by Laura Tanna

Jamaica Gleaner

August 26, 2012

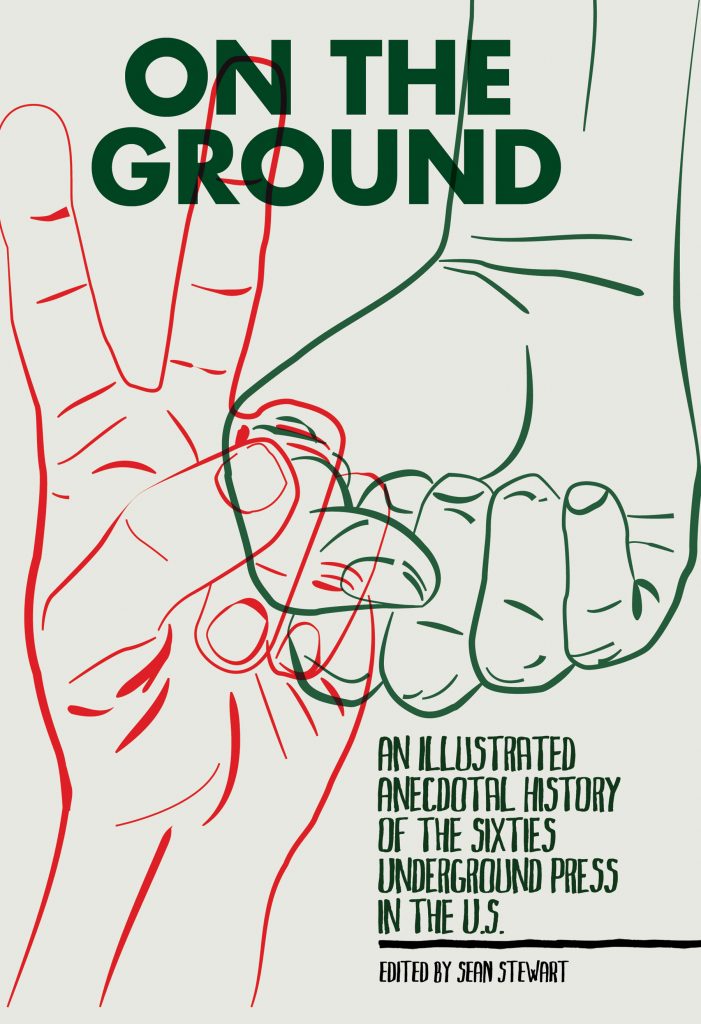

A Jamaican’s take on the United States at one of its most stimulating periods of political and social growth

This

book, edited by a scion of the Jamaican Kennedy clan—though he prefers

to be acknowledged on his individual credits—was given to me by a media

colleague who knew that I had graduated from the University of

California at Berkeley in 1969, hotbed of student radicalism in the

’60s, after meeting my future husband upon my arrival there in 1965.

Yes,

can you imagine Dhiru Tanna giving a rousing speech on behalf of the

movement against colonialism on the steps of Sproul Hall? But he did,

and we both took the student movement at Berkeley in our strides as part

of our education. We were global before most people knew what was

entailed in that term.

But what my colleague here didn’t know was

that although I started high school in a segregated town in Indiana,

and then became the first American to ever attend the Shia Imami

Ismailia Secondary School in Kampala, Uganda—a Muslim school for those

of you who aren’t up on your Islamic terminology—I also ended my

secondary school education at Friends Seminary—a private Quaker New York

school where most of the students were Jewish or Episcopalian – while

living in Greenwich Village, so that between Berkeley and the Village,

while helping to edit The Journal of New African Literature and the Arts

(JONALA) while in California.

I can probably appreciate Sean

Stewart’s book better than most people in Jamaica or, for that matter,

in the United States of America. Now, normally, I take a very low

profile, usually eliminating myself from interviews to the extent that

most people don’t even realise those which I have done. But in this

case, I want you to know that I am qualified to tell you that this is a

brilliant book.

One of my Jamaican friends in Miami picked it up

and was mesmerised by the posters and magazine covers from the ’60s’

underground press reproduced in On The Ground.

Unfortunately,

for copyright reasons, we can’t reproduce them for you here, but what

Sean has done is to research the publications which were instrumental in

fomenting the fight for human rights, whether they be against the war

in Vietnam, or discrimination against people of colour, or

discrimination against women or those whose sexual orientation is not

that of most others. The underground press started on the former, but

over the years, showed the way towards the liberation of all others.

Now

Sean Stewart, born and raised in Kingston, then having migrated to

North America, appreciated that in these small local presses, in some

cases no more than mimeographed handouts on street corners, herein lay

what press freedom and social progress is all about.

GOOD PERSPECTIVE

His

editing takes a little time to grow on the reader, but it is useful. He

selects excerpts from interviews with, or writings by, various

underground editors or authors—whether they be Jewish high-school

students, middle-class Midwesterners or members of the Black Panther

movement—and isolates them into subjects within chapters.

After a

while, you get to know the different personalities and move with the

times and the themes that Stewart has selected. In so doing, he creates a

superb history of America at one of its most stimulating periods of

political and social growth. Anybody wanting to understand what modern

America is all about should read this volume.

It’s not always

easy. Some of it is disconcerting, discombobulating for those not

familiar with this decade, but persevere. You will start to grasp what

motivates the baby-boomer generation that now holds sway in positions of

power, or that motivates those who resent the potential liberalism

represented by the ideas put forth in the underground press.

Paul

Buhle in his preface proclaims: “We changed journalism, battled

repressive laws” and they had fun in the process. Jamaicans should

especially appreciate this book because it speaks to individuality,

neither conformist nor non-conformist. It deals with the sacredness of

human life, examines the moral courage of direct action during the civil

rights movement, and illustrates how journalism became a lifestyle of

total immersion, both political and cultural.

GREAT READ

I

have pages of quotations of relevance from this volume, too many to

share with you here. For example, this quote from Ben Morea, of Black

Mask, The Family, which illustrates the power of music, something

Jamaicans understand, and these were free concerts.

“There was a

certain cultural antagonism between the ghetto-dweller and the youth,

the hippie. They didn’t quite have the same background, so our role was

always to try and ease that tension . . . We’d have black bands or steel

drum bands, rock bands, and Latin bands all playing together so the

audience would be all three. I mean that was our goal, it was conscious.

We would try to bring together art and politics or ghetto and hippie—we

were always trying to bridge gaps.”

On The Ground,

available on Amazon.com, is probably going to be difficult for you to

find in a local bookstore, but look for it, read it, and appreciate how

Jamaicans of all backgrounds contribute to understanding our global

culture and how it has evolved.