By Luke Koz

Working Class Magazine

Issue XII: The Outlaw Issue

As a war photographer, journalist and anthropologist, Teun Voeten has courted extreme circumstances. For How de Body, he traveled to Sierra Leone to report on child soldiers just in time for a ceasefire to end, leaving him stranded in the Bush, hiding from warring rebels. His work in progress focuses on the drug war in Mexico. To write it, Voeten’s spent much of his recent time in the most dangerous areas of conflict. His A Ticket To is a catalogue of his experiences through photographers, featuring images from conflict zones throughout the world. War has featured prominently in most of his work.

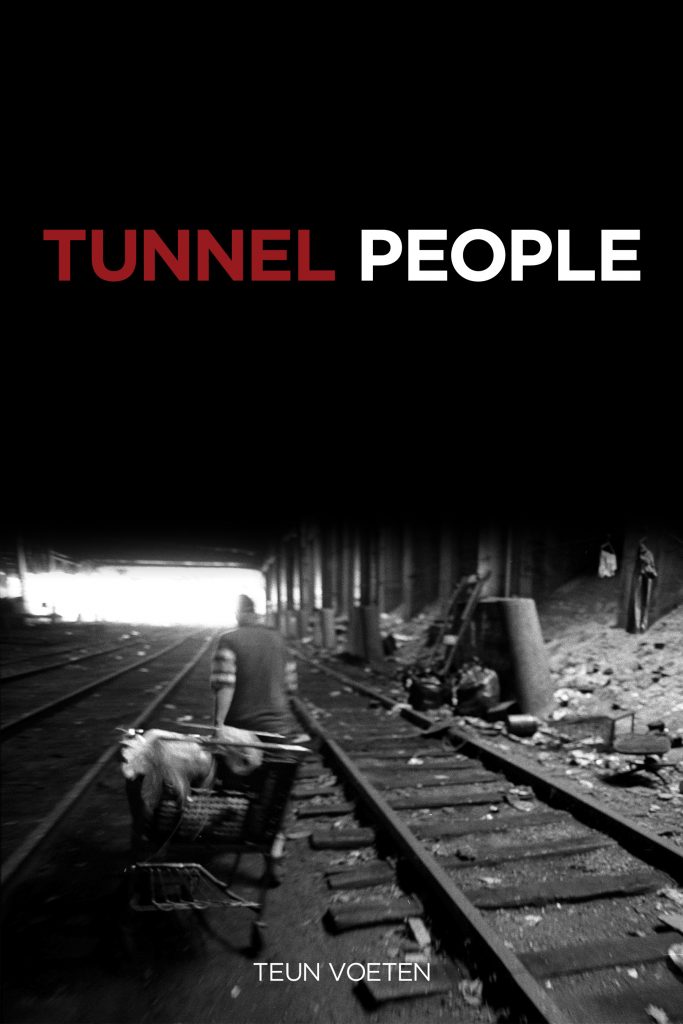

However, war does not factor into one of Voeten’s most enduring works, Tunnel People, though extreme circumstances do. In the book—recently translated, updated and reissued by Oakland-based publisher PM Press–the anthropologist chronicles his time spent underground during the mid-1990s in New York City’s tunnels. Over five months, Voeten photographed, studied, interviewed, and became part of a small group of homeless people who decided to live in the tunnels beneath the City.

Working Class caught up with Voeten at The Half King, where he was scheduled to read from Tunnel People. However, rather than a reading, Voeten treated his audience to a photograph showing and interview session that more closely resembled a director’s casual Q&A than a formal event. He shared anecdotes about Bernard, one of the central figures in Tunnel People, and discussed some lessons he learned living in the tunnels (short version: don’t leave a bag of cookies in your rat-prone bunker). He spoke with humor and an earnest energy one would think impossible for someone who has spent decades documenting war zones. We spoke with Teun about his work, his approach and the update of Tunnel People.

WC: So, we hear you’ve been working in Mexico lately, correct?

Teun Voeten: I’m working now on a new project. It’s about the drug violence in Mexico.

WC: Where specifically in Mexico have you been?

TV: The Northern part, the border with Texas, Ciudad Juárez, Culiacán, Michoacán, many states—basically, the hot spots in the war on drugs, though actually the whole country is influenced by it.

WC: Where does the violence take precedence?

TV: It takes place on the Mexican side. Ciudad Juárez for example it borders El Paso. El Paso had like three killings in a year while Ciudad Juárez had thousands.

WC: Is it fair to say your work showcases an embedded or personally integrated approach?

TV: You could call it embedded or you could call it anthropological. I’m basically an anthropologist. Actually, I just interviewed a friend of mine who has been embedded with the military for a book. I asked him, “is this journalism or anthropology,” because of the integration. You see, anthropology is a science, and journalism and science are the same, except a journalist presents findings in an easy to read way. But journalism is founded on research and observation [like science]. In anthropology, there is also participant observation, in which you act like one of the group—or become one of group.

WC: Does the anthropological approach account for your voice?

TV: Well, that’s also my personal style. I wrote a book about Sierra Leone and it was basically following my own personal experience when I was nearly killed. It’s good to structure a work around your own experiences. Although I do think your own experiences should be put in perspective, because it’s a book about other people. I’m not writing about myself, but I’m writing about a situation in which I’m a participant.

WC: Tunnel People, even though it’s a fundamentally different subject from war, there seems to be similarity. What attracted you to that subject?

TV: I have an interest in people living and surviving in extreme circumstances at the edges of the human condition, be it in a war zone or be it in a tunnel. I’m also interested in sociopolitical phenomenon and of course war is a sociopolitical phenomenon and poverty is another.

WC: It’s been over a decade since you wrote Tunnel People, yes?

TV: It’s been thirteen years and I’ve now done the update.

WC: How was going back to it? What did you do for the update?

TV: Last year, I was able to track down most of the people I mentioned in my book. Actually, with Bernard, the main character, I was still in touch with him. He is a smart, funny guy.

WC: He was sort of like the mayor of the underground in a way …

TV: Yes, but it’s a little bit relative. He was one of the most intelligent and eloquent individuals I met there.

WC: How is he?

TV: He’s doing fine. Today is his birthday. We’re going to have lunch tomorrow. He has been working at the Parks Department and he’s getting his degree to become a security guard. He’s taking care of his sick father. He has strong ties with his family and he’s never broken with his family: his mother, his brothers, his children. He was a little bit of an exception. He has it well together. He stopped doing drugs. Once in a while he has a beer and that’s it.

WC: It’s been thirteen years, for some reason it seems people keep returning to Tunnel People. What do you think explains it?

TV: People have a huge fascination with homeless people living underground in one of the wealthiest cities in the world. When I wrote the book, New York was high amongst the very most expensive cities. Right now, Abu Dhabi, Tokyo, and Moscow might be more expensive. It’s very fascinating though that homeless have literally become invisible in such a place. It’s a very telling metaphor. And of course, people love creepy New York stories. There was that book, The Mole People. It was very sensational and not so accurate, but it’s still a bestseller. Or this for example: my friend Marc (Singer) made a movie, Dark Days, and people are still seeing that movie and they love it.