Notes From the Underground

By Jessica Freeman-Slade

[tk] reviews

Issue VI, October 2010

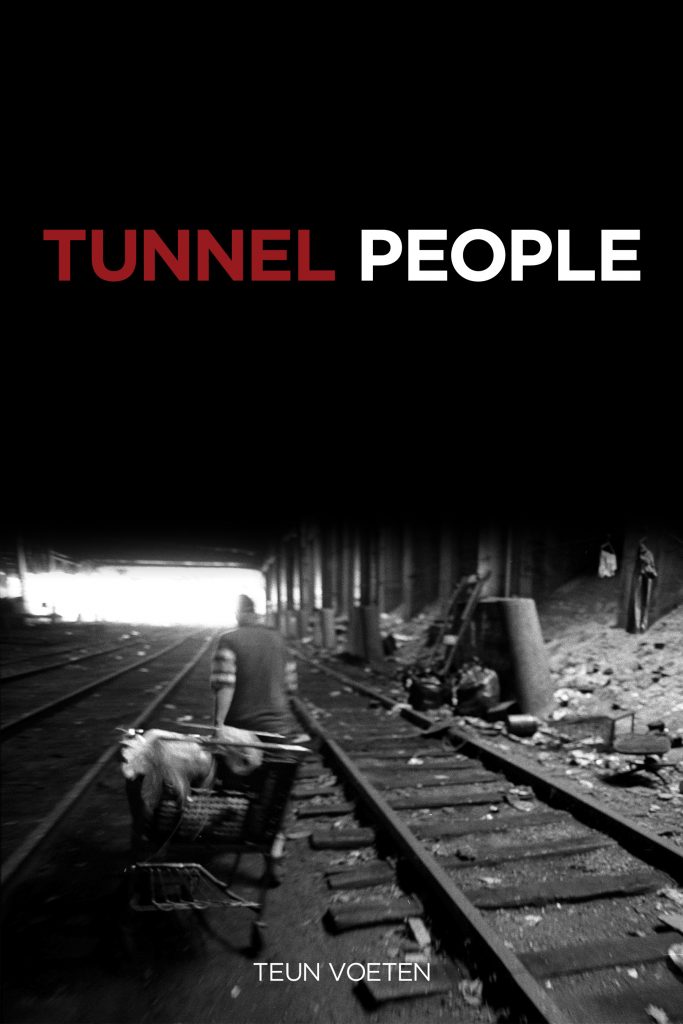

When in 1906 the journalist Upton Sinclair released his novel The Jungle, critical of unsafe labor as well as meatpacking practices, he found himself disappointed by its reception: reform came not for the workers, but for the meat. Sinclair discovered readers were more interested in the bestseller’s exposé of unsanitary meatpacking practices than its searing portrait of the horrors of factory life; he noted, “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.” When faced with exposés such as Sinclair’s, or Teun Voeten’s Tunnel People (PM Press, $24.95), it often proves less difficult for readers to stick with the unsightly details than to confront the book’s larger, more terrifying issues. Yet in Voeten’s book, whose central focus is the humanity of the tunnel people, it is impossible, dishonest, and ultimately the reader’s loss, to look away.

First published in Amsterdam in 1996, and now available in its first American edition, Voeten’s book details his experiences of cohabiting and corresponding with the residents of New York’s Amtrak tunnels from 1994-1996. Beneath Riverside Park, Voeten is led through the underground by a handful of guides. Its denizens become as familiar as family: most memorable are the affable Bernard, “New York’s most famous homeless man,” and the poetic Julio, who defends his albums of Beethoven, Mozart, and Tchaikovsky from marauding rats. Not every figure in this world is endearing—Voeten takes great pains to describe the ominously absent Bob, an insatiable speed addict whose vacated tunnel abode Voeten uses during his reporting, and the elusive Kool-Aid Kid, who leaves a trace of green Kool-Aid in every camp he vandalizes. Most of the people Voeten meets are far from caricatures: Frankie and Ment, two teenage boys who greet him with a baseball bat yet quickly decide to share their dinner, and Kathy and Joe, one of the few couples in the tunnel community, who carve out a domestic life in the most unlikely of circumstances.

When early stories emerged about the tunnel people they were labeled “mole people” and “CHUDS” (cannibalistic human underground dwellers). As Voeten notes, “There were urban legends about subway maintenance workers who had disappeared without a trace, having met their final destiny on the roasting spits of starving savages.” Yet Voeten’s subjects are anything but monsters, or even case studies: they are his neighbors. Voeten is humane and sympathetic at every level of his reporting, never patronizing, always aware of the choices these people have made. (Though he does not shy away from identifying the crack and heroin users in the bunch, he never attempts to change their stories or convince them to quit.) These are vibrant, funny, and often deeply self-aware people, cognizant that their situation is one they’ve created for themselves. Bernard, a philosopher to his very core, says, “One thing made me really sad—in the tunnels I never encountered a real human that accepted his fate. Most people here allow their past to haunt them. . . . I never saw here any spiritual growth.”

Voeten’s extraordinary tunnel photography demonstrates the macabre, labyrinthine quality of these quarters and this life, but nothing in his portrait is sugarcoated. Voeten details the disparity between what he found in portrayals of the homeless by mainstream media and reality:

The slapdash folder of the Coalition mentions that:

• One out of five homeless people has a job but cannot afford housing.

• One out of three homeless is a veteran.

• Women and children are the fastest growing segment of the homeless population.

From my own experience and from what the tunnel people have told me about their fellows, combined with data from sociological research and literature, I reach different conclusions:

• More than fifty percent of all homeless have some kind of criminal past, are on parole or are fugitives.

•

Most homeless who say they are veterans have hardly seen a

battlefield, or have been discharged from the service for all kind of

reasons.

• Ninety-five percent of the money you throw in that paper cup will be spent on crack.

It’s

hard to read this book without getting mired in the thought that

hundreds of thousands of people today have recently begun to think of

themselves the way the tunnel people do—as on the fringe, better off

scavenging for what they can get, with nothing significant on the

horizon to keep them afloat. In light of the recession’s effects, and

with the number of homeless families skyrocketing, tunnel life still

seems a viable alternative to life on the increasingly crowded streets.

As Voeten notes, then as now, it is nearly impossible to get a real

sense of the homeless population—“families who are camping out in the

highly crowded rooms in welfare hotels but still have some privacy are

technically not homeless. The alcoholics who live in cheap motels in

rooms of thirty square feet, or the poor black families who are cramped

into squats are also not considered homeless. Overlooked in most studies

and surveys are the ‘couch people,’ those who have lost their homes and

are staying on the couches of friends or relatives.” In a study

conducted in 2009, the Department of Housing and Urban Development found

that on a typical October night, there are as many as 730,000 homeless

people on the streets. That’s up from the 1996 statistic of 444,000

people, the year Voeten concluded his research. There’s nothing to

suggest that the problem is abating—if anything, it’s exploding. And

though the tunnels may have closed, their former residents seemed to

anticipate this problem. “Bernard gazes up toward the grate. ‘Here it

was a Heaven of Harmony. It became a Heaven of Headaches,’ he says

dramatically. The sunlight falls down and lightens up his silhouette

against the dark tunnel walls. With his high forehead and bald patch,

his straight nose, and his powerful chin he looks like a stern prophet

from the Old Testament. ‘But who am I to complain about chaos? Even God

has to accept the existence of chaos.’”

In the summer of

1995, the tunnel people were evicted by Amtrak, once seemingly

unconcerned so long as the trains continued to run on time. With the

American edition, Voeten has added an epilogue updating us on his main

characters. Some have restarted their lives, kicking drug habits and

finding apartments through the Housing Works program. Others have died,

horribly, of AIDS, violence, and continued exposure to street

conditions. And some are still roaming, their whereabouts unknown. It is

hard to know if any of the many reporters covering the tunnel people

invested as much as Voeten in these people’s futures, “canning” with

them, defending them against investigations by social services, and even

smoking crack with them. Voeten’s journalistic objectivity can be

questioned, but not his commitment to this story and these people. He

seems to understand, perhaps better than his readers ever could, just

how much these underground safety nets can mean to the people who

benefit from their shelter. But more importantly, he has found a way to

show us the tunnel people not by their statistical trademarks—drug

addiction, alcoholism, crime, and AIDS—but rather through their

humanity, their talents, their extraordinary attitudes of good humor and

hope.