By Ralf Ruckus

naoqingchu.org

September 10th, 2019

This article is the result of recent discussions with protesters and left-wing activists in Hong Kong. It gives a short overview of the escalated confrontation and argues that the broad ignorance of the global left is a mistake. Despite its limitations, the movement constitutes a major challenge for the right-wing regime of China’s Communist Party (CCP) and could be the prelude for more struggles against the capitalist relations in Hong Kong, the People’s Republic of China, and elsewhere.

Massive demonstrations, rallies, violent clashes, tear gas and water cannons, burning barricades, attacks on police stations, blockades of streets and subway lines, strikes, and more – these are the dramatic forms of the current mass movement in Hong Kong. It expanded in June 2019 in reaction to a planned extradition bill which would have allowed handing over alleged criminals to mainland China’s repressive forces. Until September, the movement has escalated into the most serious social confrontation in Hong Kong since the riots against British colonial rule in 1967. And, as Hong Kong has been a semi-autonomous part of China with certain ‘democratic freedoms’ since the city was handed over by Britain to China in 1997, the escalation of the conflict also constitutes a serious challenge for the CCP regime.

Western politicians (and mainstream media critical of the CCP) describe the movement simply as one “for democracy and freedom” – and even ignore its violent tactics or call it simply a reaction to police violence. They see China’s global expansion politics as a threat to their own economic and political interests and want to use this chance to weaken China’s position and influence. The Western liberal and institutional left repeats the “democracy and freedom” hymn in the same way it usually defends the interests of national capitalist regimes using human rights arguments. That a part of the orthodox left has expressed support for the position of the CCP regime, instead, is also no surprise considering its outdated ‘anti-imperialist’ reflexes and lack of understanding of the capitalist nature of the CCP.

The important question is why the anti-capitalist left has been largely silent and inactive regarding the escalation of the conflict in Hong Kong. Is it being blinded by the mainstream reporting and does not want to support a mere ‘democracy’ movement? Is it believing the claims of orthodox leftists that China is still ‘socialist’? Is it deterred by the nationalist and racist discourses or requests for help from the U. S. government of parts of the Hong Kong movement?[1] Or is Hong Kong – which has no long history of bigger and explicitly left-wing political movements – simply outside the radar of the anti-capitalist left and ‘too far away’ to even bother?

The point to be made is that the current confrontation between the protest movement and the governments in Hong Kong and China constitutes an important historical rupture. A look at the different phases of the movement’s development reveals that it a) has come up with radical forms of movement and struggle, b) has broken the existing social consensus on the relation of Hong Kong’s population, government and police, and c) threatens to destroy Hong Kong’s role for China’s (and global) capitalism.

The outcome of the confrontation is still open, but the anti-capitalist left should thoroughly analyze the development and support those currents within the movement that have a progressive potential.

Phases

The movement in Hong Kong makes use of the experiences of previous mobilizations since the handover in 1997, namely the Umbrella Movement in 2014 when tens of thousands demanded “free elections” in Hong Kong from China’s regime and occupied a large space outside Hong Kong’s parliament for several weeks – before they were pushed aside without having reached their goal.

The first phase of the current mobilization began in February 2019 with the Hong Kong government’s announcement of the extradition bill. A public outcry and several peaceful demonstrations followed.

As the government did not stop the proceedings to introduce the bill, a second phase started on June 9.[2][3] Several mass demonstrations with up to two million participants in the center of Hong Kong[4] – surprising if we consider a city population of just 7.5 million – were followed by major clashes with the police using tear gas, rubber bullets, and bean-bag rounds against demonstrators building barricades and throwing objects at the charging police forces.[5] The Hong Kong government suspended the bill on June 15, but without withdrawing it.[6][7] By then, the Hong Kong government had already lost all the trust of large parts of the Hong Kong population.

The movement formulated five demands: 1) the complete withdrawal of the extradition bill, 2) the withdrawal of the ‘riot’ charge against protesters, 3) the release of arrested protesters and the drop of charges against them, 4) an independent inquiry into police violence, and 5) the implementation of genuine universal suffrage (sometimes also the resignation of Hong Kong government leader Carrie Lam). The second phase ended on July 1, when during a large demonstration hundreds of militants broke into the parliament building and ransacked it.

In the third phase, the movement decided to spread to other city areas. These actions were meant to take the protests to other parts of the Hong Kong population but also to outreach to mainland visitors and immigrants to explain the movement’s demands.[8] They drew smaller numbers as before until the situation changed again on July 21, when hundreds of men in ‘white shirts’ from local (pro-CCP) triads attacked and injured homecoming protesters in a suburbian subway station. The obvious collaboration of police and triads during the attack led to public outrage.[9] The police itself became the focus of anger and hatred of large parts of the Hong Kong population, and a spiral of increasingly violent action and counter-action began. Surprisingly, the violent attacks by protesters on the police have so far been supported (or, at least, tolerated) by the bigger part of the movement as it became obvious that the government hardly reacted to ‘peaceful’ demonstrations.[10][11][12]

The protesters further changed tactics using ‘flash mob’-like actions by blocking roads, setting up barricades, etc. in one part of city, then using the subway to move to other parts to do the same there, always trying to be ahead of the police – a tactic self-described as “be water” (referring to a Bruce Lee quote).[13] Meanwhile, the police upgraded its equipment and tactics, with more protective gear,[14] new weaponry, undercover cops posing as protesters,[15] and more flexible and aggressive attacks. The height of this phase was August 5, when a strike call was followed by hundreds of thousands, the subway was brought to a halt, and mass demonstrations including coordinated attacks on several police stations took place.[16][17][18][19] Then the demonstrators shifted their attention to the airport, a central and economically important traffic hub not just for the city but for the whole region. It was partially shut down on August 12 and 13.[20]

The forth (and ongoing) phase began with the movement’s decision to halt the violent clashes and regroup its forces. Peaceful demonstrations on August 17 and 18, the latter with 1.7 million participants,[21] showed the still massive support of the movement, as did the human chain action (inspired by a similar action in the Baltic states in 1989) of several hundreds of thousands on August 23.

As the government still made no concessions, the violent clashes have returned on August 24 and after. The police have ordered the subway authority to shut down stations in protest areas, continued to use tear gas, rubber bullets, and brutal baton attacks, and recently started to employ water cannons.[22][23] The protesters have used Molotov cocktails, set fire to barricades,[24] ransacked subway stations,[25][26] and blocked train services and roads to the airport.[27][28] On September 2, university and high-school students returned to school after the summer break and started strike actions.[29][30] On September 4, Carrie Lam actually fulfilled the first demand and withdrew the extradition bill,[31] but so far that has not stopped further clashes.[32][33]

Why did the movement escalate from peaceful marches to bring down a bill to a massive and partially violent movement that targets the police, the position of the Hong Kong government, and the influence of the CCP regime? When Britain and China agreed on the handover and formulated the “Basic Law” as the constitutional document that defined China’s ‘one country, two systems’ rule after 1997, people in Hong Kong and elsewhere believed that it was China that would change and become more democratic in the course of its industrialization, urbanization, and integration into the world-economy. Instead, China has not moved into that direction but has not only tightened its authoritarian repressive rule but also amplified its economic and political interventions in Hong Kong.

Today, many people in Hong Kong expect that China will not even wait until 2047, the official end of the ‘one country, two systems’ arrangement. The extradition bill was seen as just one more threat to the relative freedoms of expression and association and the Western style ‘rule of law.’ Protesters see their struggle as an ‘end game,’ the final chance to stop a full takeover and the introduction of an even more repressive regime by China.

Besides, many people in Hong Kong, especially young people, suffer from the immense social inequality in the city, the high rents and relatively low wages, the competition of mainland immigrants for jobs, housing, and welfare.[34][35][36] They feel that China’s increasing influence will further worsen their economic situation unless they stop it.

Organized Struggle

At least a third of Hong Kong’s population (2.5 million people) have actively taken part in the movement – probably a world record. The movement is heterogeneous, with people of different ages, genders, social positions, and professions involved: high-school and university students, white collar workers, civil servants, airport workers, nurses, and many more. According to surveys, most of the participants are highly educated and rather ‘middle class’ but many blue and pink collar workers are also taking part or simply support it but cannot participate much due to economic pressures and long working hours. Actually, many protesters live in two worlds, a full work schedule during weekdays, and the rebellious movement on the street in the evenings and on weekends.[37] Notable is the general absence of the city’s hundreds of thousands of immigrant female domestic workers from the Philippines and Indonesia.[38]

The masses of participating young high-school and university students grew up in post-1997 Hong Kong and never developed a ‘Chinese identity.’ They fear the repressive CCP system and want to keep their Hong Kong ‘way of life.'[39] Meanwhile, many of the older protesters are migrantsfrom the mainland or their descendants who suffered from CCP purges or other campaigns before they came to Hong Kong in the past decades. They don’t trust the CCP.[40]

The protesters are confronted by a smaller part of the population that does, indeed, supports the Hong Kong government and police as well as the CCP and has staged own demonstrations with up to tens of thousands of participants.[41]

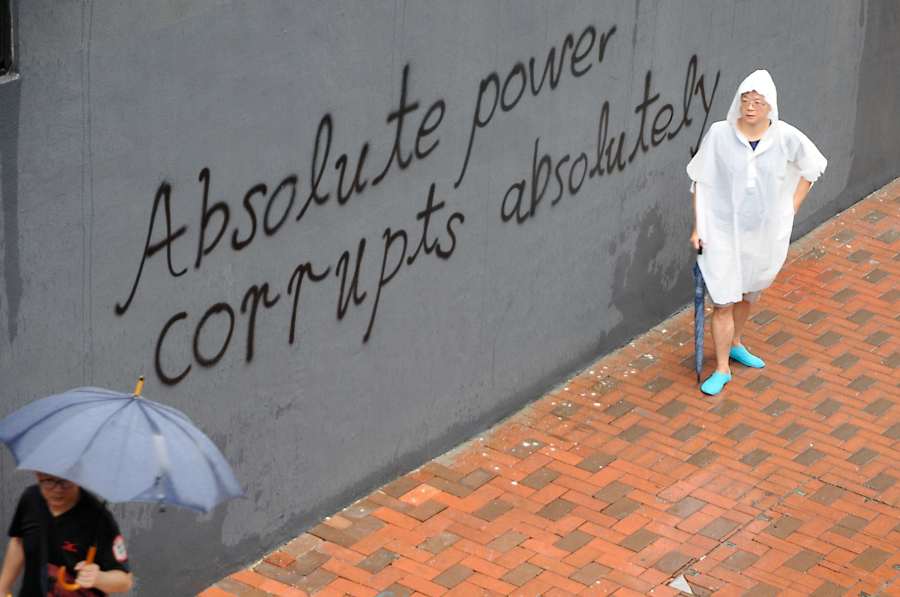

The protest movement shows an amazing ability to self-organize, develop and change strategies, and make decisions – despite its massive size.[42][43][44][45] Debates and actions are often organized through forums like (Reddit-like) LIHKG,[46][47] Telegram and Facebook groups, as well as other digital tools.[48][49] Sometimes thousands or ten thousands of members use these chat groups, and even decisions on the next step during a demonstration are made using apps. During peaceful and violent actions, people take over certain functions: front-line fighting, building barricades, providing supplies like masks or helmets, offering medical treatment, etc. Others administer the digital communication tools, post information on the location of police squads or PIN-codes for doors in the neighborhood for people to escape, provide visual art work related to the movement, and take care of the ‘Lennon Walls'[50] – posters, stickers, photos, etc. put up on certain walls. Many people also use their own money to buy water, food, subway tickets, or equipment like gas masks and distribute it to demonstrators, or they donate money if they have no other way to support the movement.

Striking is the absence of leaders and the weak position of political parties.[51][52] For the CCP leaders and the Hong Kong government, this is hard to believe.[53] They, as well as Western media, present people from certain ‘democratic’ or ‘localist’ parties (who played a role during the Umbrella Movement) as today’s leaders or representatives, but those are hardly important for the current movement. This absence of leaders is partly a result of the repression after the Umbrella Movement because many outstanding figures were charged and got prison sentences. Another reason are the divisive tactics of Umbrella Movement leaders like those from ‘localist’ (nationalist) groups. There is a wide consensus that leadership conflicts and divisions weakened the Umbrella Movement and should not be repeated.

So the current movement is mostly pushing for the five demands and uses general slogans like “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times” or “Hong Kong, go forward.” More issues have frequently been voiced and discussed, e. g. left-wing demands regarding social inequality or right-wing demands regarding the limitation of mainland immigration or Hong Kong independence. However, the movement stays with the five demands to ensure its unity and push through these common demands first.

China’s Interests

The Hong Kong government under Carrie Lam is visibly shaken by the movement but has largely remained in the background. It is clear that the decisions on how to deal with the movement are made in Beijing. After the CCP did not allow any public reporting in mainland media at first, it later changed its course and started to push a nationalist media campaign[54][55][56] that portrays the protesters in Hong Kong as “criminals” or “terrorists”[57] who are driven by “foreign black hands” and pursue a “color revolution” against the CCP and China’s national interests.[58][59][60][61][62] Chinese state media and government representatives have threatened a direct intervention of Chinese security forces,[63][64][65][66][70] and Chinese anti-riot units of the People’s Armed Police organized public drills in Shenzhen, close to the Hong Kong border.[71][72] The CCP regime also uses its economic power and put pressure on companies like the airline Cathay Pacific after its employees had openly taken part in protest actions.[73][74][75]

The CCP regime wants to undermine the protesters’ legitimacy and weaken the movement as it looks to protect its political and economic interests. Hong Kong plays a vital role for China[76][77] as well as Chinese and foreign companies as a transitional hub for capital inflows and outflows, investments, and connected financial and legal services. The city is able to play that role because of its special political status, its own currency, and its Western legal system.[78][79] The protests as well as the ongoing Sino-U.S. trade war already take a toll on Hong Kong’s economy.[80][81][82]

Any direct intervention by the People’s Armed Police or even the army could destroy Hong Kong’s economic function and bring massive economic losses. However, a continuing movement that openly challenges China’s rule in the city and demands more autonomy or even Hong Kong independence undermines the CCP’s authority and could even prove contagious and provoke more social uprisings in China.[83] Despite the CCP propaganda and the nationalist mobilization in China against the Hong Kong protests, mainlanders do, indeed, have different perspectives on the movement.[84]

Therefore, the CCP leadership wants to quickly stop the movement (and the spreading of pictures of burning barricades), at least not later then the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 2019.[85][86] That might not be possible without increased repression and the direct intervention of Chinese security forces. The CCP regime is nervous as the and the escalation of the conflict and the inability of the governments in Hong Kong and Beijing to contain and stop it has already led to speculation about a weakened position of the CCP’s leader Xi Jinping.[87]

Limits and Potentials

Leftists have shown apparent difficulties in dealing with recent social movements that don’t fit into their expectations, that refuse to be led by leftist representatives, and that include elements that voice politically problematic positions and demands, as, for instance, the Yellow Vests in France and now the movement in Hong Kong.[88][89] However, the latent racist positions of parts of the Hong Kong movement and its blurred and problematic demand for ‘democracy’ (or for the defense of the status quo) should be a reason for left-wing activists to get involved, resist those positions, and support the movement’s progressive currents – as some in Hong Kong already try to do.

The current movement in Hong Kong is surely one of the most amazing mass mobilizations seen in the past decades. After all, for the CCP it is the biggest challenge by popular protests since the Tian’anmen Movement in 1989 – even if this comparison has its limits due to the changes in China and globally since.[90] It also comes close to some of those during the ‘Arabellion’ in 2010 and 2011.

The movement is, indeed, no anti-capitalist mobilization, yet, but it has questioned the position of the capitalist class that governs (and virtually owns) Hong Kong as well as that of the rulers of the CCP in Beijing. The attacks on the police show that many in the movement have no trust in core state institutions. Strikes and other mobilizations in workplaces (hospitals, the airport, schools and universities, the public sector, etc.) further undermine the acceptance of capitalist relations, or, like one protester said: “Workers don’t work as hard as usual and speak up against managers now.”

What will happen next? In a pessimistic scenario, it could end up just like most of them, in a crackdown and defeat, as the Hong Kong government is already talking about declaring a state of emergency,[91] and the CCP seems unable to find a smooth solution[92] and might mobilize its security forces to crush the movement.[93][94][95]

In a less dramatic scenario, the movement might just run out of steam. In that case harsher repression measures and many more arrests are still likely as they already have begun.[96][97][98] At least some of the ‘democratic freedoms’ in Hong Kong might be kept, which could be seen as a success of the movement. Many in the Western left underestimate the importance of these ‘freedoms’ for organizing resistance and social movements. So far, Hong Kong has been a haven for labor groups, feminists, and other left-wing activists who have used the city to organize activities across the border in China, and any serious crackdown by the CCP regime in Hong Kong could mean they have to stop.[99]

In an optimistic scenario, the movement could be the beginning of a rebellious generation and further social struggles.[100] The underlying social issues that large parts of the population face (high rents, low wages, long working hours, social inequality, low quality of health care, etc.) could spark anti-capitalist currents, and the experience of collectively standing up and struggle against powerful state authorities might be just the start of more struggles to come that question the capitalist relations as such. That could trigger similar movements in mainland China which face the same enemy – the right-wing CCP regime that has been at the center of the capitalist restoration in China for decades and engaged in a highly repressive drive against left-wing activists in the past few years.[101]

Much depends on the limitation the CCP’s influence in Hong Kong and the containment of the right-wing ‘localists’ and their nationalist and racist polices in the city. The involvement of left-wing activists, the promotion of anti-capitalist topics and debates, and even the support from left-wing movements abroad[102] could play a decisive role in making the last scenario more likely.