By Richie Narvaez

Mystery Tribune

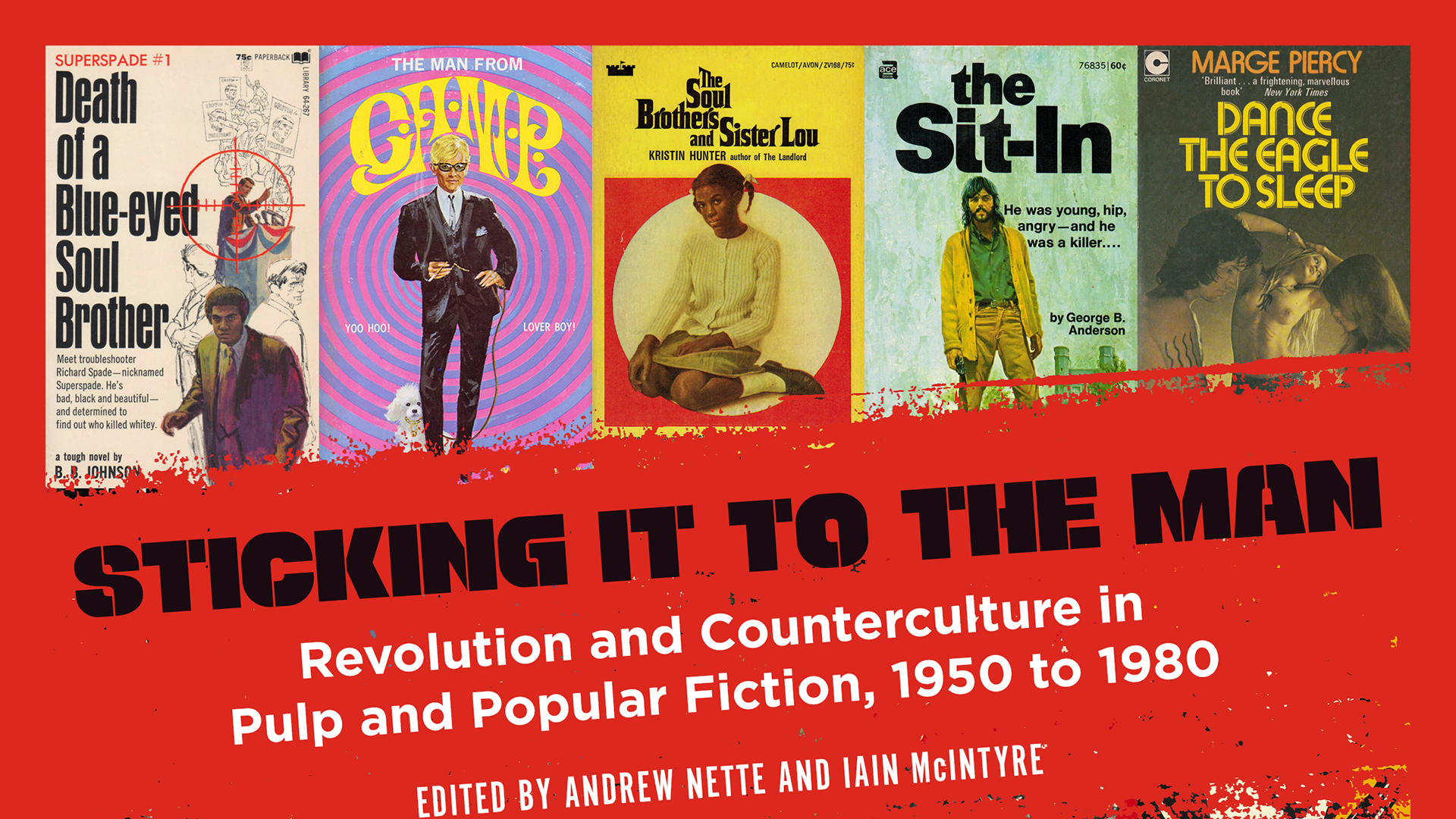

The trashiest pulp fiction may seem like nothing more than lurid lit, but it can reveal reams of insight into what its writers, readers, publishers, and the world was thinking — and fearing — at the time it was published. That’s one of the takeaways of the endlessly entertaining new anthology Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980, edited by Iain McIntyre and Andrew Nette.

Filled with page after page of gaudy, vivid paperback covers (they had to titillate, since the covers were the only marketing the pulp publishers could afford), illustrated biographies, extensive book summaries, and author interviews, Sticking It to the Man covers how the changing politics and culture of the Long Sixties (the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, approximately) was reflected in pulp and popular fiction in the U.S., the UK, and Australia.

So we get crime thrillers, adventure books, and erotica exploring and exploiting such subjects as civil rights, Black Power, feminism, the New Left, and gay and lesbian sexuality.

In a fantastic essay, crime author Scott Adlerberg examines Chester Himes’s brutal Coffin Ed Johnson and Grave Digger Jones series, which turned increasingly plotless and violent. In another essay, one of the highlights of the book, crime author Gary Phillips discusses the archetypes of black male characters in crime fiction.

…[this book] covers how the changing politics and culture of the Long Sixties (the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, approximately) was reflected in pulp and popular fiction in the U.S., the UK, and Australia.

Editor Nette, author of two excellent crime novels himself, delves deeply into Wally Ferris’s Across 110th Street, which became an important Blaxploitation film. See also the Shaft book series (six books and written by a white author Ernest Tidyman—who knew?), covered here from different angles by both Michael Gonzales and Steve Aldous.

Signaling the increased relaxation of mores and censors, these pulps gaudily gave voice to previously marginalized groups and subcultures, sometimes bizarrely, often stereotypically. In many cases, for example, with young gays or lesbians, it let them know that were not alone in the world.

Of course, at the same time, some books were a backlash against these revolutionary ideas. In Bill Osgerby’s essay on Pulp Feminism, for example, he discusses Parley J. Cooper’s The Feminists, a sci-fi tale in which women have taken over the U.S., a story that is “so frighteningly possible,” reads the cover line. After the “final battle of the sexes,” the story concludes: “Unless we return rights to makes and make them equals, our country will be torn apart.”

Sticking It to the Man is massive undertaking by the editors and authors. It’s the kind of book you can dive into again and again and discover new things or learn new things about the familiar: the issue of adolescent homosexuality, fictional vigilantes, Looking for Mr. Goodbar, the heyday of the lesbian pulp novel, the true story behind E. R. Braithwaite’s To Sir, with Love, the portrayal of Aborigines in pulp, Marge Piercy’s Yippie Literary days.

What seems like heaps of trivia builds into revelations about the Long Sixties’ audience, who seemed appalled but enthralled. You begin to see how the throwaway stuff of our lives, that ephemeral content says so much about who a people are. Then of course you have to wonder: What will future generations make of our current trash, our posts, popcorn cinema, reality shows, and porn clicks? And there’s no tossing our stuff in the bin.

This volume is the second in a series that began with the equally fascinating Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950 to 1980 (PM Press, 2017), also edited by McIntyre and Nette.

That anthology covered the depiction of postwar youth culture in mass-market pulp, with an emphasis on juvenile delinquent novels and subcultures from Beats to bikers and skinheads to Satanists. A third, tentatively titled Dangerous Visions & New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction, 1950 to 1980, is due out next year.

As you might imagine, these are not the kind of books to read if you want to reduce your TBR pile. On every page is a book cover or essay that will send you rushing to wherever you get your book fix. (I immediately sought out Lee McGraw’s 1976 novel Hatchett, the solo adventure of a female PI, and Marc Olden’s Black Samurai series after reading about them here.)

At the same time, there are many books noted here you might be glad you never have to read but will love having read about. But if you’re a lover of pulp and a lover of history, do yourself a favor and drop out and dig into Sticking It to the Man.