By Meredith Goldsmith, Anna Kryczka, Catherine Liu

Los Angeles Review of Books

Jenny Brown Responds to Meredith Goldsmith, Anna Kryczka, and Catherine Liu’s “Anti-Labor Politics” (September 9, 2019):

DEAR EDITOR,

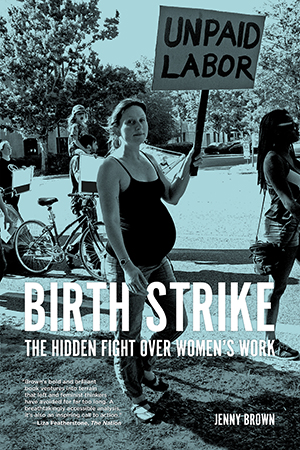

In “Anti-Labor Politics,” (September 9) the reviewers misread my book, Birth Strike: The Hidden Fight Over Women’s Work. I’m not calling for a birth strike, I’m saying women in the United States are spontaneously conducting one, and since our individual decisions are pressuring the power structure, we should now make collective demands. From this misunderstanding they suspect that I’m suggesting individual solutions when in fact I say that “there is no personal key to liberation, only collective struggle and society-wide solutions.”

The reviewers argue that it is reactionary to ask parents to accommodate themselves to the economic hellscape of neoliberalism. I agree! I even charge those who argue this — by recommending birth control to low-wage workers — with being modern-day Malthusians. Far from “naturaliz[ing] the scarcity mindset of neoliberalism,” I take on that mindset, arguing for workplace rights, defending Social Security, and showing how neoliberal policies push the costs of parenthood onto the family, from childbirth to college.

The reviewers say, “We hoped that Brown would conclude her book with a call to all workers, including caregivers, to organize for a family wage. Such a family wage might be a combination of paid parental leave, subsidized child care and elder care, universal health care…”

In fact, the last chapter is devoted to how we should organize for exactly these things, and the tricks and traps that we should avoid (means-testing, market-based solutions). I included hard-to-miss bullet points:

- National health care for everyone, health care that is not dependent on a job or a husband

- Universal free quality child care and elder care

- Paid parental leave for both parents

- Shorter working hours (with no reduction in pay)

I argue that child-care subsidies, which are generally means tested, should be scrapped in favor programs that cover everyone. Universal programs unite the many to defeat the few and increase the power of the working class vis-à-vis employers.

It’s odd to hear feminists calling for a family wage because this model puts women in a position of dependency on male “breadwinners.” The family wage is also the excuse for paying women less, so historically it is in contradiction with equal pay. I suggest that rather than going back to the family wage, we should go forward to a social wage, a term which describes gains that European workers and women have actually won, that are provided universally, and not dependent on employers.

The point of consciousness-raising is that most people are blaming themselves. Consciousness-raising allows us to direct our rage toward the source of the problem rather than ourselves or each other. But without organization — I call for dues-funded rather than foundation-funded organizations — we won’t get far. Consciousness-raising spread feminism widely in the 1960s, leading to some victories, but the radicals fell short on building lasting organizations, leaving room for liberals and neoliberals to hijack the movement.

Jenny Brown

National Women’s Liberation

¤

Meredith Goldsmith, Anna Kryczka, and Catherine Liu Respond to Jenny Brown:

Dear Jenny Brown,

We are grateful for your thoughtful response to our review. After reading your remarks we initially thought, how could all three of us misunderstand this book? We believe that we have substantive disagreements with many of your assumptions and conclusions. We want therefore to clarify our critique of your provocative and valuable work.

Clearly there has been a significant drop in fertility for white, professional women, which can be attributed to the high cost of raising a child — beyond pregnancy and birth — with the state shouldering as little of that burden as possible. In our age of austerity, quality child care and K–12 education are reframed as an opportunity for individual choice in a market rather than a sacred public good.

We believe that we cannot use “strike” to describe the decisions of a class of women who are in the privileged position of choosing not bear and raise children. You might argue that lower fertility rates reflect an “unconscious” strike, but we believe that this is a misuse of the term. A strike is a conscious, collective political action in which workers withhold their labor, often at great cost to themselves, to improve their collective situation. Withholding labor is leverage that allows workers to make demands to their bosses. We do not find, however, that capitalists, the wealthy and powerful who have outsize influence in the family planning policies in the United States and presumably our adversaries in this strike, are suffering as a result of our spontaneous actions. As you say, we are in a position to “make bold demands of those who benefit.” Who is benefiting? If we are currently striking, who is suffering from the loss? Or put another way, if we are currently striking, who is suffering from the loss of our labor?

Ultimately, we had no issues with — in fact we highly praise! — the introduction and last chapter of your book. We absolutely agree with and advocate for nationalized health care, universal child and adult care, and protected leave for both parents. Your point about means-testing is well taken. We found a disconnect, however, between the holistic approach to childbearing in these sections and the middle chapters, which privilege individual choices about childbearing over policy-making and collective action regarding labor and the labor of care.

Your work has inspired us to research the labor history of child care in the United States. Parents in the professional and upper classes who can afford to pay workers to care for their children are deeply attached to those people. These workers have always been underpaid for their valuable skills and are disproportionately women of color. Historically, they give up caring for their own children to care for the children of their employers.

As Allison Pugh has shown in her book, The Tumbleweed Society: Working and Caring in an Age of Insecurity, in what she calls “less advantaged” communities, “super-caretakers” emerge — women, but also sometimes men, who foster the children of family members or provide full-time care for disabled spouses. Pugh makes clear that their acts of altruism and self-sacrifice take place in a society where care is privatized and health care an expensive commodity.

We argue that the exploitation of working-class caretakers is largely the reason the United States has been able to get away with reproducing workers on the cheap for so long. A class analysis of caregiving in the United States, with attention to our particular racial history, is needed. We are particularly inspired by the collective action undertaken by the Los Angeles teachers union and parents of the children in the Los Angeles school district. The solidarity created by an intersection of interests, beyond reproductive rights, may provide the raised consciousness and rallying cause we really need to improve working conditions for caregivers, teachers and mothers and fathers alike.

Despite our disagreements, we celebrate and support your activism on behalf of Medicare for All. We know that you have written a hybrid book, one that provides research to frame activism. We are also encouraged by the fact that feminism as a movement has matured to the point where we no longer give each other purity tests and we can work toward common causes while accepting our mutual differences.

Respectfully,

Meredith Goldsmith, Anna Kryczka, and Catherine Liu

¤

Jenny Brown Responds to Meredith Goldsmith, Anna Kryczka, and Catherine Liu:

Dear Editor,

It’s not just white professional women who are having fewer children — working-class, Black, and Latina women are, too. The reasons are a lack of affordable child care, health care, paid leave, and decent wages and housing. This is not an elite issue, but goes to the very heart of working-class life. If we cannot afford families, what is our economy for?

I use the early 20th-century term “Birth Strike” to make the point that our individual responses to bad reproductive working conditions are having a political impact, whether we are aware of it or not. But, the reviewers ask, “Who is suffering from the loss of our labor?” I answer chapter by chapter: employers and the rich lose as economic growth suffers (Cheap Labor chapter). They can’t rely on ever larger cohorts to support retirees and may be called upon to put in money themselves (Social Security chapter). The military worries about recruitment (Cannon Fodder chapter). And the “American solution” to low birth rates, immigration, is giving employers headaches as immigrants demand their rights and organize against mistreatment (Immigration chapter).

The reviewers are correct that our system pushes the work of care onto families and low-waged caregivers, and even forces some of us to become “super-caretakers.” While the rich make bank, we stress out trying to take care of parents, children, and other family members, sacrificing our livelihoods, time, well-being, and health to do so. When we demand programs to help us in this work, they shrug and say there’s no money. But care work is the foundation of our economic structure, and as we increasingly refuse to do it, the necessity of our work becomes visible. Without it there is no economy. It’s time to demand our due.

Sincerely,

Jenny Brown

¤

Anna Kryczka teaches humanities full-time at Pasadena City College.

Catherine Liu is professor of Film and Media Studies at UC Irvine. Author of two academic monographs,Copying Machines: Taking Notes for the AutomatonandAmerican Idyll: Academic Anti-Elitism as Cultural Critique, she has also published a novel calledOriental Girls Desire Romance. She is working on a memoir, titledPanda Gifts.