By Lee Mandelo

Tor.com

July 23rd, 2013

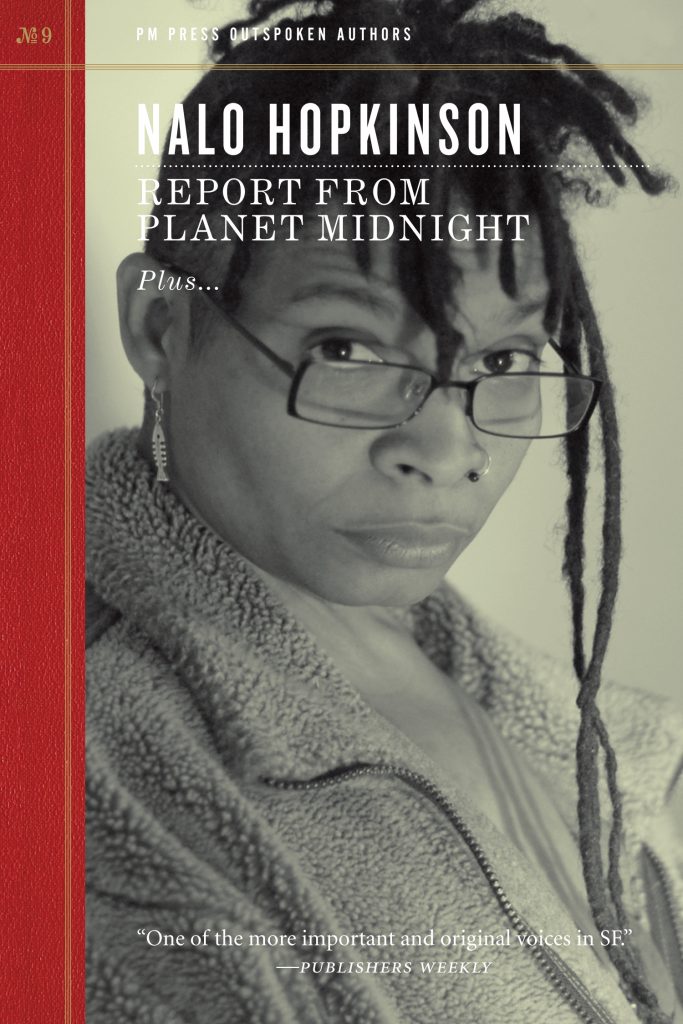

Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a space for conversation about recent and not-so-recent short stories. The PM Press Outpoken Authors series is—as I’ve said before when discussing their Ursula K. Le Guin volume The Wild Girls Plus…—pretty neat. These chapbooks run around 100 pages, collecting short pieces of various sorts from their authors as well as a long interview with them done fresh for inclusion in the book. The ninth in the series, released last year though I’ve just gotten around to it, features Nalo Hopkinson. Hopkinson is a writer whose work I deeply enjoy; so, naturally, I was pleased to see her included in this handsome series of little books.

Report from Planet Midnight Plus… reprints two stories, “Message in a Bottle” and “Shift,” as well as a transcript of Hopkinson’s 2010 speech to the audience at the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts, “Report from Planet Midnight.” The volume closes with the quintessential long interview and a detailed bibliography (one of my favorite parts of these volumes, actually!).

The two stories in this little book form an intriguing duet. The first is science fictional in premise and intimate in focus; the second is a riff on Shakespeare’s The Tempest that explores issues of race, identity, and family. “Message in a Bottle” struck me as eerie—primarily because of Hopkinson’s vibrant, realistic use of narrative voice. Though the thought of a child with the mind of an adult, sent back in time to curate artifacts lost to their own world, is discomfiting on its own, it wouldn’t necessarily be so much so without the narrator’s perceptions coloring our initial encounter with the child. The opening scene, where the young Kamla has crushed a hermit crab while collecting shells, is uncomfortable primarily because the narrator finds it so uncomfortable: his voice guides the reader’s own reaction to the fragility of life in the hands of a child who doesn’t know any better. (In hindsight, knowing that Kamla was not a child in reality, this scene is even more disturbing.)

The intimacy of the story—its realism, for lack of a better word—is another factor that makes its otherwise fairly simple premise effective and memorable. The narrator’s journey through his life, as he goes from single and a bit lonely to in love to becoming a father himself, is rendered in broad but deep strokes. Throughout this life, we have the continuing appearances of Kamla as she grows older, until she finally confesses the truth to him about her origins. His inability to quite accept the story, though it rings partially true to him, also struck me: it seems the only possible response of a very normal guy to something so shatteringly bizarre. Hopkinson has constructed, with “Message in a Bottle,” an excellent story about continuing to grow even as an adult—and about the odd, unbelievable things that can drop unexpectedly into our mundane lives.

“Shift,” with its reinterpretation of characters from The Tempest and its magical premise, seems initially quite different as a story. Following Caliban as his sister Ariel seeks him out for their mother Sycorax, it at first appears to be a story about personal reinvention through magic and trying to run away from a controlling mother. The narrative turns, however, midway through, as Ariel and Sycorax catch up to Caliban and his current girlfriend—and it shifts into another intimate story about family, identity, and the complex nature of perceptions of race in hegemonic cultures. At first we sympathize with Caliban, who is so very worried about escaping his mother and sister; when they catch up to him and reveal that they’re not trying to drag him home but, rather, giving him a lecture about responsibility and finding his own identity, things get crunchy. The reaction of the white girlfriend, too, as she meets his magical mother and sister, is fairly nonplussed: her issue isn’t with the family business, but with the fact that Caliban doesn’t know who he is or wants to be. She doesn’t want to be the one to make him something in the image of her own desires—she’d rather he come to himself on his own.

The idea of Caliban’s self shifting depending on how he is perceived, how he is seen in the eyes of the women he desires, is a strong one. I found myself lingering over it, and the implications for how cultural narratives—often destructive narratives from the dominant power structure—construct identity, construct perception, and influence even base ideas of self. It’s an intriguing piece that plays with magic and the old Shakespeare story but does something quite different with it in the end.

The other two pieces in the book are nonfiction: one a speech given after RaceFail ’09 dealing with systemic oppression, respect, and issues of “blindness” to societal issues, the other a long interview with Hopkinson about her work, her politics, and her opinions about various and sundry items. Both of these pieces were a delight to read. Hopkinson’s performative “Report from Planet Midnight” is sharply, incisively comedic—a favorite tactic of mine to read or see—while also pointing out, with grace, the failures and apologies we all make sometimes. It’s, despite that necessary sharpness, a gentle speech in many ways: an open speech, a speech that welcomes people to sit down and really think for a minute about their ideas, their behavior, their received knowledge.

I was particularly impressed by the deftness with which Hopkinson both calls out and offers empathy for the folks who behaved badly during that heated debate:

Some of you will recognize yourselves or friends of yours, or, hell, friends of mine in the actions I’m describing. It doesn’t necessarily mean that I hate these people. Believe it or not, my default is toward friendliness. People make mistakes. People say things they haven’t thought through. People do things they later regret. People hurt other people. People propagate systemic inequities because they don’t understand or care how the system works. I know that I do all those things. I’m learning that it’s what you do after you make the mistake that counts (46)

Most importantly, I think, the speech ends on a call for more openness and understanding—an understanding of the fact that “making room makes room for all of us” (49).

The interview cover similar territory in some ways—Hopkinson further explores issues of race, gender, and science fiction as a genre—but also goes into other realms. Discussions of folklore, teaching fiction, what sort of car Hopkinson drives (the answer: none), and getting older all come into play; it’s a deeply personal and fun interview that reads like an honest conversation between two people that the reader just happens to get to listen in on. Those are my favorite kinds of interviews, where the interviewer and the interviewee are having a good time and getting into depth with the topics of conversation.

Overall, Report from Planet Midnight Plus… is an excellent addition to the Outspoken Authors series. I look forward to reading more of the volumes—the two I’ve encountered so far have been equally great, handsome little chapbooks—and to seeing what other authors come next. Hopkinson’s volume is at turns hilarious and provocative, personal and political; it’s a great read, and offers a good sense of her work and her vision. I recommend it as an intro if you’ve never read any of her work before (but really, you should!), and as a pleasant addition to an existing collection of her work.