By David Ensminger

Pop Matters

July 29, 2011

One cannot saunter through a bookstore today without stumbling across a punk rock memoir, biography, or oral history. From San Francisco to Detroit, from the Replacements to Darby Crash, the scenes have been endlessly dissected and prodded, with earnest fervor and entrenched nostalgia. For true believers, though, punk rock means much more than a fetish for product.

To them, punk is a constructive tale about stirring culture from below, being pro-active, and doing things: skateboarding, setting up shows in DIY halls, participating in late-night copy store binges printing fanzines or flyers, and making a cassette tape mix with homemade art to be traded with another zealous fan. Heavy metal and hip hop instilled and inspired their own cultural ripples, but punk rock still seems to meld the world of collectors who memorize memorabilia and the world of politics and alienation, in which left-wingers and libertarians often share paranoia and points-of-view.

Black Flag is very personal to me, not because my tame parents raised me anywhere near Hermosa or Redondo Beach, California in 1978. In fact, I was a skinny shy boy, miles south of the Wisconsin border, west of Chicago, ear pressed to Cheap Trick on the jukebox. I dropped nickels into the clunky machine, and at home scooted around my basement, miming Rolling Stones songs, too. I was the kid brother of punk rock, the self-possessed one who played Civil War for hours on end in the backyard and created a boy cave in a cupboard, where I stuffed games and food and told people to leave me alone.

My brother was ten years older. Gay, but not “out,” he graduated in 1980 from a high school built by prison architects, then left for Chicago’s dirty streets and art school. He came back to our sleepy suburb with peroxide-striped hair, a drugged attitude, handfuls of 45 records and fanzines, and breathless stories of seeing Black Flag, with Dez Cadena. The band tore a hole through the somewhat stilted music scene of the Windy City, where groups like power pop Pezband ruled the late ‘70s. To him, Black Flag were avant-garde; to me, they were a blistering earache.

Six years later, in a darkened hull of a cellar club in Rockford, I too saw Black Flag. Donning a yellow Circle Jerks shirt and a fuzzy upper lip, I awaited the buzzsaw, off-kilter power chords and frenetic, rasping Henry Rollins. Instead, I endured an endless barrage of molten, jazz-noise-metal riffage from a band that clearly disdained the charade that punk rock had become.

Still, when I exited the club with a damaged left ear lobe (I was dumb enough to stand in front of their PA stacks, feet away from guitarist Greg Ginn) cops lined the streets with smirks and paddy wagons, taunting passers-by. They acted as if ‘80s-style Los Angeles riots were a potential threat in this rust belt city.

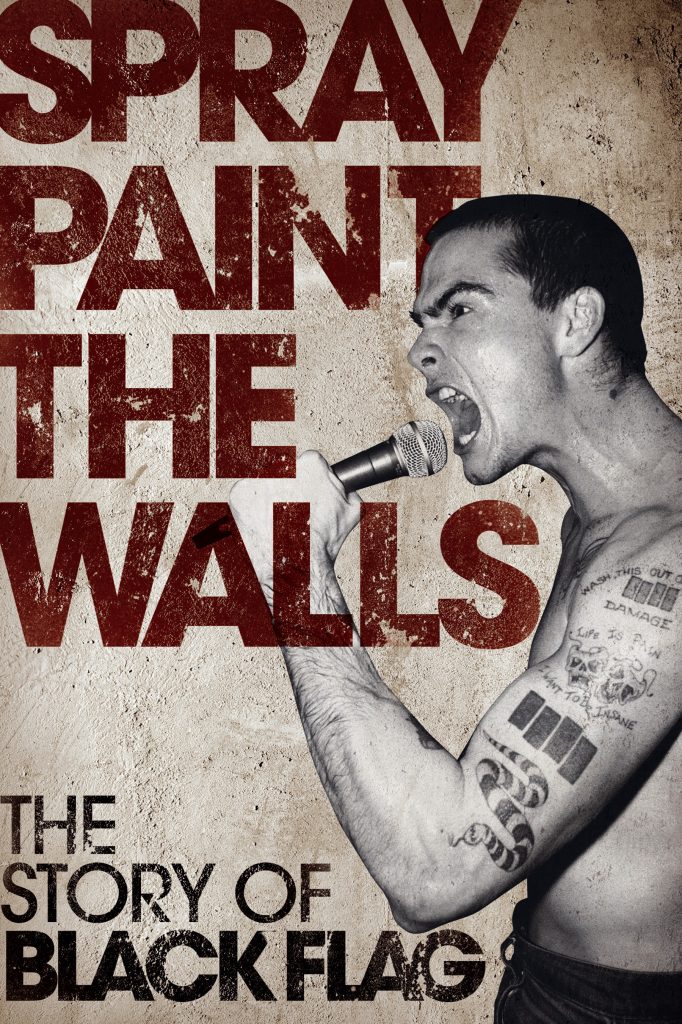

Luckily, Stevie Chick chronicles Black Flag from both ends, mapping how they careened from menacing, berserk, and beachcore outsiders to grizzly hardcore icons to bizarre, and sometimes boring, post-hardcore pioneers that chewed through miles, tours, members, and songs. In doing so, they produced an unstable hybrid between the jugular-busting prowl of the Sex Pistols on speed to King Crimson style sonic mapping. Chick sketches a journalistic portrait imbued with high energy: fervent, toughened, and coiled sentences meld Walt Whitman’s sense of the body electric with Lester Bangs’s maverick verbiage. Plus, he exhibits a new school appreciation for keeping cultural context intact.

Many people will bemoan what’s immediately missing—the voices of Gregg Ginn and Henry Rollins, above all. Instead, Chick delivers from deep slanted angles, using the input of early singer Keith Morris (of famed Circle Jerks and Off!) and bass player Kira Roessler. She first paved her way with bands like Sexsick and Twisted Roots, became the pounding, hand-aching backbone of Black Flag, and later ended up Mike Watt’s (Minutemen, Iggy and the Stooges) short-lived marital mate but long-term companion in art-infused Dos.

In addition, Chick taps penetrating narratives from SST (the label jumpstarted by Greg Ginn) compadres like Mugger (Overkill, Nig-Heist), who now operates a record label out of Oregon, and Tom Troccoli (Tom Troccoli’s Dog). They prove to be earthy and legitimate witnesses: these are the people who hauled the amps, smoked the pot, dropped the acid, berated the audience, and logged the tours with rough aplomb and self-styled anarchy.

In this outing, Chuck Dukowski is the previously overlooked member lionized at length. Gregg Ginn might have been the determined Machiavellian intellectual, and Henry Rollins the enfant terrible turned rock icon and street poet, but Dukowski is the manic player and media savvy provocateur. He understood that politics is not about Truth but a struggle over truths, especially in regards to youth and power in the ‘70s and early ‘80s, in the leftover haze of hippiedom.

As his interviews with local TV news reporters and documentaries like Urban Struggle (chronicling the club The Cuckoo’s Nest) attest, Dukowski’s street politics invoked contested physical space, access to media, and autonomy for youth. Politics meant debating who could control venues. Teeming with images culled from Raymond Pettibon’s art, Black Flag’s mass-produced handbills became insurgent folk art that promoted shows, threatened uptight civil society, and created an informal network of fans—a teenage wheat paste army of Black Flag.

Politics was not first and foremost about ballot boxes, Dukowski knew, it was about being a conduit for the resentful, the ignored, and the inflamed kids in the neighborhoods teeming with boredom.

Most of the text is aimed at the pre-My War years, before Black Flag mutated beyond recognition, according to many fans. In doing so, Chick offers a depthy read, painting a long-overdue portrait that also includes bands like The Last and Descendents. Though the narrative gets more scant as Black Flag’s career unfolds in Reagan’s second term, Chick still packs quite an analysis of records like Slip it In.

He chooses not to ignore or gloss over the seismic sexism unleashed both on the road by Nig-Heist and on tracks by Black Flag as well. Plus, his hyperbolic, breathless prose fits the grooves of a band interested more in Charles Manson, Black Sabbath, and Grateful Dead than GBH and English Dogs.

For a plunge into SST lore, this is the book to grab for summer’s enervating heat. Don’t expect newfound testimonies that will upset the Black Flag brand, but do expect a fascinating and eventful journey into the heart of damaged territory.