By Ron Jacobs

Counterpunch

February 7th, 2020

Up until the early part of this century, most drugstores in the United States had full-on newsstands that sold daily newspapers, the Racing Form, and weekly magazines. They also had MAD magazine, comic books, pop music fan mags, crossword puzzles books, and hundreds of paperback titles. Running the gamut from pulp detective fiction to romance and best-selling works, these were usually cheaply priced.

In the late 1960s, I spent many hours at the various drugstore newsstands in my suburban town reading for free. It was at one such establishment where I discovered Mickey Spillane, Harlan Ellison, Frederick Pohl, Herman Hesse, and the Harvard Lampoon, among others. I would finish up my morning newspaper route on Saturdays and head to the drugstore in the local shopping center. There I would meet up with other newspaper carriers and eat breakfast. That was where I had my first cup of coffee. After the three or four of us delivery boys finished breakfast, I would head to the newsstand to catch up on the newspapers I didn’t deliver and the magazines I didn’t want to buy and my parents didn’t subscribe to. After a quick survey of this media, I would scan the paperbacks and find one to read. If, after a half hour or so of reading, I was intrigued I would buy the book. Usually, the cashier didn’t care what I was buying. Sometimes, however, the cashier would be some uptight older woman or a wannabe’ preacher and they would refuse to sell me the paperback. This usually meant that I would go back to the newsstand and ultimately walk out with the book without paying for it. My library of paperback fiction resided in a box under my bed in the room I shared with one of my brothers. It was mostly made up of pulp novels featuring seedy criminals, badass private eyes, sexy covers, science fiction speculations, and fiction/new journalism popular with hippies and freaks—Herman Hesse, Ken Kesey and Tom Wolfe come immediately to mind.

When I moved with my family to a military installation in Frankfurt am Main, Germany in 1970 I found a similar trove of treasure at the bookstore run by the Post Exchange and in an English language bookstore near central Frankfurt. The latter store featured British editions published mostly by Penguin and included many books and authors not available in US editions. Despite these recollections, this review is not a lament for the almost lost institution of drugstore newsstands. Instead, it is about the pulp fiction that populated the newsstand shelves.

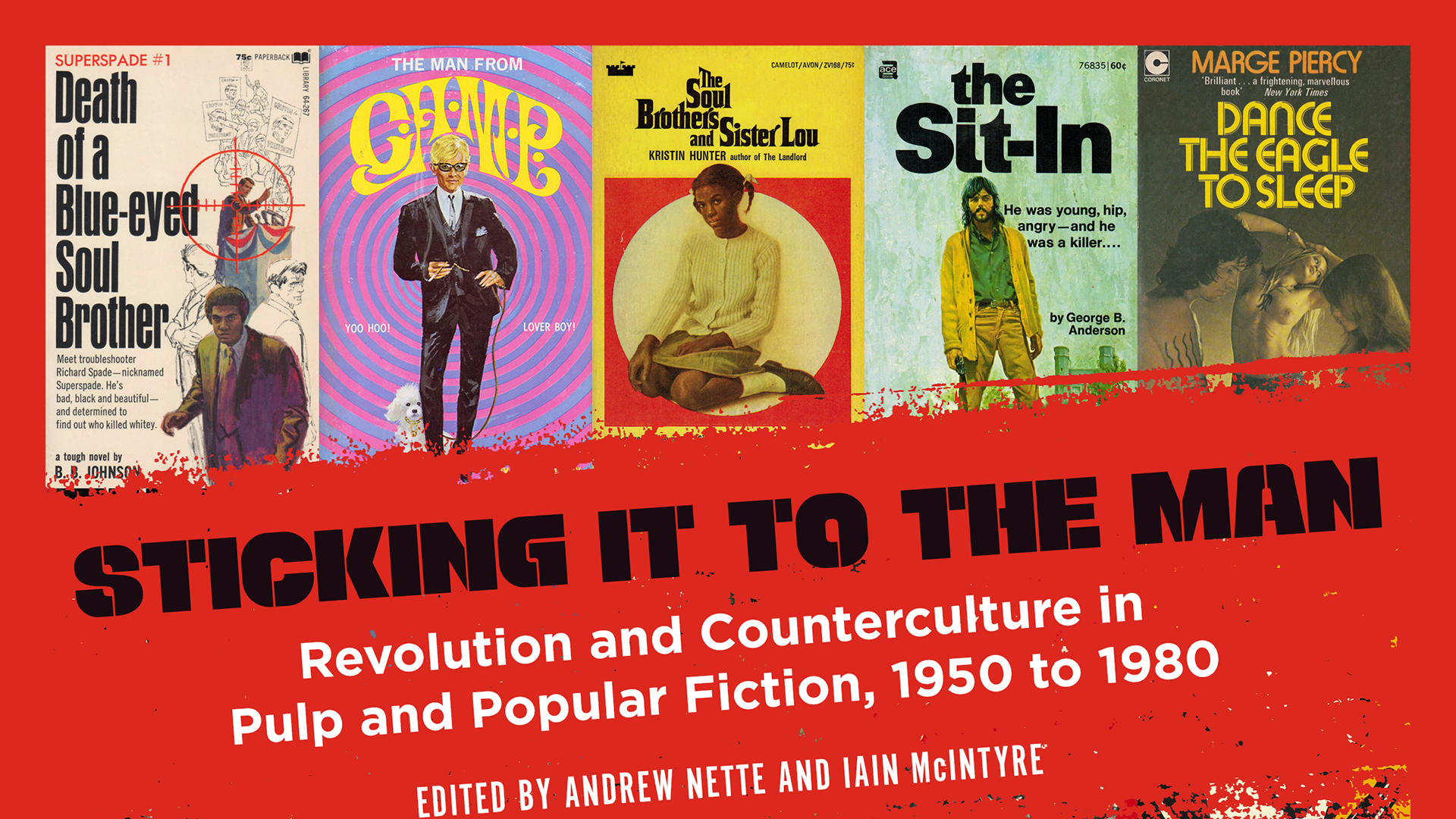

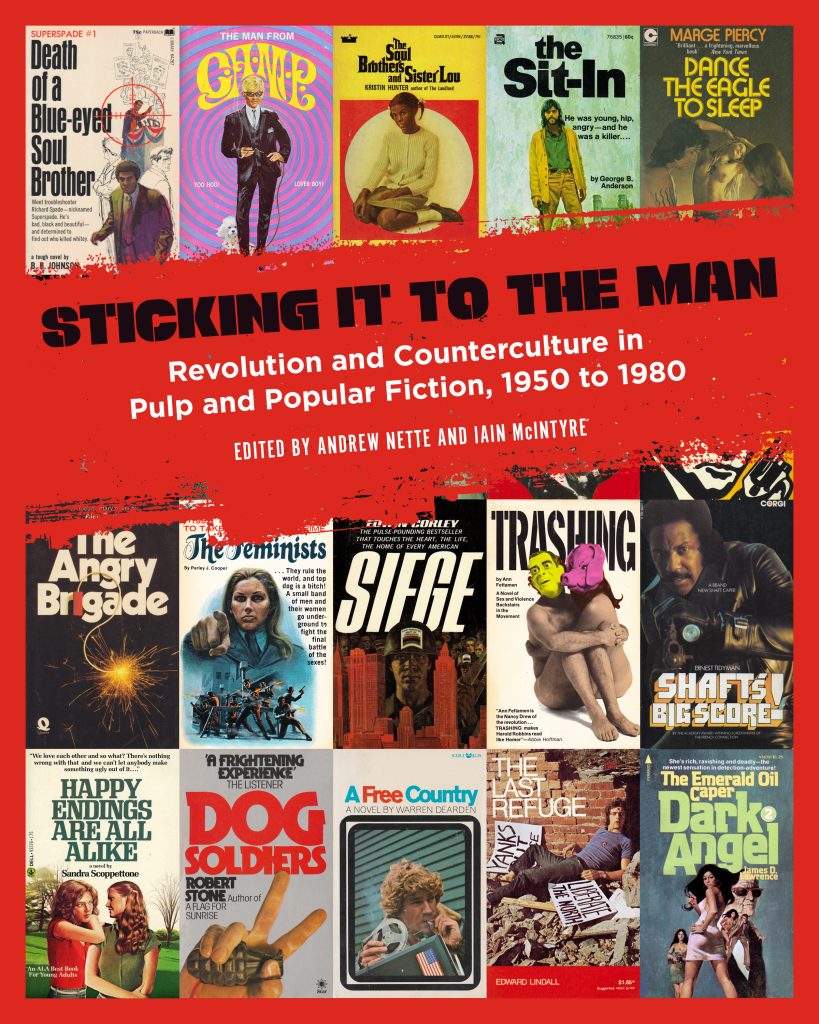

In 2019, PM Press published the second in its series of pulp fiction reviews. Titled Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980, this text is a collection of essays discussing and reflecting on this particular type of literature. Sprinkled throughout with full color photographs of book covers, the essays are a lively and varied look at the presence of the counterculture and new left in popular fiction. Given the overall reactionary politics of most detective fiction at the time, the appearances of freaks and left radicals in the books are predominantly sensationalist and unfavorable. However, there are exceptions. Indeed, some of this fiction was written from a left perspective, some from a feminist perspective and some had a Black nationalist take.

The book opens with a short essay discussing the nature of pulp and popular fiction in the long Sixties and the appearance of the aforementioned movements in that fiction. Appropriately enough, the next essay is about a writer who provided a bridge from the pre-Sixties period through the Sixties: Chester Himes. Himes was a crime fiction writer who made the African-American street come alive in his novels featuring two Harlem cops with an ear to the street and a serious sense of justice. Other similar writers discussed in the text drew some of their inspiration from Himes (and Iceberg Slim, who has an essay devoted to his works in the text). These include Joseph Perkins Greene, Joe Nazel and Ernest Tidyman, the author of the Shaft novels. The essays discussing these writers and their works place the novels in the context of the time period and its liberatory ethos while simultaneously reflecting on their place in the African-American canon.

Another focus of this collection is the youth culture of the period. As the book makes clear, much of this fiction was sensationalized and focused on drug use and sex. However, certain writers went beyond the obvious and composed novels that treated the counterculture as more than a drug-fueled orgy and the new left as more than a bunch of spoiled rich kids afraid to go to war. Taking it to the Streets contains essays discussing works from both perspectives. These include Fugs/Yippie member Ed Sanders’ novel Shards of God and several of Marge Piercy’s works, most of which can also be considered feminist fiction. Like its treatment of the counterculture, this book’s approach to feminist fiction looks at works written by feminist authors and their opposite. As for fiction from and for the gay and lesbian reader, the discussion centers mostly on the erotica which was prevalent on the market at the time.

This book is a meditation on a subject rarely considered in retrospect, given the transient nature of this type of literature. The writers enlisted to discuss the authors and their works do a fine job of highlighting the novels, their authors, characters and setting, while extracting the fiction’s meaning in the context of the Sixties as history. The multiple full-colored photos of many of the book covers not only enhances the considerations of the works, but provide the reader with a glimpse into the world of pulp fiction at one of its peaks in popular culture. Indeed, the covers made me wish I was back in one of those drugstore newsstands surrounded by hundreds of paperbacks available for less than two dollars.