By Margaret Randall

Policy Futures in Education

2016

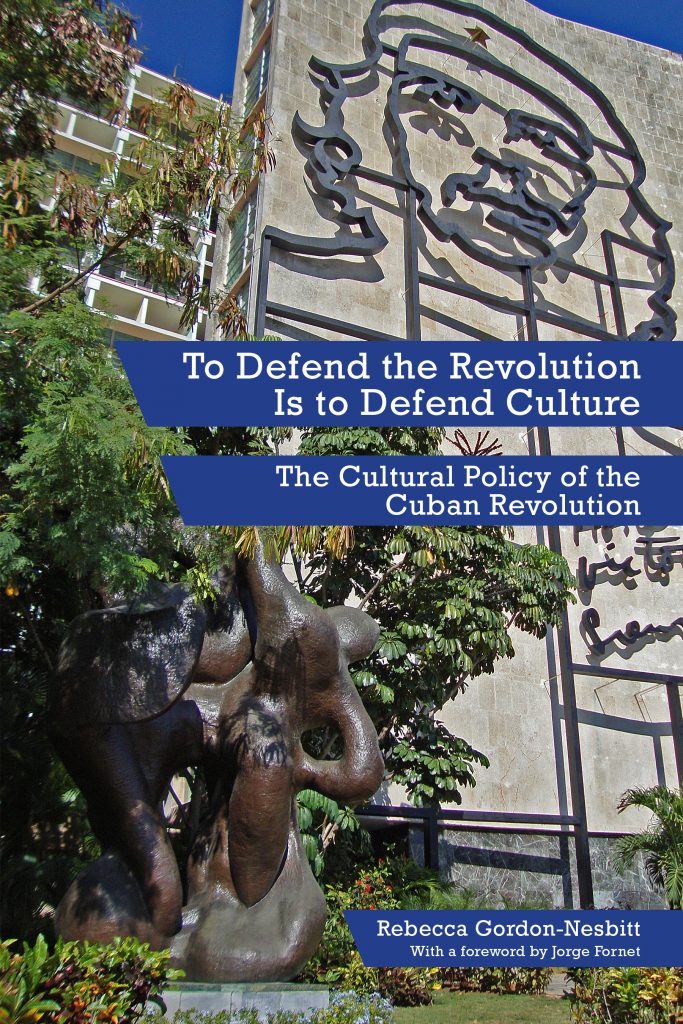

With To Defend the Revolution Is to Defend Culture, Rebecca Gordon-Nesbit gives us a real gift: a roadmap for understanding the ups and downs of the Cuban Revolution’s cultural policy, a subject that has been approached by many on both sides of the political divide, but never before in English with such research, care, and thoughtfulness.

Historically, revolutions have had trouble with culture: how to nurture and promote it, how to make it accessible to masses of people without dumbing it down or reducing it to a fraction of its richness, deciding who must control it and how to exercise that control. Revolutions themselves are cultural phenomena, as well as political, economic, and social. The Cuban Revolution is no exception to these dilemmas, and its 56 years to date—with its tragic lows and brilliant highs—has a great deal to teach us.

Genuine revolutions are always fought for freedom, and that freedom, at least in modern times, is understood to extend to intellectual and artistic expression. But intellectuals and artists as a group famously resist an easy class analysis. The more traditionalist 20th-century Marxists, those of ‘‘real socialism’s’’ old Communist parties, developed decidedly conservative ideas about the cultural manifestations they believed should be prioritized; socialist realist painting, for example, was just the tip of the iceberg when it came to what they thought permissible and what they feared.

The Cuban Revolution emerged with more complex ideas. Ernesto Che Guevara, in his Man and Socialism in Cuba (1965) famously defended abstract art. Early on Fidel Castro urged artists not to reduce the complexity of their work so it would be understood by the masses, but insisted the cultural level of the masses be elevated to an understanding of the finest art. Fidel himself, as well as figures such as the Cuban film institute’s Alfredo Guevara, Casa de las Ame ́rica’s Hayde ́e Santamarı ́a, poet Roberto Ferna ́ndez Retamar, critic Ambrosio Fornet, and the country’s first and second ministers of Culture, Armando Hart and Abel Prieto, all had enormous faith in a population that was rapidly being educated, and defended more sophisticated experimentation and diverse opinions.

But prominent members of Cuba’s pre-revolutionary Communist Party (Partido Socialista Popular or PSP), such as Blas Roca and Juan Marinello, as well as functionaries Edith Garcı ́ a Buchaca, Luis Pavo ́ n and others who held positions of power on the National Culture Council (the Revolution’s first institution set up to manage cultural affairs) favored safety and mediocrity over experimentation in the arts. They feared difference and turned homophobia into cultural policy. This nefarious tendency reached a peak in 1971. An important nationwide congress on education and culture held that year explicitly denied the country’s homosexuals the right to be teachers.

A very important event, not just in terms of Cuban history but for intellectuals and artists throughout the developing and developed world, was the Cultural Congress of Havana, held in January of 1968. More than 600 thinkers, writers, artists, religious and political leaders, and community activists of note attended the event, as did over 1000 journalists. The meeting had been planned by the Cubans to encourage support for the Revolution’s efforts to sponsor liberation movements in the so-called Third World. But the greatest exponent of people’s liberation, Ernesto Che Guevara, met his death in the mountains of Bolivia just months before the Congress convened. The gathering inevitably became a mosaic of diverging views on how to move forward in view of this terrible defeat. It was clear to most cultural workers that there had to be a way to resist neoliberalism’s brain drain and efforts to control those in the cultural realm. But there were differences of opinion as to how this might best be accomplished.

For reasons that also have to do with cultural control, very little attention has been paid to the Cultural Congress of 1968. One of the virtues of To Defend the Revolution is to Defend Culture is that it devotes a great deal of space to that event, detailing arguments never before brought to light in an English-language book. I attended that Congress, and I had yet to read such an in-depth description of the five commissions, their respective sessions, papers and personalities. For this research alone Gordon-Nesbitt deserves our thanks. But she has done much more.

The struggles between old and new ways of experiencing culture were influenced, of course, by Cuba’s increased dependence upon the Soviet Union and socialist bloc. In retrospect, the Stalinization of cultural production was a danger that had to be overcome. The implosion of what we now refer to as ‘‘real socialism,’’ in 1989–90, left Cuba in a precarious situation economically. It also paved the way for saner and more adventurous minds to prevail in the world of philosophical ideas and relationships.

In the most difficult periods, control spawned censorship. And censorship spawned self- censorship. El quinquenio gris (the five gray years, in retrospect neither limited to five years and certainly much darker than gray) is remembered as a painful period for Cuba’s thinkers and artists. The Padilla Affair was indicative of the period. It is to the Cuban Revolution’s great credit that it has been able to examine, address, and remedy the excesses of those years without falling into neoliberalism’s dangerous traps. Cuban writers and artists, musicians, philosophers and architects, theater people and critics—many of them having been victims of the repression—led the historical exploration in an abundance of correspondence and broadly inclusive public forums. Their goal: to understand how the dark times had been allowed to engulf Cuba’s cultural milieu and make sure they could not happen again.

Gordon-Nesbitt’s meticulously researched book takes readers on a complex journey. Although referencing previous eras and those that are more recent, the author focuses in most detail on the years between the Revolution’s 1959 victory and 1976. Despite the book’s rather unwieldy title, and with as much detail as it offers, To Defend the Revolution is amazingly readable. At first I wondered: who except for a devout student of everything Cuban is going to be interested in all these personalities and allegiances, dates and meetings and changing policies? As I read, though, I found myself following the tendencies, pitfalls and rectifications almost as if they were a well-written history or detective thriller. It takes a talented and committed historian to carry this off.

The December 2014 reestablishment of diplomatic relations between Cuba and the United States has sparked renewed interest on the part of US citizens in the island nation just 90 miles off the Florida coast. Although predictably more a change in methodology than in policy, Cuba seems closer, more tangible and accessible. To level the playing field in a more robust way, the US trade embargo must be lifted and Guanta ́ namo returned to Cuba. Those don’t look like possibilities in the immediate future. But with loosened travel restrictions, more US Americans will now be joining people from other parts of the world in traveling to the Caribbean country and experiencing its culture firsthand.

Today all Cuba’s arts flourish in an atmosphere of freedom and possibility. A successful nationwide literacy campaign, subsidized publishing programs, and cultural events free and open to an eager, well-educated public, have been among the Revolution’s most impressive successes. It’s been a bumpy road at times. Gordon-Nesbitt invites us to consider its twists and turns. She gives us the data to do so in such a well-organized way that one wants to follow the story as far as she takes it—and beyond. Her introduction of Marxist-Humanism into the discussion of the road the Cuban Revolution has traveled is insightful and important. Her Chapter 8, ‘‘Towards a Marxist-Humanist Cultural Policy,’’ was particularly interesting to me.

A timeline of events significant to cultural developments in Cuba—both before and during the Revolution—a lengthy and very useful bibliography, numerous well- documented notes, and many photographs and tables, all complete an intricate picture. Jorge Fornet, one of Cuba’s most advanced cultural thinkers, provides a foreword that adds to the book’s authenticity, demonstrating his Revolution’s gratitude for a book that doesn’t hide the blemishes or warts.

PM Press has a worthy list of titles and authors. I salute a press willing to produce this kind of book: so needed but so beyond the range of most publishers these days. On the other hand, I wish a style corrector with a knowledge of Spanish had gone over the text; there are a number of typos and misspellings that, if fixed would have made for a more professional presentation. The index is also somewhat shabbily constructed, with several important references left out.

In the overall context, though, the above complaints are minor. Gordon-Nesbitt has given us a book that is both an extremely valuable research document and a good read, a very rare combination.