By Fiorella Lecoutteux

Peace News

May 7th, 2018

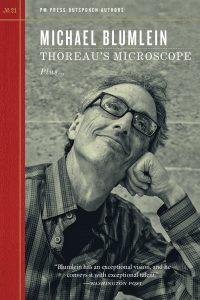

The physician and award-winning writer Michael Blumlein, started his career as a medical researcher in San Francisco. Published in 1988, his first science fiction novel, The Movement of Mountains, set the tone for his subsequent work: short stories, essays and novels merging science fiction, fantasy and horror and featuring his own signature perspective on the human species. His stories are imbued with a deep sense of social justice and individual freedom – as well as a good dose of humour.

This collection gives us a selection of his short stories, a new essay (‘Thoreau’s Microscope’) and a revealing interview with editor Terry Bisson.

‘Paul and Me’, published in 1997, is the story of an unlikely meeting between the narrator and a fantastical giant, and the lasting consequences of their meeting for both of them. Dedicated to Blumlein’s friend and fellow SF writer Terry Parkson, who died of AIDS, it tackles the mental and physical toll exacted by the disease.

In ‘Y(ou)r Qu(an)tifi(e)d S(el)f’, published in 2014, the narrator addresses the reader through the lens of muscle weight, percentages, kilos and personality tests. By reducing the reader’s body to its biological apparatus, Blumlein creates a comically detached and premonitory take on our increasing disconnection to ourselves and to the world.

I particularly enjoyed reading ‘Know How, Can Do’ (2001), the title referring to the human tendency to try an experiment simply because we can. In it, the scientist Sheila Downey has created a new Frankenstein’s creature – 61.8% worm and 38.2% human – which develops ‘human’ characteristics as the story unravels. Through their exchanges, Michael Blumlein brilliantly questions the ethics of human experiments. In the interview Blunstein celebrates the ways in which PETA and other activist groups have successfully pressured medical schools to cease using animals for scientific practice: a victory for ‘animal rights activists’ but also for those who believe that ‘all life is precious.’

Blumlein’s writing is effective and empathetic, and one is reminded how personal and political science fiction can be owing to its great force of invention and its ability to ‘stretch the mind.’ By merging hard science and social justice with fiction, he flips classical narrative tropes on their head allowing the reader to see the world from entirely new perspectives. His stories make space for thinking about our world and should help inspire those who are trying to change it for the better.