and the Witch (2004), I have looked at the strategies that capitalism has employed to accomplish this task and remold human nature, in the same way as it has tried to remold the earth in order to make the land more productive and to turn animals into living factories. I have spoken of the historic battle it has waged against the body, against our materiality and the many institutions it has created for this purpose: the law, the whip, the regulation of sexuality, as well as myriad social practices that have redefined our relation to space, to nature and to each other.

Capitalism was born from the separation of people from the land, and its first task was to make work independent of the seasons and to lengthen the workday beyond the limits of our endurance. Generally, we stress the economic aspect of this process, the economic dependence that capitalism has created on monetary relations and its role in the formation of a wage proletariat. What we have not always seen is what the separation from the land and nature has meant for our body, which has been pauperised and stripped of the powers that precapitalist populations attributed to it.

Nature, as Marx (1988, 75-76) recognised it, is our “inorganic body”, and there was a time when we could read the winds, the clouds and the changes in the currents of rivers and seas. In precapitalist societies people thought they had the power to fly, to have out-of-body experiences, to communicate, to speak with animals, take on their powers and even shape-shift. They also thought that they could be in more places than one and, for example, come back from the grave to take revenge of their enemies.

Not all these powers were imaginary. Daily contact with nature was the source of a great amount of knowledge reflected in the food revolution that took place especially in the Americas prior to colonisation or in the revolution in sailing techniques. We know now, for instance, that the Polynesian populations used to travel the high seas at night with only their bodies as their compass, as they could tell from the vibrations of the waves the different ways by which they could direct their boats to the shore.

Fixation in space and time has been one of the most elementary and persistent techniques capitalism has used to take hold of the body. See the attacks throughout history on vagabonds, migrants and hobos. Mobility is a threat when not pursued for the sake of work, as it circulates knowledge, experiences, struggles. In the past the instruments of restraint were whips, chains, the stocks, mutilation, enslavement. Today, in addition to the whip and the detention centres, we have computer surveillance and the periodic threat of epidemics such as avian flu as a means of controlling nomadism.

Mechanisation – the turning of the body, male and female, into a machine – has been one of capitalism’s most relentless pursuits. Animals too are turned into machines, so that sows can double their litter, chicken can produce uninterrupted flows of eggs, while unproductive ones are ground up and calves can never stand on their feet before being brought to the slaughterhouse. I cannot here evoke all the ways in which the mechanisation of body has occurred. Enough to say that the techniques of capture and domination have changed depending on the dominant labour regime and the machines that have been the model for the body.

Related article:

Thus, we find that in the 16th and 17th centuries (the time of manufacture) the body was imagined and disciplined according to the model of simple machines, like the pump and the lever. This was the regime that culminated in Taylorism, time-motion study, where every motion was calculated and all energies were channeled to the task. Resistance here was imagined in the form of inertia, with the body pictured as a dumb animal, a monster resistant to command.

With the 19th century we have, instead, a conception of the body and disciplinary techniques modelled on the steam engine, its productivity calculated in terms of input and output, and efficiency becoming the key word. Under this regime, the disciplining of the body was accomplished through dietary restrictions and the calculation of the calories that a working body would need. The climax, in this context, was the Nazi table that specified what calories each type of worker needed. The enemy here was the dispersion of energy, entropy, waste, disorder. In the US, the history of this new political economy began in the 1880s, with the attack on the saloon and the remolding of family life with at its centre the full-time housewife, conceived as an anti-entropic device, always on call, ready to restore the meal consumed, the bodies sullied after the bath, the dress repaired and torn again.

In our time, models for the body are the computer and the genetic code, crafting a dematerialised, disaggregated body, imagined as a conglomerate of cells and genes, each with their own programme, unconcerned with the rest and the good of the body as a whole. Such is the theory of the “selfish gene” – the idea that the body is made of individualistic cells and genes all pursuing their programme, a perfect metaphor of the neoliberal conception of life, where market dominance turns against not only group solidarity but solidarity within ourselves. Consistently, the body disintegrates into an assemblage of selfish genes, each striving to achieve its selfish goals, indifferent to the interest of the rest.

To the extent that we internalise this view, we internalise the most profound experience of self-alienation, as we confront not only a great beast that does not obey our orders but also a host of micro-enemies that are planted right into our own body, ready to attack us at any moment. Industries have been built on the fears that this conception of the body generates, putting us at the mercy of forces that we do not control.

Inevitably, if we internalise this view, we do not taste good to ourselves. In fact, our body scares us, and we do not listen to it. We do not hear what it wants but join the assault on it with all the weapons that medicine can offer: radiation, colonoscopy, mammography, all arms in a long battle against the body, with us joining in the assault rather than taking our body out of the line of fire. In this way, we are prepared to accept a world that transforms body parts into commodities for a market and view our body as a repository of diseases: the body as plague, the body as source of epidemics, the body without reason.

Our struggle then must begin with the reappropriation of our body, the revaluation and rediscovery of its capacity for resistance, and expansion and celebration of its powers, individual and collective.

Dance is central to this reappropriation. In essence, the act of dancing is an exploration and invention of what a body can do: of its capacities, its languages, its articulations of the strivings of our being. I have come to believe that there is a philosophy in dancing, for dance mimics the processes by which we relate to the world, connect with other bodies, transform ourselves and the space around us. From dance we learn that matter is not stupid, it is not blind, it is not mechanical but has its rhythms, its language, and it is self-activated and self-organising. Our bodies have reasons that we need to learn, rediscover, reinvent. We need to listen to their language as the path to our health and healing, as we need to listen to the language and rhythms of the natural world as the path to the health and healing of the Earth. Since the power to be affected and to effect, to be moved and to move, a capacity that is indestructible, exhausted only with death, is constitutive of the body, there is an immanent politics residing in it: the capacity to transform itself, others, and change the world.