By Lolita Lark

RalphMag

February 2012

If you had the misfortune to live through the Eisenhower years, you will know how stifling, tedious, uneventful, yawn-inducing, stultifying and ultimately soul-killing those times were. We all knew that a small clan in Washington along with an even smaller one in Moscow held our lives in their hands as their hands inched towards the red buttons marked ICBM.

They threatened each other but not as much as they threatened us—for the button-pushers all had bunkers where they would ride out the ruination of the world. With that knowledge—you and me fried, them bunkered down underground—they were scaring the rest of us to death. They flitted from crisis to crisis, getting closer to the moment when most of the rest of us would be no more.

Those who didn’t live through it will never know how bleak these times were. We were all sitting on death row and the executioners babbled on, obviously not caring what we thought or wanted. All our lives hung by a threat (I meant to write “thread,” but the other will do as well). The continuing close calls (Berlin, Hungary, Suez, Cuba, Quemoy, Matsu) made the rest of us sure that we were going to be incinerated by a blaze initiated by a bunch of dolts. And every time we protested, we were accused of siding with the enemy.

I think most of us reacted as people do when they are faced with their own immanent death. Those floating at the edge—capital punishment, cancer, heart disease, no matter how brave, pious and accepting—seem to turn inwards and distant, what Keats defined as ending up in the place

1. “Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;

2. Where but to think is to be full of sorrow.”

§ § §

And yet in the midst of this madness, a ray of light burst forth. First there was Paul Krassner’s Realist. Within a short time, Max Scheer’s Berkeley Barb, Art Kunkin’s Los Angeles Free Press, John Wilcock’s East Village Other, the Oracle in San Francisco (one of the most fetching, with its delicate tracery) . . . along with others at East Michigan State University and the University of Texas.

Then suddenly there were hundreds of tabloids, filled with a sane madness, all made possible by “photo-offset.” So simple, so obvious, so cheap. All you had to do was to stick stuff on a piece of cardboard (typeset, rub-on letters for headlines, halftones) and then you’d take it to the printer, and he would shoot it, and you’d say “we want 5,000 copies,” and they would do it on newsprint, cheap rough paper, and suddenly, as Thorne Dreyer writes, “It was amazing because it started out being five or six underground newspapers and eventually there were hundreds all over the world.”

On the Ground consists of interviews with a couple of dozen of those who were there at the beginning: Krassner, Kunkin, Scheer, Shero, and—trying to tie them all together—the Liberation News Service. It’s a great deal of fun to read these memoirs, brings back memories of ratty offices with people everywhere, doing all sorts of weird stuff. For example, Judy Gumbo Albert worked for the Barb, in their sex-ad department (and their sex ads were a howl): “I always knew when one of my favorite clients was walking down the street on his way into the Barb office because I recognized the loud clanking from the chains he wore.” He was, she tells us, “very sweet and polite” and he would write his ad, “Seeking young man for western games.”

1. I was a naïve young woman from Canada; this job really opened me up to, and made me appreciate the diversity of human sexuality.

§ § §

One of the best interviews here is with Harvey Wasserman. He helped start LNS and here he nails down for all of us the ethos of the times. It was about building a community, about suddenly finding others who felt that America was on the wrong track . . . feeling that we had a chance to get things back on course again.

In the process, we built communities, communities of like-minded people, who we could hang out with, get stoned with, work with: “You start off with a small core and people are on each other’s wavelength, personally and politically, you think the same way . . . and there is no decision-making problem. It’s a family situation, really.”

1. We never had editorial meetings. Anybody in our little group who wanted to put out an article put it out. We all loved each other’s stuff . . . we really were just all on the same page.

And then, sigh, inevitably, “The group in New York wanted to have editorial meetings to decide what was going to go in the news service. Our feeling was: we’re not a newspaper, we’re a news service, we’re putting stuff out there and if the editors want to run it that’s up to them.”

1. It was a magical time for us. And that word “magic” was used because somehow everything was impossible, all the situations we confronted were impossible, and somehow we got through them.

And then “they wanted to throw us out . . . We started having these meetings to work things out. It’s like a marriage, when you start having meetings you know you’re in trouble.”

§ § §

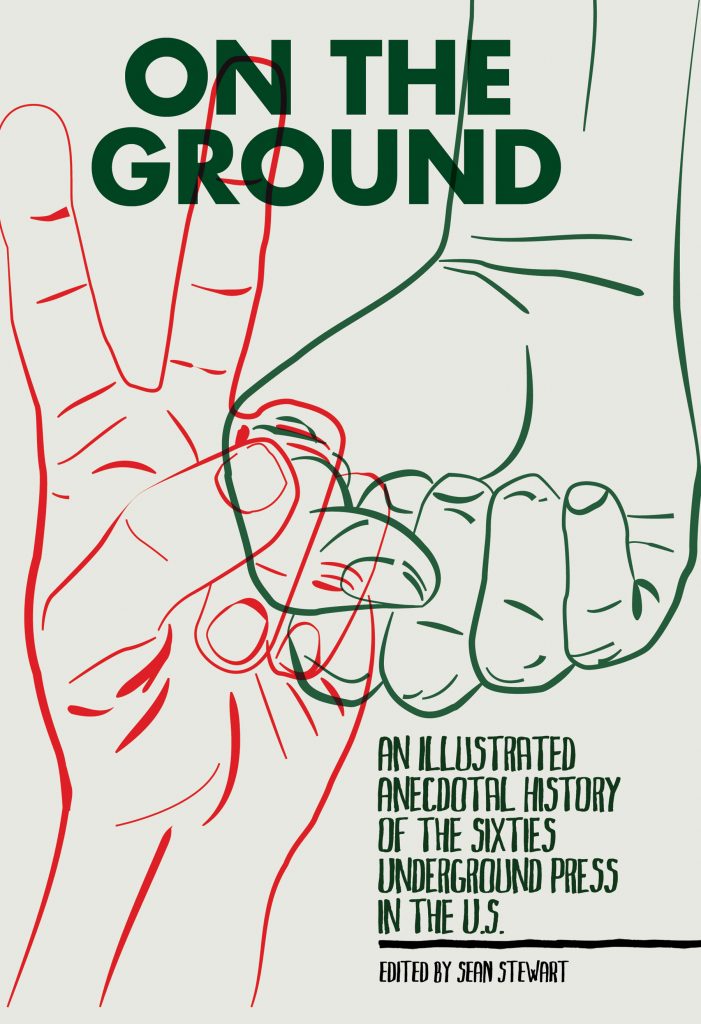

If you are an old underground fan like I am, the pictures here will knock you out. Full page spreads from the Barb or the Seed or Rat . . . and the drawings: “The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers”—I actually had friends from back then that looked like the three of them. Oh, the cartoons. My god, there are a couple here by Crumb that in the not-so-stoned twenty-first century could get you locked up in the gray-bar hotel. We’re surprised that PM had the guts to publish them. And as I am writing this I am thinking: What has happened to us now? What are we so afraid of now?