By Stewart Dean Ebersole II

AMP Magazine

November 10, 2011

They were the pioneers of American hardcore, forming in California in 1978 and splitting up eight years later leaving behind them a trail of blood, carnage and brutal, brilliant music. Throughout the years they fought with the police, record industry and their own fans. This is the band’s story from the inside, drawing upon exclusive interviews with the group’s members, their contemporaries and the groups who were inspired by them. It’s also the story of American hardcore music, from the perspective of the group who did more to take the sound to the clubs, squats and community halls in American than any other. In this interview, Stewart Dean Ebersole II, author of Barred For Life (forthcoming) speaks with Stevie Chick about the book “Spray Paint The Walls: The Story of Black Flag.” Living through the early 1980s, for many young people, was a total downer. Kids growing up in almost any age may have made the same claim for “their” era, but the 1980s were troubling beyond most. The 1970s—remembered here in America mostly for a long-lasting economic recession, persistent troubles in the Middle East, oil shortages, cocaine abuse, disco music, leisure suits, and the like—gave way to a utopian conservative movement at the hands of one Ronald Wilson Reagan, America’s fortieth president, in 1980.

If it is possible to view the 1970s in any positive sort of light, the conservatism of the 1980s was just so damned oppressive. Under the divine guid- ance of President Reagan, America super-escalated the Cold War with Russia, shipped American jobs far offshore, cut taxes for the rich, and basically kept the citizens in fear by proclaiming that the rest of the known world was dead set on destroying America simply because they resented our freedoms. The rest of the world didn’t like the United States, they feared the United States; and there was a difference. Like back in high school, you might not have liked the bully but you were nice to him so that he would be less likely to kick your sorry little ass, right? Well, this was the same shit on but on a worldwide scale.

Punk rock arrived shortly before the Reagan presidency but gathered its swagger under it. If punk was a loosely affiliated music scene beforehand, Reagan’s ultraconservative machine gave punk rock bands a huge target at which to lob insults, threats, and liberal responses to conservative dog- matism. If things seemed to be picture perfect to those harvesting from the excesses of the fear brokered by the Reagan regime, it was anything but perfect to the rest of the America—the one that seemed to be getting dismantled by the hand that was so cleverly hidden behind the face of social conservatism. And to this condition I believe punk rock spoke with great force and with a truth-to-spare. If mainstream liberals were sent run- ning to hide from the light of a conservative change of tides, punks were the holdouts, the rebels, and the group whose spirit was ignited and not extinguished when Reagan’s saints came marching in.

Bands formed, if for no other reason, than to combat this rapidly changing tide. While the “entitled” worldwide launched criticism at punk rock for merely existing, punk rock was undaunted by anything but by its own lack of directional unity. Punk-rock fury took on everything from Reagan’s secret wars, to the unfortunate implementation of Reaganomics, to the throngs of Yuppies that now took up social residence where the drug- addled disco-phytes of the 1970s had vacated years earlier. Punk rock, then, represented a last stand of liberal ideals in a world that had suddenly decided that freedom to voice one’s opinion should be at the very least hindered, if not fully eliminated from the international forum.

Punk rock took on the entire world for a handful of crazy years in the early 1980s, and gave voice to a group of people who, for all intent, were being silenced by the tenets of worldwide conservatism. If the growing sector of poor and dis- possessed around the world were not going to be heard of their own will, well, punk rock would speak for them. Bands that formed in the mid-to-late 1970s, in response to the stale and overly indulgent rock of the era, found a new energy in the age of conservatism, and so when we culture-starved punk rockers collectively jumped on board, some bands—while already a few years old—seemed both brand new and totally original to us. In some respects the first wave of American hardcore bands were perfect, since they were essentially untainted by the music industry that one day would consume them.

Bands like the Bad Brains, Dead Kennedys, Minor Threat, Agnostic Front, Articles of Faith, and so many others became the instant voice of pissed-off punks.

These bands were on fire. Not since the first generation of hippies of the early 1960s had there been an amazing opportunity for music to take on the establishment, and it seemed like punk rock bands were going for broke and not looking back. Punk rock, at least in the early stages of its existence, was a hail of bullets fired directly at the establishment, and punk rockers were a grotesque and disfigured infantry with nothing at all to lose.

Formed in 1976 in the small surfing town of Hermosa Beach, California, the band Black Flag seemed to mature slowly (though surely) through the end of the 1970s mostly due to rapid membership changes. Led by an eccentric guitarist named Greg Ginn, Black Flag gelled around a caustic mixture of aggressive music and interactive stage presence that, to those listening back across their discography, had no precedent in the music world. Sure, there were hints of the Sex Pistol in the mix, but Black Flag’s early sound, like so many of the bands of that era of American hardcore, came out of the clear blue sky and ready to take on all comers. While most of the popular bands of the time took aim at specific historical targets, Black Flag confronted deeper, less immediately tangible targets.

Sure, there were songs about the police and the government, but Black Flag as a whole was serving up fodder for contemplation. It wasn’t solely about “the police” or “the gov- ernment,” but was about the abuse of power of the establishment and how it translates to individuals that stand in its way. It was just deeper, albeit not too much deeper, than random attacks at Reagan, Thatcher, or other easily identifiable human targets. And with the biting cynicism of its many venomous singers, the musical assault made Black Flag a band to take personally, because they, for all intent, were you. They weren’t singing to you, they were relating with you. “Depression,” “Rise Above,” “Police Story,” “American Waste,” and so many other memorable songs just completely captured the spirit of anger, if not hatred, for a system that was trying to silence dissenting opinions, and Black Flag entered into the spotlight for simply offering rational responses to a world gone totally mad, and not vice versa.

And then something very strange happened . . .

Ten years, four singers, three bass players, and drummers too numerous to count, later, Black Flag was gone. For quite a while after their epic My War release, it was hard to classify Black Flag as punk rock at all, and so for quite a while after their demise punk rockers turned their back on the band that best spoke to their generation just a few years earlier.

Many years later, however, after the smoke had cleared up just a little bit, Black Flag crept back into the ever-evolving punk rock dialogue. Slowly at first, after being mentioned by Kurt Cobain as a principal influence on his band, Nirvana, and then picking up masses of momentum in the early 2000’s. Black Flag eventually was given credit for all of their amazing talents, including even their ability to say “fuck you” to a fan base that had come to expect certain things from a band that was dead set on evolving away from “the old stuff,” and offering new musical ideas for a movement that had gone more than a bit stale.

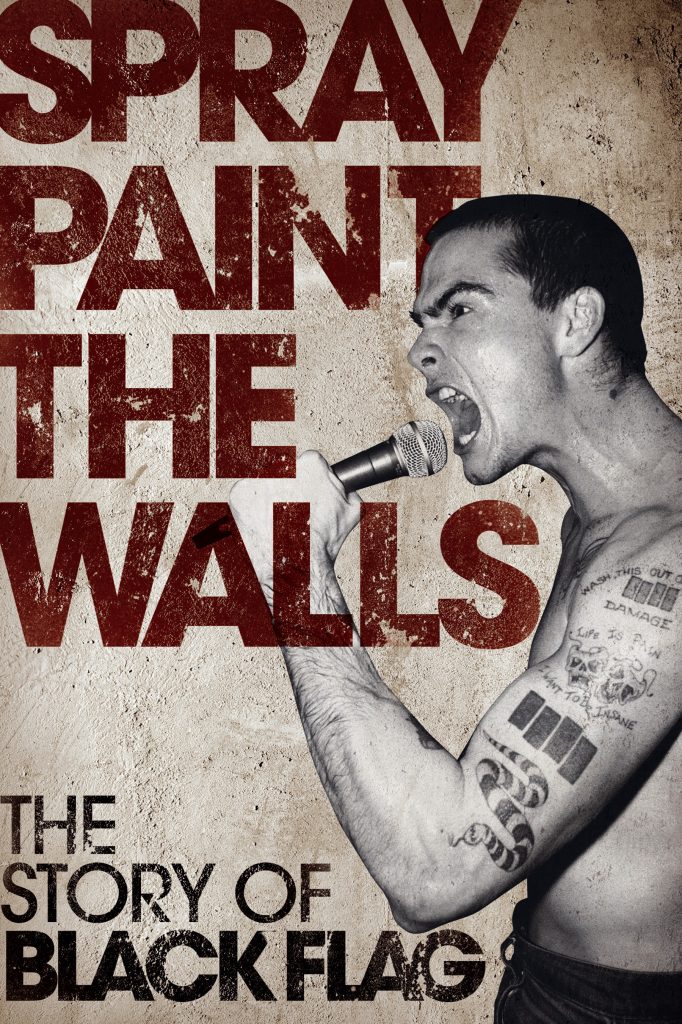

Today, their logo, The Bars, is probably the most universally identifiable punk rock icon, while Black Flag (at least the idealized Black Flag) has become the band most associated with the crazy world of American hardcore music from the early 1980s. And while many of its members are still somewhat traumatized by their association with being part of this epic musical unit, some are talking. And while these voices are talking some outside ears are listening, taking notes, and trying to make sense of Black Flag’s tumultuous existence, curious evolutionary path, and contentious breakup. Among those early note-takers was Stevie Chick, a British music writer with a lust for American pop culture and a deep apprecia- tion for all things Black Flag.

I read Chick’s Spray Paint the Walls while doing research for my own Black Flag-related book entitled Barred for Life. Like me, Chick found the usual suspects ready to talk about their association with Black Flag, and a list of others fully unavailable for comment. Having disintegrated unceremoniously over twenty-five years ago, one might think that the individuals peopling the various Black Flag lineups, road crew, and friendship circle would have come to terms with their “punk rock legend” status, but many haven’t. As when the band was actively moving forward, the key players in Black Flag still fan flames and discontent, and that may be one of the things that keep us so interested in the band and its collective history.

An unlikely candidate to take on the twists and turns of America’s most leg- endary hardcore band, Chick covered the territory as only an investigative journalist could. Weaving fact, hearsay, pure fiction, and idealized instances, Spray Paint the Walls stands out as the definitive documentary on this groundbreaking band’s lifecycle and numerous manifestations.

Covering a wide spectrum of individuals who were either in Black Flag, supported Black Flag, or were close to Black Flag at any point along their ten-year timeline, many of the band’s seemingly random direc- tional changes become immediately understandable in a historical context to those who want to know more about the inner workings of this peerless musical unit.

Spray Paint the Walls is an inspiring effort. Taking a mountain of complicated interviews with complex individuals and somehow turning them into readable narrative is one thing, but I was quite surprised just how easy Chick’s volume is to read and understand. Making the crazy story of Black Flag into an easy-to-read book, no matter how it is couched, is a monumental, and well-received (by me) success for better understanding this most important component of our generally underrepresented subcultural history.

After reading the book cover-to-cover, I am not all that sad that Ginn and Rollins declined interviews. In my opinion, their friends tell the story as it needs to be told, which is logical, straight-forward, slanted positively, and at times more than a bit idealistic. Plus, the read is anger and rivalry-free, which steers away from persisting inner-band dramas.

But like anything, after reading Spray Paint the Walls I had more questions than questions answered about this mysterious band and its mysterious cast, and so I decided to check in with Mr. Chick and score some needed clarity. Using the convenience of modern social networking channels, Chick graciously supplied answers to my questions concerning his experiences researching and writing his book.

Stewart Ebersole: Stevie, tell me a little bit about yourself, your pedigree as a journalist and documentary writer, and how you ended up dealing with aspects of American hardcore punk music.

Stevie Chick: I’ve been writing about music professionally for thirteen or so years now. I started out publishing my own zine before freelancing for Melody Maker, both of which led to stints writing for larger music and culture magazines. Now I mainly write for MOJO and The Guardian, along with TheQuietus.com.

In 2001 I helped Everett True and Steve Gullick start up Careless Talk Costs Lives, a high-quality zine covering underground music, following which Steve and I started up our own zine called Loose Lips Sink Ships. Spray Paint the Walls is the second of my three books to date; I also wrote 2007’s Psychic Confusion: The Sonic Youth Story and, in 2010, Ninja Tune: 20 Years Of Beats ’n’ Pieces.

Over those thirteen years, I’ve been lucky enough to interview godhead heroes like George Clinton, Ian MacKaye, and Sonic Youth, travel Brazil with the White Stripes and wander late night Amsterdam with The Mars Volta, hide out from angry Hard Rock Café bouncers in Austin with The Icarus Line after their guitarist Aaron North liberated and attempted to play Stevie Ray Vaughn’s framed guitar, and write about the music that I love, that I think is truly important, and life-changing.

It’s a blast, what can I tell you? I’m broke as fuck but my life is rich, or some shit like that.

SE: Okay, well do you at least find any irony in that fact that you, a British journalist, have just written the definitive biography on Black Flag, America’s most infamous hardcore punk rock band?

SC: Not massively . . . I’m such a dedicated Yankophile I don’t think my “Englishness” was really an issue. It’s not all tea and scones and the Kinks over here, you know, and I’ve always had an abiding fascination for American culture, and particularly American pop culture, and specifically American music. To be honest, it’s surprising to me that no American writers had really tried to tell the Black Flag story in such depth before, let alone me doing so from here in the UK. I did go to California for an early research trip where I visited a bunch of the locations that are mentioned in the book, and interviewed people like Keith Morris, Kira Roessler, Mike Watt, and Dave Markey on their home turf.

SE: So what specifically got you interested in Black Flag? They were only one great band among many in the American hardcore scene . . . no?

SC: I was sixteen when [Nirvana’s] Nevermind hit, and that record dragged me down a rabbit hole and introduced me to a world of underground American music that spoke so powerfully, so directly to me. It was shortly after that, that I discovered Black Flag, and again an album like Damaged is of a universal na- ture that transcends nationality: I am young, I am fucked up, I am upset about it, and I want to express this fucked-upness before it destroys me. That spoke to me, and the roar of Chuck Dukowski’s bass, the scree of Greg Ginn’s guitar, the bellicose bark of Rollins all spoke to me too.

SE: So what made you decide to attack a topic that no American journalist, or any writer for that matter, has ever really had the guts to do, and complete it without a seeming bump in the road?

SC: I was thinking about that today . . . Basically, the book began with a meeting with my editor. I’d just written a Sonic Youth biography for him the year before, and we were discussing possible subjects for my second book. He mentioned that there’d been interest in a book on Black Flag, and the moment he said it, it seemed like a great project to really sink my teeth into.

Like I said, I’d been hugely in- spired by hardcore as a kid, self-starters like Ian MacKaye and Greg Ginn, who went ahead and, when no one else would, built the touring network that underground bands still follow to this very day. I thought Black Flag were glo- rious, righteous, and that it would be an uplifting and inspiring tale. Again, I had no idea how complex the tale would prove to be, and to tell.

You know, even though I loved their music, I wasn’t aware when I took on the project how fractured the relationships were between some of the members of the group. I’d read Get in the Van as a teenager and, sure, I remembered the enmity between Rollins and his bandmates towards the end; but fuck it, Rollins expressed enmity towards everything and every- one at different points in that book. And sure, the way the group ended, as recounted in Get in the Van, seemed pretty bleak and odd.

I guess I just assumed that, over the years, the members had gotten over their old intra-band beefs enough to be able to celebrate their band without rancor. What I’m saying is, even though I was aware of the weirdness that surrounded the “reunion” in 2003, I had no idea how difficult this book would be to assemble. I just knew that it was a great story and, again, I didn’t understand why it hadn’t been told before.

SE: Tell me about your process, especially in how you got former Black Flag people (and their entourage) to talk so openly about the band?

SC: The internet was my friend, and I tracked down various interview subjects via their websites, their Facebook and MySpace pages, via other interviewees, and some I’d already interviewed previously and had an ongoing relationship with.

SE: Did you get any “no” answers? If you did, can you tell me who, and why they declined?

SC: I didn’t get any outright “no” answers, which wasn’t the case with my Sonic Youth book: on that project, one unnamed possible subject turned me down cold, saying they’d be interested in talking to me when I get around to writing a book about them. Mostly, those who didn’t want to be interviewed for the Flag book signaled it by either not replying to my initial email, or by simply dropping off the face of the Earth.

SE: Do you find it at all strange that the chief architect of the band, Greg Ginn, and the most infamous singer, Henry Rollins, are reticent to talk about their experiences some thirty years

after the band has been broken up?

SC: I completely understand Rollins’s decision not to talk. He said it all in Get in the Van, and every time he’s talked about Black Flag in the past—and in a manner that, without fail, glories the efforts of Greg and Chuck and every singer who came before him over his own contribution—it seems to have only provoked more enmity from Greg. I imagine it’s still a very painful subject for him, so while I’m disappointed, deeply so, that I couldn’t talk to him, I do understand why.

I wish Greg would talk more, because I think he’s a fascinating character, a pivotal figure in American rock music and DIY culture, and his perspective on the story would be invaluable. I think he’s quite misunderstood, and I think he achieved amazing things. But again, I understand . . . I think he’s so deep in the music that that’s how he can express and articulate himself. I do wish I could have spoken to him though, of course.

SE: Who were your most revealing interviews, and what things did you learn from these interviews that pushed you to keep on going?

SC: Well, I was especially interested in the roots of the group, and Keith in particular was a great fountain of information about those early days, giving a sense of Hermosa Beach’s vibe. [Hermosa Beach is] a mildly affluent suburb with all that entails, but the Hermosa Beach of the mid-to-late ’70s was a saltier, more bohemian place, with some interesting countercultural figures who helped pave what little ground there was for Black Flag to ferment upon. Learning about how the principals first met, before Greg Ginn was the guitar hero/label mogul we know him as now, back when Keith was just a party-loving ne’er-do-well, was illuminating, and the desire to recreate that scene in as great a detail as I could for the readers really kept me pumped.

The world Black Flag operated within throughout their career seems really unexplored, hermetically sealed off from us, so really being able to explore any of that was a thrill, both as a fan, and as a writer looking for an engrossing story to tell. Capturing the vibe of life within The Church, what it felt like to be caught up in (and accused of provoking) the violence that engulfed hardcore (and which the Flag never seemed able to shake), understanding the impulses that kept the musicians committed to such a painful and, in the short-term at least, unrewarding path, following the evolution of the group and their label and their ultimate dissolution . . . These were my goals, and I was thrilled by the challenge and, as I said, fascinated in the answers I found to my questions about Black Flag, because I was, and remain, a huge fan of the group.

Keith Morris, as I mentioned above, was a hilari- ous and impassioned and lucid interviewee, and seemed every bit as excited about the book as I was, and has remained an encouraging voice.

Chuck Dukowski spoke openly about a story that was still emotionally raw to him, and I appreciate that it wasn’t remotely easy. I hope he thinks his efforts were worth it, because I felt I learned a lot from him.

Ron Reyes was perhaps the biggest coup—he hadn’t spoken to anyone in years before I interviewed him for the book, and he was funny, sweet, honest, and a pleasure to interview. I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to speak to him had Joe Nolte of the Last not put me in touch with him, and talking to Joe was like leafing through the pages of some unpublished encyclopedia of South Bay punk rock, a truly solid and awesome guy.

Joe Carducci was a mensch [a good person that helps others], his books were invaluable sources, and the five hours we spent on the phone were an electrifying way to see in the dawn.

Kira was sharp, forthright, and insightful, and a really awesome person. Mugger was honest to a degree that spared no prisoners. Dave Markey was a key and passionate voice. Mike Watt was, as he always is, just 110 percent punk rock, and I got to talk to him on his home turf, which made this Minutemen-obsessive’s year, let me tell you.

Mark Arm remains the coolest motherfucker in rock. Perhaps the most encouraging voice throughout the interview process was Brendan Mullen, whose contributions to the book were integral to sketching out the reality of the L.A. punk landscape of that era, and who, like Keith, seemed at least as excited as me that this book was going to get written. Brendan didn’t get a chance to read the finished book, but I’m not sure it would’ve gotten finished without his encouragement and his geeing up at key moments of my spirit-flagging exhaustion.

SE: While doing your research for Spray Paint the Walls, did you feel like your thoughts about Black Flag at the beginning were spot-on, or did you meet with more unexpected twists and turns than you could have imagined?

SC: I think that in my head I saw [Black Flag’s] independence, their struggle, in idealized terms; admiring what they achieved, and imagining it could only have been accomplished if all the members were selflessly dedicated to their cause and superhuman in their abilities. The truth is, the people in Black Flag were very human, very vulnerable, very complex.

I remember Joe Carducci talking to me about how they were all under pressure within Black Flag’s world, and that because of the dysfunction they’d all grown up with [as individuals], they probably weren’t best prepared to deal with the pressures in a positive way. So some terrible things happened between the people involved in this struggle. There were successes but there were also frus- trations, and the successes came at such amazing costs in terms of their health, their psyche, and their mental balance.

They were not superhuman dudes who went through all that and were still cozy bros, all laughin’ it off and hoisting frosty mugs to their shared cause. To me, that insight just makes [Black Flag] all the more heroic, makes what they achieved all the more remarkable. I came away with a deeper admiration for the people I interviewed, and also the people I didn’t get to interview, but who were remembered [by those interviewed] in such vivid terms.

SE: From your own standpoint, then, do you think that it is fair to treat the entire evolution of Black Flag as a single issue, or do you think that as a band they were far more complicated than that?

SC: Their evolution is very interesting and very complex, but there’s a strong arc in there.

I’ve spent countless hours pondering all the “what ifs?” Like if they’d recorded a follow-up to Damaged in 1982, if they’d stuck with any one of their singers pre-Henry, if they’d let someone else run SST and they focused on just the band, or if circumstances had been different and they’d been able to exist in a more comfortable manner. The truth is that the cards fell where they fell, and while I know some fans don’t feel the later Black Flag albums, I think they’re very strong releases.

. In tracing their path from brutally primal punk rock to sick, shredded jazz-sludge you get a sense of one of the greatest stories in rock ‘n’ roll. They’re a massively complicated, nuanced, and contradictory band, but that’s what makes them so fascinating.

Stevie Chick’s Spray Paint the Walls: The Story of Black Flag is now available in a U.S. pressing through PM Press for $19.95 and can be ordered at www.pmpress.org.