By Nicki Leone

BiblioBuffet.com

October 31, 2010

It’s All About Who Has the Guns

“These

were the mightiest men ever born upon this earth: mightiest were they,

and when they fought the fiercest tribes of mountain savages they

utterly overthrew them. I came from distant Pylos, and went about among

them, for they would have me come, and I fought as it was in me to do.

Not a man now living could withstand them, but they heard my words, and

were persuaded by them.”

–Nestor, to the Achaeans, The Iliad, Book I

1968.

Mention it and the words that come to mind are violent: Protest. Riot.

Militants. War. Assassination. Revolution. In the United States it was

the year of the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement, the

assassination of Martin Luther King. University campuses were disrupted

by student rallies. The Civil Rights Movement was never civil. The

Peace Movement, rarely peaceful.

Americans may be forgiven for thinking only of the troubles within their borders, but the unrest of 1968, the agitation, was worldwide. There were student protests against oppressive governments in Rome and Poland in the spring. In Berlin in April. Leeds University in England was brought to a standstill in May. May of ‘68 became the byword of student rebellion and wildcat strikes in Paris—what they called the Situationist International—a revolution of truly Parisian style, lead by avant-garde militants and using the arts to set up “experimental situations” (mostly of socialist design).

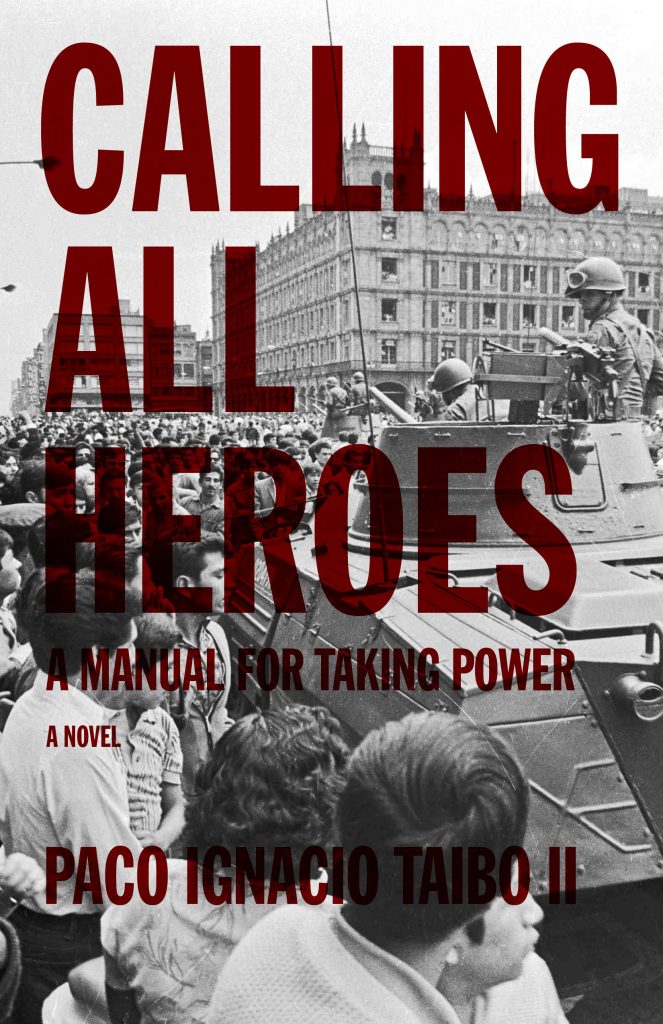

And, on October 2, 1968, just ten days before the Summer Olympics was to open in Mexico City, police forces shot into a crowd of students in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Tlatelolco section of the city, killings hundreds of people and effectively ending the rising revolts that had been orchestrated across more than seventy universities and preparatory schools in Mexico by an ad hoc organization of university students called The National Strike Council (Consejo Nacional de Huelga, or CNH). They were demonstrating against government interference in university autonomy—in effect, they were demonstrating for the right of freedom of expression, a right that had been ruthlessly curtailed as the government tried to prepare for the coming Olympics and tried to put on a good face for the rest of the world.

Student protests—like youth—have a way of flashing brightly and burning away to ash, but the CNH rebellion was better organized and more effective than the spontaneous rallies and riots that flared up in Rome, Berlin, or the campus of Columbia University, in New York City. The Beatles may have been singing about revolution, but the students at Vocational School #5 in Mexico City, the National Autonomous University of Mexico, or the Polytechnic Institute campus in Zacatenco were actually reaching for it.

The difference between a riot and a revolution, it turns out, is all in who has the guns. On the night of what is now called the Tlatelolco Massacre, over ten thousand people had gathered for a rally, hoping to bring their cause to the international community. (¡No queremos olimpiadas, queremos revolución! “We don’t want Olympic games, we want revolution!”). The protestors were surrounded by military forces—including armored cars and tanks. Snipers from the Presidential Guard shot into the crowd to give the military the excuse to fire, and panic ensued. Estimates of the number killed range from forty to over a thousand, with “several hundred” being the most commonly cited number. Most of the leaders of the CNH were arrested, the massacre itself was erased from official records, and the student movement fell apart.

In the way that the Martin Luther King assassination or Kent State has marked most Americans, the Tlatelolco Massacre remains a pivotal moment in Mexican politics—a point of anguish for those left to contemplate the ruins of their “revolution.” Paco Ignatio Taibo II was one of these. “At the beginning of 1969,” he writes “Gustavo Diaz Ordaz, vulture on a throne of skulls, reigned in Mexico. The student movement, massacred in the Casco de Santo Tomas, in the Plaza de la Cuidadela, in Tlatelelco, at Military Camp Number one—overthrown politically because it was unable to ally itself with the worker movement in the major cities—was in disarray. Thus began the long ebb after a struggle of 123 days in which thousands of Mexicans had come to life as human beings.”

Taibo II, who had been in the ’68 movement, did what a leftist intellectual, political insurgent literary critic and poet would do. He tried to put it all into a novel. The revolution, the defeat, the despair: “In defeat, we could only take refuge inside ourselves and in a bleak militancy for the hope of future fulfillment of the dreams of those 123 days. Under these deplorable conditions, this shortest of novels was created.” Taibo II then writes that he put the manuscript away in a drawer, pulling it out three more times over the next dozen years to rewrite it completely.

The result, Calling All Heroes: A Manual for Taking Power, may still be the “shortest of novels” but it lives up to each of the implications in its title. Although one can’t help but wonder if the embittered author who penned the first draft in 1969 would recognize the final product, published in Spanish in 1982, or the English translation I just read, which came out this year.

The book is about one of those failed revolutionaries, two years after all the hopes for the movement have been swept away with ruthless efficiency by that vulture on the throne of skulls. Néstor, the disillusioned revolutionary, has walked away from his political compatriots and taken up a career in what he calls “yellow journalism”—reporting on the trivially sensational rather than the truth. In that capacity, he runs afoul of a serial killer who, predictably, guts him and gets away. Néstor is left to recuperate in hospital with nothing to think about but past failures.

In

a haze of depression and drugs, Néstor decides that the revolution

failed because it had no heroes. When friends—equally failed

revolutionaries—come to visit him and sneak him cigarettes, their talk

is full of movies they’ve seen and the endless low-level corruption of

the state. “I’m going to get everyone together and we’re going to kick

their ass.” Néstor announces. Who? wonder his friends. The heroes, he

says.

And once this is decided, the novel slides effortlessly

into the kind of fantastic reality that seems so plausible in Latin

American literature and so contrived almost anywhere else. Néstor

starts writing letters, (well, dictating them—he’s still too weak to

write but not too weak to talk to a beautiful ex-girlfriend who brings

him things) calling to action the great heroes of the age. And no, we

are not talking about Lenin. His letters are to people at once more

familiar and more strange. Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday. Dick Turpin,

also known as “The Highwayman.” Sandokan, Prince of Borneo, and his

Tigers of Malaysia. The Mau Mau cheiftans of Kenya. The entire Light

Brigade. D’Artagnan along with Athos, Porthos and Aramis. Sherlock

Holmes (but not Doctor Watson. No, for this occasion Holmes is requested

to bring not the Doctor, but the Hound).

They all come, of course. For their own reasons, but they come. They are all heroes, after all. Men of action and steadfast heart. And Néstor from his hospital bed prepares to unleash all the fury of literature down upon the corrupt and unsuspecting forces of the government. (Holmes and the Hound get the job of assassinating the President).

Néstor does not call on

his former comrades to come into the plan. They have had their chance,

after all, and they failed. He also does not make detailed plans for a

revolutionary government—that is part of what failed in the first place;

everyone argued about the new regime before the revolution had even

been fought, much less won. No, Néstor’s plans are more direct this

time. Cause chaos. Make the vultures pay.

Remove the yoke, and

let the people rise. “You had to trust in the spontaneity of the

people,” he thinks, (because if you didn’t believe in that, then what

the hell could a veteran of ’68 believe in), and add to it the precision

of clockwork, a few touches of humor, a dose of the absurd, and a lot

of vengeance.”

It is a description that accurately describes the novel, which is told in short chapters that alternate between flashes of rising suspense and epistolary accounts after the fact. It may be a description that accurately describes how to take power. There is quite a lot of humor (the Mau Maus get lost), and quite a lot of vengeance. I confess I’ve never seen Sherlock Holmes in quite such a ruthless light. Néstor has given his side the guns, and put them in the hands of men not afraid to fire.

Whether or not the revolution is successful is for the reader to decide. It is certainly entertaining to read, and not without its many moments of absurdity, humor, and pathos. It was begun by men who tend to succeed in what they do (the vulture on the throne of skulls doesn’t have a chance). But its success is not measured in buildings stormed or police brigades slaughtered, however satisfying that feels. Success is in whether or not revolution is the fire in which people “come to life as human beings” — and that is something each individual human being can only do for himself.

But I can’t argue with the author’s idea that literature is the best way to kindle that fire.

Books mentioned in this column:

Calling All Heroes: A Manual for Taking Power (a novel) by Paco Ignatio Taibo II, translated by Gregory Nipper (PM Press, 2010)

Nicki

works for the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance, developing

marketing and outreach programs for independent bookstores. She has been

a book reviewer for several magazines, her local public radio station,

and local television stations. She was one of the founders of The Cape

Fear Crime Festival, and currently serves as President of the Board of

Trustees of the North Carolina Writers Network, and as Managing Editor

of BiblioBuffet. Plus, she blogs at Will Read for Food.