By Chris Lanier

The Comics Journal

Was Flood! your first book-length story?

It was my first attempt at “writing” an entire novel in pictures. I’d drawn many shorter stories—some with words, some without. I wanted to see how epic a tale I could tell silently—without resorting to words. Flood! was partly autobiographical: a man living with his cat, in New York City, in the last days of the twentieth century.

You don’t want to slight the cat—he plays an important role at the end of the book.

[Laughs] I had this black cat named George, who kept me company while I drew the final chapter. He ended up being the hero of the story. The book’s three chapters were created during three different periods of my life—over a seven-year span. I began drawing the first chapter, “Home,” in my mid-twenties as a one-shot experiment. I had no idea it would later become a chapter in a longer saga.

Where was “Home” first published?

I self-published it as a pocket-sized booklet, folded and stapled by hand, in an edition of five hundred. I brought them around to several bookshops in lower Manhattan, who took them on consignment. Three years later, I self-published another wordless tale, “L,” in an edition of a thousand—again without any notion that it would wind up a chapter in a longer book. (Heavy Metal and World War 3 Illustrated ran chapters as I completed them.)

And the artwork—it’s all scratchboard, right?

Yes, scratchboard, a technique akin to woodcut. It’s a subtractive process: the ink was already there, and I scratched it away with a razor blade.

When Flood! was first published in 1992, there wasn’t anything quite like it out there. The idea of the “graphic novel” hadn’t really taken off in the bookstores yet—and the fact that it didn’t have any words, that it was in fact purely “graphic,” also set it apart.

The term, “graphic novel” took several more years to catch on. Bookstores didn’t know what category to put Flood! in. Some shelved it with the Fine Art books, others with Humor, or Pop Culture. Sometimes it wound up in Science Fiction . . . while Barnes & Noble actually placed it in their Psychology section!

[Laughs] Well, there might be some logic to that. During the dream sequence in Chapter 2, you seem to be wrestling with Jungian Archetypes or images.

That chapter was dreamed up in Amsterdam, while living on a houseboat with my Dutch girlfriend. One night I was exploring her boat, and found an old copy of Man & His Symbols, by Carl Jung. I read it cover to cover, and realized that, since I wasn’t using words, it was important for me to develop a deeper understanding of the language of symbols.

Could you talk a little more about the symbolism of the subway in that chapter?

The subway, to me, represents the unconscious state of the masses, who race through underground tunnels, speeding backward and forward in time.

And significance of the title, “L”?

The “L” train runs below 14th Street—the street I grew up on. It’s a strange subway line because it runs underneath the other trains—its tracks are on a deeper level underground. Every line in Manhattan runs North-South, but the L train runs crosstown—East-West. It’s was also the most dangerous line . . . with the highest crime rate in the system.

How much of the book is autobiographical?

Personal experience was my starting point. I’d recently worked a stint on a factory conveyor belt, and my head was still throbbing. So the first chapter, “Home,” is about a worker who goes to the factory one day—only to find the plant closed. In the second chapter, “L,” the protagonist starts to resemble yours truly. By the time he climbs out of the subway in the last chapter—and sits down at the drawing board—it’s clearly the artist himself. Typically, an author’s first novel will be autobiographical because, hey, this is all he knows—his own experience.

“Write what you know,” as the saying goes.

But I approached my second novel in pictures quite differently. In Blood Song, I wanted to tell the story of someone totally opposite from myself—someone coming from an entirely different time and place. At the beginning of the tale, it’s unclear if we’re even in the present . . . until helicopters appear on the horizon.

Blood Song was your first extended work where the main character isn’t a self-portrait in some way . . .

Yes, it was a total departure . . . I was no longer drawing from personal experience. The protagonist of Blood Song is a girl, living in the jungle with her dog. The story is a leap of imagination. I’ve never even had a dog—so I’m already on shaky ground here [laughs]. I studied canine body language, because the dog is a major player in the story, it’s all witnessed through his eyes. In many ways, the dog is the secret hero of Blood Song.

In Flood!, your cat emerges as the sole survivor . . .

Yes . . . he’s the Ishmael of the story.

Who is the barefoot woman we see toward the end of Flood!, preaching silently to the crowd?

She looks familiar doesn’t she?

Yes . . . I was wondering if you’re making a deliberate connection to the heroine of Blood Song.

[Laughs] Of course, she’s a bit younger in Blood Song, having just arrived in the big city. When she appears in Flood! she’s older and tougher.

The way you draw skyscrapers, they don’t necessarily seem to be inhabited. They seem almost like monuments to something. One thing I found interesting in Blood Song is that when the main character arrives in the city, even though the panels at that point start to get smaller, which is a reflection of a feeling of claustrophobia, you still have this sense of the monumental space of the skyscrapers. And I wonder what sort of aesthetic strategies you’ve developed to contain this monumental cityscape on the panels and the page . . .

The city is so massive that I always approach it in relation the human figure. To convey the city’s monumental scale, it’s best to contrast it with small, flesh-and-blood characters. I employ this device often in my cover paintings for the New Yorker magazine.

Let’s get into some family background . . .

I’m a third-generation New Yorker, born and raised on Manhattan Island. My grandmother was born on the Lower East Side, where I lived most of my life. My mother was born and raised in the Bronx. My parents never owned a house; we lived on the seventh floor of an apartment building. My brother and I grew up in the same room, and damn near killed each other a couple of times . . . we needed more space. So, I’d escape from it all by spending long hours up on the roof. No one was ever there. In the evening, when the sun went down, I’d watch all the skyscraper windows light up . . . and the entire city would be mine.

And you went to art school in New York as well.

I won a scholarship to the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art.

Your grandfather was an influence on you, in pursuing art . . .

My grandfather introduced me to silent storytelling when I was a boy. He showed me several “woodcut novels,” which were popular in the 1930s, when he was a young man. None of the books had any words in them, only stark black and white images. I was very close to my grandparents, who lived up in the Bronx. My grandfather loved art, and was a good draftsman, but never did it for a living. He’d often take me to the movies up on Times Square when I was a kid. This was the old Times Square, before Disney took it over . . . a different world.

What woodcut novels did your grandfather show you?

When I was about twelve, he gave me two wordless books, Passionate Journey, and The City, by Frans Masereel, the Belgian Expressionist. He said, “Take a look at these books, they’re written without using any words.” I was intrigued, but could hardly penetrate the books. They were too serious . . . not cartoony enough—or linear enough—for me to grasp. My short attention span was, no doubt, the result of television. But over the years, I’d occasionally crack these books open and marvel: “Hmm . . . entire stories told in pictures—in woodcuts no less!” Each year they affected me more and more . . . until I began to feel haunted by these silent books. In my early twenties, I began to study Masereel’s technique, and after Sue Coe gave me a huge anthology of his work, I became possessed by his vision.

Had you seen any other woodcut novels?

I’d stumbled upon a collection of woodcut novels by Lynd Ward, the American illustrator. His book, Storyteller Without Words contains all his silent stories, including Gods’ Man and Vertigo. I was deeply moved by his art, and inspired by the social realism in his work.

There’s much social realism in Flood! and we’re confronted by it in the very first chapter, “Home.”

“Home” is the story of a man who loses everything: first his job, then his lover, and finally . . . his home. The tragic theme was informed by my experiences on the Lower East Side. I’d literally climb over people to enter my apartment each night. After Ronald Reagan was elected president in 1980, a tidal wave of homelessness overflowed onto city streets, on a scale unseen since the Great Depression of the 1930s—which was when Lynd Ward was active. He published his first book, Gods’ Man in 1929, the very week of the stock market crash. Amazingly, the book sold extremely well.

So was that your main motive—to make a record of what you were seeing and the social atmosphere around you—in the way that these other artists in the past had made their own records of their times?

Partly, yes . . . I was driven by my emotional response to the changing urban landscape. I was also searching for an artistic voice—a vocabulary of my own. I studied the German Expressionists, particularly, Kollwitz, Nolde, and Grosz, who influenced the way I was rendering forms. I was using much distortion and exaggeration to show the inner turmoil of characters . . . with a dose of Dr. Seuss and R. Crumb thrown in—two brilliant influences I couldn’t avoid if I tried.

How did you support yourself during your early years as an artist?

I was a street peddler for many years. In my early twenties, I sold various things on the sidewalks of Manhattan—things I’d made by hand. For instance, I peddled these little zines I’d drawn called Communicomix. They dealt with local issues, in words and pictures, such as drugs, police brutality, and landlord terrorism—issues that were rampant in my neighborhood. Several of my earliest comic strips, and street posters, were about gentrification; real estate rip-offs, and concrete steps people could take to protect themselves.

Were you already working in scratchboard at that point?

No, this was before I picked up scratchboard. My art was pen and ink—even pencil—at first. Around the time I picked up scratchboard, I began using fewer and fewer words. In fact, “Home” was my third issue of Communicomix, and by this time I felt I’d be making a more powerful statement without words.

Did you distribute these Communicomix yourself?

I’d make them by hand, and then sell—or often just give ’em away. I’d hand them to people on the street, or simply leave ’em in public places. Phone booths for instance. I actually did this for several years, and always had to keep my eyes peeled for the police.

The police would harass you?

They’d confiscate my goods and arrest me!

That’s a good lesson in the First Amendment . . .

Anyhow, years of hustling my work on the streets proved to be educational. The School of Hard Knocks prepared me to be an assertive salesman of my own work. Many of my skills and attitudes were developed early on, by supporting myself as a street peddler on the streets of New York.

Now in addition to politics, your work draws from mythology. Could you explain what interests you about the “mythological” way of communicating?

I suppose I’m digging down to an ancient form of communication that will resonate on a pre-verbal level. My intention with Blood Song was to create a modern myth, a parable for the twenty-first century—a universal tale. I recently gave the book to a young man in occupied Gaza, who barely spoke English. His eyes immediately filled with tears as he recognized the tale of his village. Blood Song, of course, is set in an imaginary time and place.

Is the wordlessness of your novels a reaction against the kind of polyglot, “Tower of Babel” environment you were raised in?

[Pause]. . . My wordless approach is an attempt at communication despite the confusion of tongues. My neighborhood, the Lower East Side, was—by far—the most multi-ethnic part of the city. Dozens of languages were spoken: Russian, Polish, Chinese, Spanish, Arabic, Yiddish, and Italian. Korean, Japanese, Hindi . . . you name it. I felt overwhelmed by all these languages, and felt that my native tongue, English, was challenging enough. It took me a long time to learn how to read and write as a child. Even now, I find English far too difficult and complex [laughs]. So pictures are a means of communicating with people when words feel inadequate. It’s a way of bridging the language barrier.

In one sense, as you say, your silent strips are a response to the complications of language. But you’ve also talked about this kind of approach as a language in itself . . .

Pictures are a more direct language than words. Words are always one step removed, because we’re encoding what we’re trying to express into verbal symbols—which need to be deciphered. Pictures are the earliest form of writing, and drawing them is something we do as young children—long before learning to read and write. First grade was a rude awakening for me. It was a total departure from kindergarten, where we’d mess around with crayons and watercolors all the livelong day. Then without warning, things abruptly got dead serious. My teacher was a tyrant who began piling on homework. I felt a terrible pressure to learn to read and write—as quickly as possible—because everyone else was getting with the program . . . and I was slow. I always felt more comfortable drawing pictures of things. It felt more natural, somehow. Pictures are my native tongue, but words are something that I have to psyche myself into.

Do you think in images or do you think in words? Or a mixture of both?

Mostly in images . . . a bit of both, I guess. There’s a huge body of literature claiming that we think in words. Leave it to the scholars to assume that we all think in words like they do! [laughs] The linguist, Noam Chomsky, maintains that our capacity for language isn’t for communication as much as for thinking. And George Orwell makes an important point, assuming that we think verbally: if certain words were eliminated from the language, we’d lose the ability to conceive of certain ideas. His point is well taken—however I’m not completely convinced. I think he gives words too much power.

But words are powerful in our society . . .

Of course they are, but it’s possible to think in other ways—in pictures, or in music, for that matter. Frankly, I feel that our Judeo-Christian culture places undue emphasis on the word: “In the beginning was the word.” Other forms of expression—particularly images—are sacrilege. The second commandment given to Moses was: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, nor any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.” Jehova is very explicit: images are taboo.

Why do you think that would be?

Who knows? [laughs] But any governing power—be they ancient Hebrews, Vatican, or modern Corporate State—wants to control the language and images, and will feel threatened by any means of communication it can’t understand . . . or control.

So, now, on to Ginsberg . . .

In between Flood! and Blood Song, my big project was working with Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, on the book Illuminated Poems.

And Ginsberg was someone you initially met as a street peddler?

Yes, I’d often see him out there on the street. He lived just two blocks away from me. I’d say hello, and give him my latest Communicomix, which he was always enthusiastic about. He’d comment on my artistic progress. Ten years later, after he realized that I was the guy responsible for so many of the street posters around the neighborhood, he told me that he’d been collecting them. He suggested that we collaborate on a project. So, for the next three years I drew and painted dozens of illustrations of his poems, including “Howl”. Our book was one of Ginsberg’s last projects before he died in 1997. Illuminated Poems has been a perennial seller over the years, and is currently in its fifth printing.

You told me Ginsberg mentioned to you that Ward’s books influenced his vision of Moloch, in the poem “Howl.”

Yes, in Ginsberg’s own words: “I began collecting Drooker’s posters soon after overcoming shock, seeing in contemporary images the same dangerous class conflict I’d remembered from childhood, pre-Hitler block print wordless novels by Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward. Ward’s images of the solitary artist dwarfed by the canyons of a Wall Street Megalopolis lay shadowed behind my own vision of Moloch. What ‘shocked’ me in Drooker’s scratchboard prints was his graphic illustration of economic crisis similar to Weimar-American 1930’s Depressions.” Ginsberg told me that he eventually met Ward years later, and that Ward even made an engraving to illustrate the Moloch chapter of “Howl.”

Can you talk a bit about the Tompkins Square Park activism you were involved in? Because it seems to have left a real brand on your work and your subject matter.

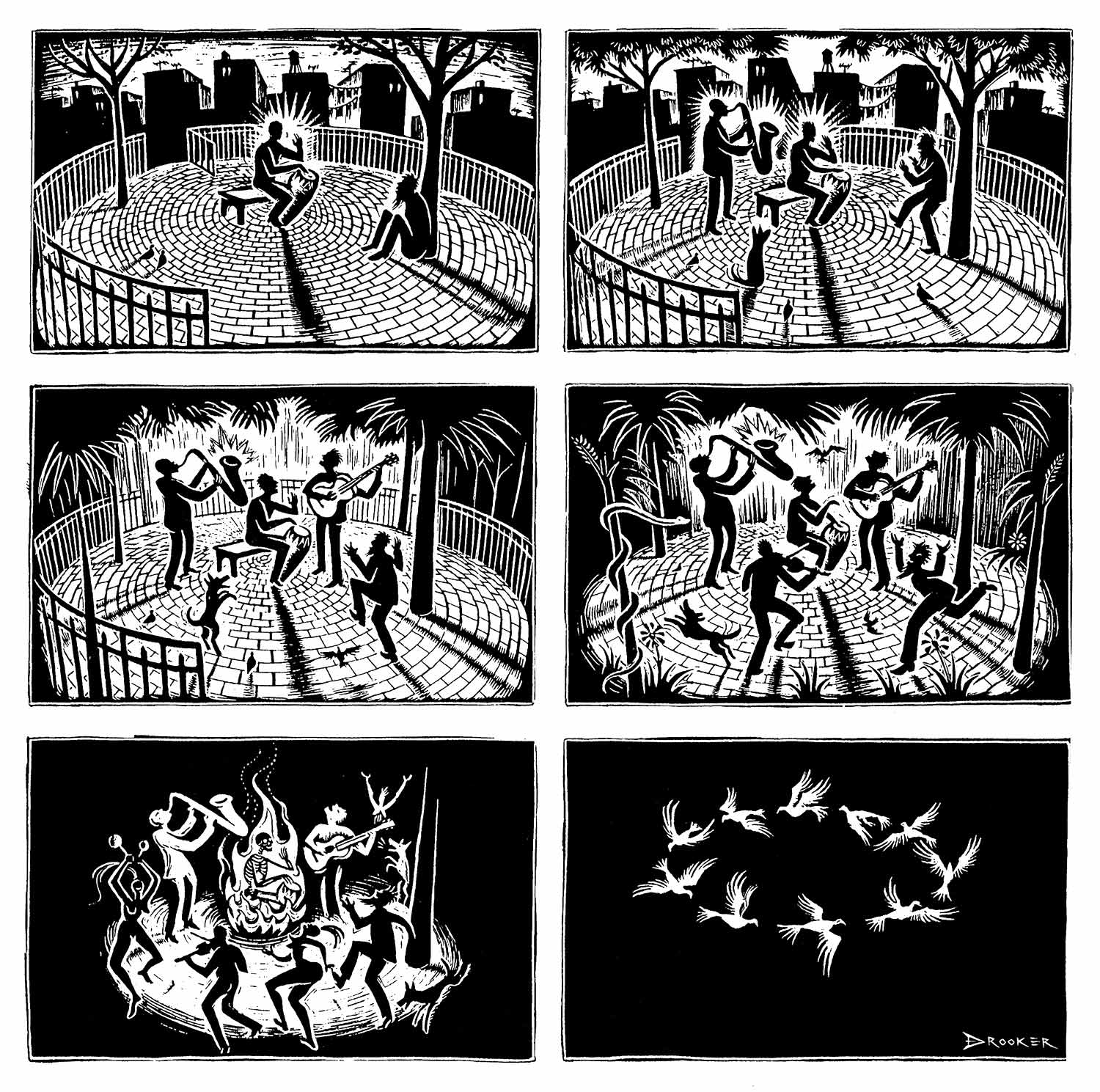

My neighborhood was a place of unrest. I lived right down the block from Tompkins Square Park, where the police attempted to enforce a midnight curfew, in 1988. The park sits in the heart of Lower East Side, a volatile neighborhood with a long, radical history of resistance. So, when a police megaphone ordered everyone out of the park one hot summer night, we all refused to leave. The crowd just stood there, chanting: “Whose fucking park? OUR fucking park!” Then without warning, riot police charged into the crowd on horseback. Screaming and chaos ensued. People reacted by throwing bottles, bricks, and firecrackers at the cops. I took it all personally. This was the park I’d grown up in . . . my playground as a child. I’d never seen this level of violence firsthand—I saw the police just cracking people’s skulls open and galloping into the crowd—helicopters hovering above tenements—an unforgettable, apocalyptic scene. I saw my friends and neighbors fighting against the helmeted police—rebelling against the landlords . . . and it was inspiring as hell. Oh, it was picturesque indeed: nocturnal hordes of uniformed men on horseback, swinging shiny batons. I immediately began working on my next street poster, “Police Riot,” which was wheat-pasted on lampposts and walls throughout the neighborhood. Later I used this image in Flood!’s riot sequence. Ultimately, the band Rage Against the Machine used it as a CD cover.

Were many of your images originally created as street posters?

Oh yes—through the years, I produced countless posters on a range of local issues—usually as a response to some recent occurrence. For instance, the giant woman staring down rows of armored police was inspired by an actual incident. The police arrived with an armored tank to evict squatters from 13th Street and Avenue B—you can’t make this shit up. It happened right across the street from where I grew up, and most of the squatters were friends of mine.

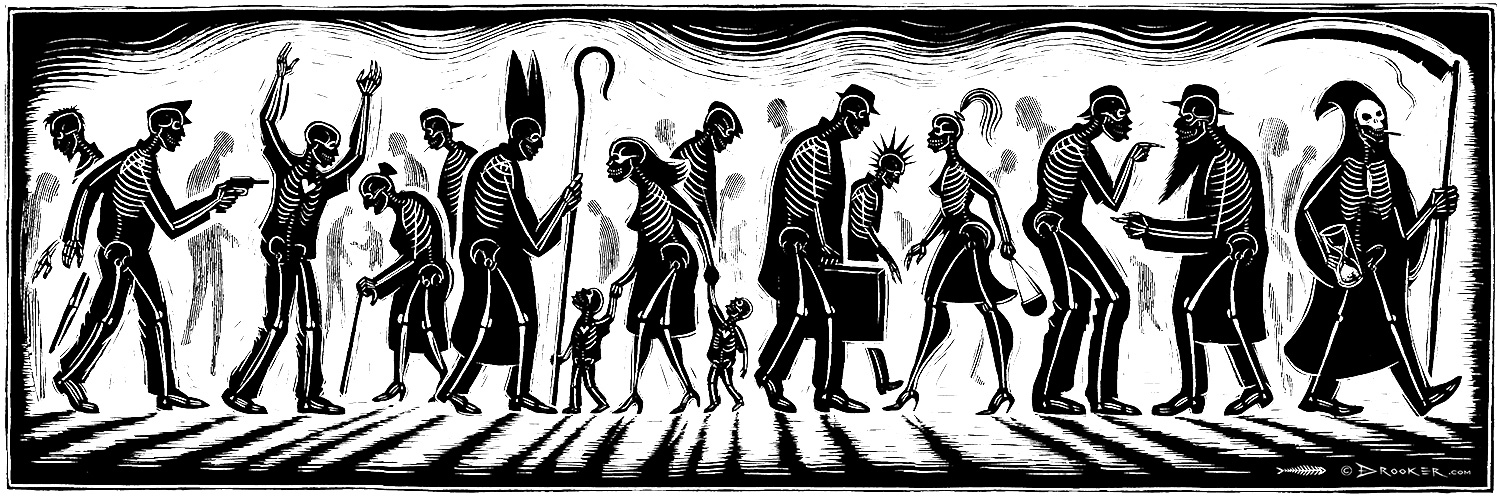

Before we close out, I wanted to ask: The recurring use of skeletons in your work reminds me of Posada. I don’t know whether that’s where you drew it from, but I’m curious when that popped into your work as a motif.

As a teenager, I often drew people as translucent, with their bones exposed. I continued to use this x-ray motif in a series of drawings and clay sculptures I produced at Cooper Union. I then learned that much indigenous art—African, Australian, and Native American—used this x-ray motif. Anthropologists actually refer to it as the “X-Ray Style.” And, yes, I’ve been influenced by Posada, the nineteenth century Mexican engraver who created all those “calaveras” from the Day of the Dead Festival; all those laughing skulls and skeletons dancing around. The Dance Macabre has a long tradition in German art as well. I’ll often use the x-ray motif to suggest a feeling of vulnerability . . . and impermanence. Born out of darkness, we walk around for a few short years, experience the pleasures of the flesh, and soon . . . we’re bones. The hard bones of reality. Check out Paleolithic cave art, from 30,000 BC, and you’ll find that we were making x-ray art back then. Now we have cameras to photograph reality . . . but these machines capture only outer appearances. So, it’s the artist’s job—or poet’s job—to penetrate the outer layers, to reach an inner truth. Truth can be very beautiful. Perhaps truth and beauty are ultimately the same thing . . . I don’t know. What do I know about truth or beauty? I’m just scratching here . . . trying to scratch out a living.