Interview with Pokret za Slobodu

(Freedom Fight Movement)

By Andrej Grubacic and Freedomfight (ff),

ZNet

May 28, 2010

AG: Let me begin by asking about the last round of privatization in Serbia. What used to be called in the state-socialist system of former Yugoslavia, “socially owned property,” is being enclosed and privatized. How advanced is this process of “privatization through bankruptcy” at the moment? And at the risk of sounding legalistic, how legal is this process of accumulation by dispossession?

FF: The privatization of socially owed property is almost completely done. The few big structures that remain are now turned into state enterprises, like the Bor complex (mines and mining industry) or the arms industry in ?a?ak, Užice, Kragujevac and so on. There are also some mid-level and small socially owed companies that are still not privatized, and last year the government decided simply to liquidate them. This liquidation is not based on economic reasons – it is a completely political decision to shut down all the remaining socially owed companies. The Ministry of Economy calls it “privatization through bankruptcy.” The decision is absolutely illegal. Serbian law on bankruptcy proscribes the causes for starting the liquidation process, and the government’s order to kill an otherwise well-doing company just because it is socially owed is not one of them. This decision was a cause for several protests last year, and the strongest group of workers who are still fighting is the one in Ravanica from ?uprija. Last summer its workers blocked the factory to prevent the government’s people from taking over the management. The protest gained strong public support, especially after the newspapers published the fact that Ravanica is not only the last factory in ?uprija up for privatization, but also the only one that still works, and works very well. ?uprija used to have several well known factories, and literally all of them were closed down or went bankrupt in the privatization process. The government feared this would initiate further debate about the success of the privatization process in Serbia, so they retreated from Ravanica and confirmed the old management as the official one. At this point Ravanica is the last remaining socially owed company in Serbia that remains in operation.

As far as the state owed companies, the government is planning to sell the pharmaceutical factory Galenika, Telekom Company, JAT Airways and Elektrodistribucija. They decided to sell Telekom this year, which caused very strong public protest. Both big unions of Telekom are against privatization, and they are supported by lots of intellectuals, some media (Republika and Balkan online magazine) and a former Telecommunications Minister. We can expect big fight over the issue this summer.

AG: Freedom Fight collective, or Pokret za Slobodu in Yugoslav, is a member of the Coordination Committee of Workers Protest in Serbia. What is the news from below? One of the goals of Freedom Fight, of Pokret, is to help create a horizontal, prefigurative, self-managed structure that would allow for a genuine workers self-activity – solidarity unionism. What is the reality of rank and file workers resistance, and what is the relationship with the old, vertical union structures?

FF: Last year’s wave of protests was caused by the results of the privatization process. Privatization failed to provide promised economic development, and after this problem was further emphasized by the global economic crisis, people began holding strikes and protests. Lots of privatization contracts were canceled (Zastava elektro, Vrša?ki vinogradi, Ikarbus…), and several of these workers groups formed the Coordination Committee of Workers Protests. Pokret za slobodu is also a member of the Coordinating Committee. Forming of this Committee was not only a reaction to the government’s policies, but also on the policies of the big unions. It was previously the union’s job to connect the workers groups that are protesting, but they instead choose to take the government’s side. During the protest of the Zastava elektro workers, we witnessed the union actually sabotaging the workers’ plan to organize demonstrations in front of the Privatization Agency’s (PA) building in Belgrade. Then Pokret za slobodu called Zrenjanin and Belgrade workers to help them – they organized demonstrations together, and that was the beginning of the Coordination Committee. The Zastava elektro protest was successful. The PA was forced to cancel the privatization contract, but two months ago they sold Zastava elektro again to the Yura Company from South Korea. Yura officials banned union organizing, and most of the old workers who were in last year’s protests left the factory. They feel that the new sale of the company is a kind of revenge by the government for the protest. Furthermore, the pro-Government press is now attacking them by saying that they are lazy – that ”last year they were protesting for their jobs, but when Korean company offers them jobs, they refuse to work!” On the other hand, the protest of another group from the Coordination Committee, Trudbenik gradnja workers, was unsuccessful even though they proved that their boss was severely breaking the privatization contract. The PA accepted their evidence, and it released the official hundred-pages detailed report on how the boss was breaking the law, but then they said, ”OK, you guys were right, he is robing both you and the state, it is outrageous, but we won’t break the contract“. Just like that. Why? Because this was a clear message for all the other workers what would happen if they rebel, and especially if they are doing it outside of the union structures. The cost of this for the workers was very high – more than 200 Trudbenik workers were sacked by the boss because of the protest. At the beginning of the strike in August last year they knew what would happen if they turn it into a protest against the privatization contract. But they took the risk, knowing that the canceling of the privatization contract was their only chance to get the jobs back. It was him-or-them, and they proved that the law is on their side, but now they are out, not the boss. At the same time, Zastava elektro workers are punished for their last year’s successful protest as well. The Coordination Committee is still far from being strong enough to help them, besides holding more protests, so at this point the situation doesn’t look good. However, we are expecting a new wave of protests this summer, and that would be the chance for our organization – Coordination Committee of Workers Protests in Serbia – to grow stronger.

AG: So is this the new focus of your current activity? Are there any efforts to document the experiences of last year and your struggle for solidarity unionism against the long theft we know as privatization?

FF: Besides our work within the Coordination Committee, Pokret za slobodu is now trying to broaden the network. We are now establishing contacts with peasants associations. They are the group completely repressed by the government because they don`t have a level of organization strong enough to fight radically against either the government’s measures that are destroying their economy, nor against the private monopolies trading with the agricultural products which are the fruit of their labor. This is very important issue here, since over 2 million people in Serbia lives only from agriculture as their livelihood.

We are currently working on a film and a book about last year’s protests, because we believe it is important to analyze what really happened, its continued significance and to give our side of the story. The Serbian press is writing about workers issues only from the perspective of big politics or big unions, and we want to show the perspectives of the people who were in the protests. These protests are not just another subject of somebody’s political agenda, they are coming from the people, and what we are doing is trying to help these people be heard.

AG: In my view, one of the truly “balkanopolitan” elements of the Balkan and Serbian society are the Roma – their struggle against hierarchical, state-imposed authority and regulation, against the market economy and systems of both state socialism and capitalism, along with their culture, are a powerful inspiration for dreaming another Balkans. On the other hand, and for this very reason, they were and remain to be the single most oppressed group in the Balkan states.

FF: Roma are the only group in Serbia that is completely left to its own fate. It is a desperate, catastrophic situation. The number of itinerant poor is now even larger due to exclusion mechanisms of the neoliberal state. Roma live in the streets, they collect trash and paper in order to survive. Some estimates put the number of Roma in Serbia at 600,000, although the 2002 census only registered 102,193 people as Roma. According to the UNICEF report on the condition of Roma children in the Republic of Serbia (2006), almost 70% of Roma children are poor and over 60% of Roma households with children live below poverty line. Children are the most imperiled, living outside of cities in households with several children. Over 80% of indigent Roma children live in families in which the adult members of the family do not have basic education.

AG: And in the meantime, the activist scene in Serbia is, in my opinion, very disconnected from these realities – or at least it was when I lived in Serbia. I hope that some things changed for the better since then, and that there is now at least an attempt to bring about a relationship of active solidarity, radical community organizing, and “accompaniment“ towards the situation of Roma in Serbia and the Balkans as a whole.

FF: The activist scene in Serbia is still weak and without influence, but there are some signs that this might change. Since the “transition“ process started in 2001, the bigest problem of the Serbian leftist comunity wasnt the fact that it was small, weak, outnumbered by Nazis and so on, but that it was incompetent and ignorant about local problems. Lots of energy was wasted on activities that had little to do with the actual problems of Serbian workers in “transition.“ And those problems were huge – too huge not to be seen and confronted. For that reason we can say now that it was almost lucky that most of the activities of the leftist collectives in the past decade went virtually unnoticed by the broad public. It was prety embarassing to have some self-proclamed anarchosyndicalist leaders preaching against privatization from the ideological point of view, but without a clue about the local context, as if they just fell in from another world. For years we were practicly the only collective that was working with the actual people on the ground in strikes. But since last year this has started to change: there are several Belgrade collectives now that are trying to support different groups of people in strike or in some other kind of protest, which is very significant because only by broadening our movement will the current leftist scene begin to make an influence, even though for the time-being it is still small.

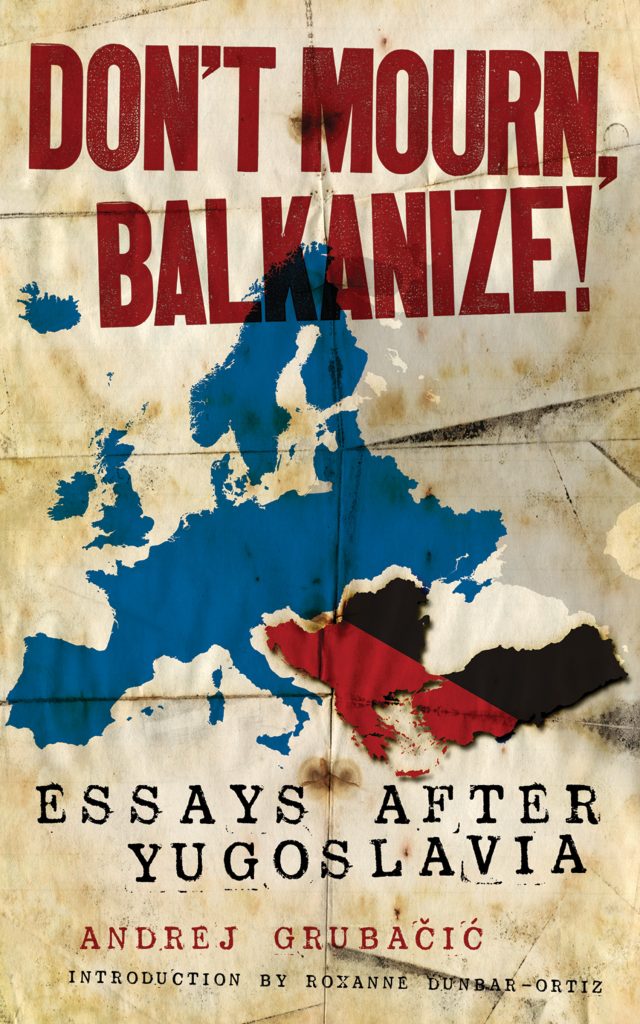

Andrej Grubacic is a member of Global Balkan Network, Industrial Workers of the World, and Workers Solidarity Alliance, as well as the author of forthcoming Don’t Mourn Balkanize! Essays After Yugoslavia.