By Jim Feast

The Fifth Estate

Summer 2019

Silvia Federici was born in Italy, taught for years in Nigeria, made many visits to South America, and now lives and teaches in the U.S. This broad experience, along with extensive scholarship, provides the wide angle lens which enables the perspective on view in her new book, Re-Enchanting the World.

She is able to assess both the octopoid worldwide reach of corporate capitalism and the resistance to its tentacles, manifested in a sustained effort to reinvigorate the commons.

Federici is an autonomist feminist Marxist and a longtime member of the Midnight Notes Collective. While orthodox Marxist theorists claim the economic mode of production determines all aspects of society, Federici argues Marx was not true to his claims because he limited economics to production (the creation of useable objects as exchange commodities), but ignored reproduction (the creation of socially useable human beings).

For Federici, the economic dimension of life involves two things. First, the nurturing and educating of human beings who are trained to fit into the economic system, a process labeled reproduction. This job is traditionally done by women. Second, the creation of objects necessary for life, done on farms, in factories and other places, called production, a job done by men and women, though traditionally men tend to claim this as their bailiwick. Marxists who identify production as the only significant component of economic life are missing half the picture.

In her 1998 magnum opus Caliban and the Witch, Federici examines the history of the creation of the bourgeois nuclear-patterned family, the social factory where the commodity called labor power is produced. This is the reproduction side of a capitalist system.

For Marx, the creation of conditions for a capitalist world were mainly brought about by appropriating the land from peasants and, in England’s case, often converting it to sheep grazing meadows. The dispossessed peasants were then forced into wage slavery as capital’s first proletariat.

Federici argues that a similar process went on with reproduction. The traditional extended household was replaced by the nuclear family which dictated a woman’s role that corresponded to what was needed for capitalism to function smoothly.

The peasant multi-generational family and women’s more varied roles in the peasant community as worker, doctor and (to a degree) shared decision maker, had to be eliminated. The witch trials which began in the first years of capitalist production, thus, were not bizarre episodes of religious fanaticism but, were ultimately about getting errant women (and in a few cases men) to fall in line and assume their places in capitalism, places much more confined and restricted than in the peasant community.

As Alex Knight describes this in a Fifth Estate review of the earlier book, “the ‘shock therapy’ of the Witch Hunt was used…to impose new discipline on the body, on female sexuality in particular, and to usher in a new social system based on…the devaluation of women’s labor” (see “Who Were the Witches?” FE #390, Fall, 2013). The process is described in a witch’s voice in Alice Walker’s The Temple of My Familiars, “When they burned me at the stake, I cursed them. I do not mind that they coveted my house…But what I refused to give up was my essence.”

In this new collection of essays, Federici underlines another weakness in Marxist theory. While Marx argued that the process of creating a domesticated labor force was only characteristic of the early stages of capitalism, Federici asserts that this is “something that has to be continuously reenacted, especially in time of capitalist crisis.”

An epicenter of the current version of this depredation appears in land grabs in Africa, in which foreign and domestic capitalists shift acreage used for subsistence farming into land for agribusiness cash crops, driving rural populations into the continent’s fetid cities. As Federici points out, “to this day at least 65 percent of the sub-Saharan population lives by subsistence farming, carried out mostly by women.”

The capitalist attempt to commercialize peasant production is largely a war on women. Federici observes: “Women are targeted because of their subsistence activities… which stand in the way of the World Bank’s attempt to create land markets.” Echoing what went on in Europe in the Middle Ages as depicted in Caliban, nowadays, she writes, “Witch-hunting…has returned with globalization, and in many regions of the world—Africa and India, in particular—is generally carried out by young, unemployed men, eager to acquire the land of the women they accuse of being witches.”

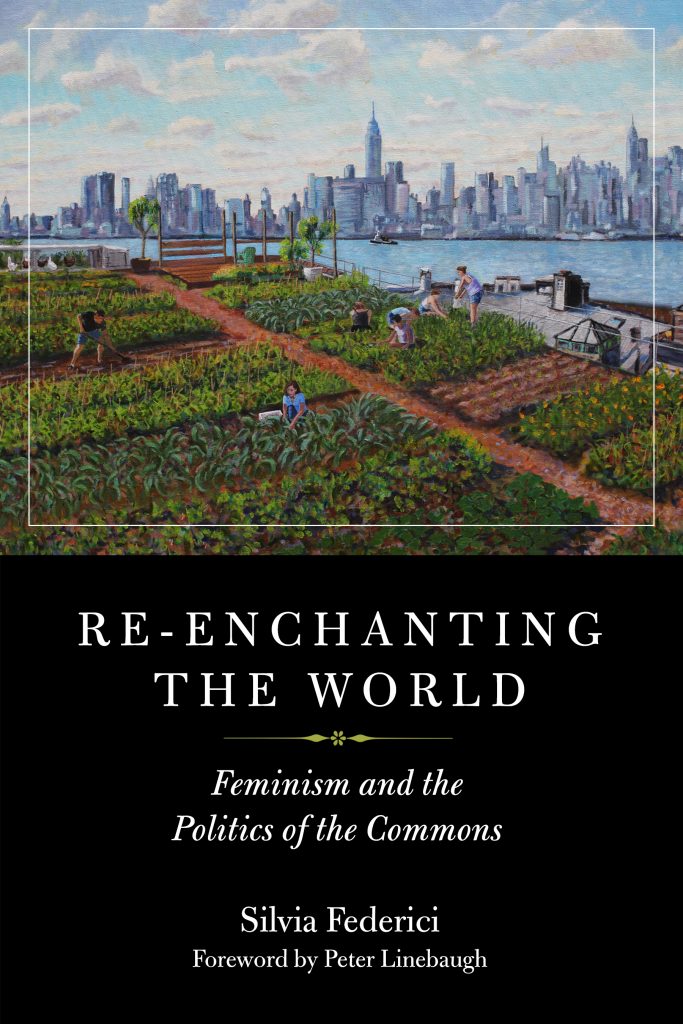

While one central focus of the African battle is the defense of communal lands by the rural women who farm them, another is pushing the city in the direction of a re-greening. “This is the ‘movement’ of landless women who have migrated to the towns and, using direct action tactics, appropriate and farm vacant plots of public land…along roadsides, rail lines, and in parks, without asking anyone’s permission or paying anyone a fee.”

Another front in this battle against privatization, one that Federici particularly documents in South America, is the transformation of domestic tasks into shared, community actions. One instance occurred in 1973 in Chile after the Pinochet coup: “Women in proletarian settlements, paralyzed by fear and subjected to a brutal austerity program, pooled their labor and resources. They began to shop and cook together in teams of twenty or more in the barrios.”

This meant the work of social reproduction ceased to be purely domestic and individual activity. Housework went into the streets alongside the big ollas (cooking pots) and acquired a political dimension. The significance of this was not lost on the police, who declared public cooking (and feeding) “subversive, communist activity.” Federici documents similar communalizations of domestic chores occurring in Peru, Argentina, Venezuela, and other beleaguered countries.

Her vision of social change is about as far from reformism as you can get. So many leftists are concerned with the questions of who will own what in the future. Will the economic system be controlled and owned by the capitalists or the working class?

For Federici, interested in the sustenance and re-establishment of the commons, the question to be asked for the emergent, commoned world is not who owns what, but is this owned or not owned? As she points out, “Commons are defined by the existence of shared property, in the form of shared natural or social wealth.”

As Peter Linebaugh highlights in his insightful Foreword, Federici recognizes the importance of fighting for the strengthening of non-owned social wealth and shared social life.

Shifting geography to the U.S., one can see the 2011 Occupy movement as a momentary beachhead in the drive for a genuine commons, with its sharing of food, labor, learning and voices. Federici brilliantly compares the value of the Occupy commons to the pseudo commons of the Internet, which is basically privileged property for the relatively well off, its computer instruments the products of abused, sweated labor.

Federici points to two of the central arenas for social struggle happening now: first, that of reclaiming or holding communal lands, urban gardening being part of this, and the shifting of domestic, privatized chores into jobs done together by neighborhood, communal networks; and, second, the linking of these struggles—city by city, region by region.

Re-enchanting, in Federici’s parlance, means returning to a world of shared, unowned social wealth and land.

Jim Feast is a frequent contributor to the Fifth Estate. His wife, Nhi Manh Chung, wrote “The Pool at the Sak Woi Club,” in FE #394, Summer 2015, which is included in the just-published, Among the Boat People: A Memoir of Vietnam, available from Autonomedia. autonomedia.org