By Leilani Clark

KQED

April 10th, 2016

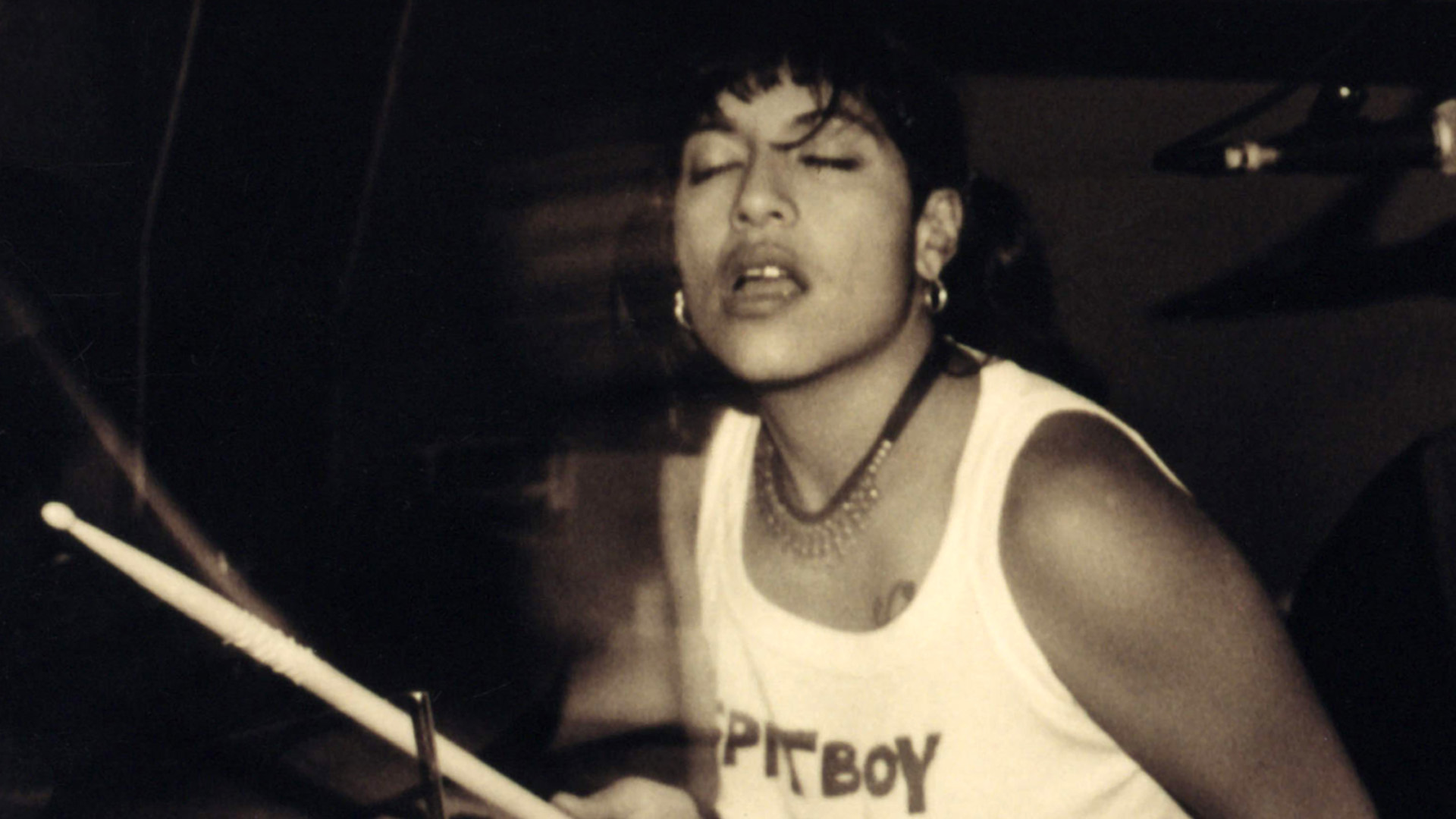

I first saw the East Bay feminist hardcore band Spitboy in 1993. I remember the moment the four women, the only ones on a packed bill, took the stage at the Phoenix Theater in Petaluma. Wearing ripped shorts, combat boots, Converse and worn tank tops, they were tough, intimidating, and mind-blowing with a driving, abrasive sound I’d never heard women produce before. Sure, I loved punk rock. But I’d never seen it done like this. Spitboy’s lead singer Adrienne sang about gender oppression, sexual violence, and the mismeasure of women in American society like a no-holds barred assault. It was exhilarating, hardcore, and life-affirming; I loved every second.

I idolized Spitboy from that day, adding them to a stable of bands that would inform my experience as a young feminist woman fronting an (almost) all-girl band a few years later.

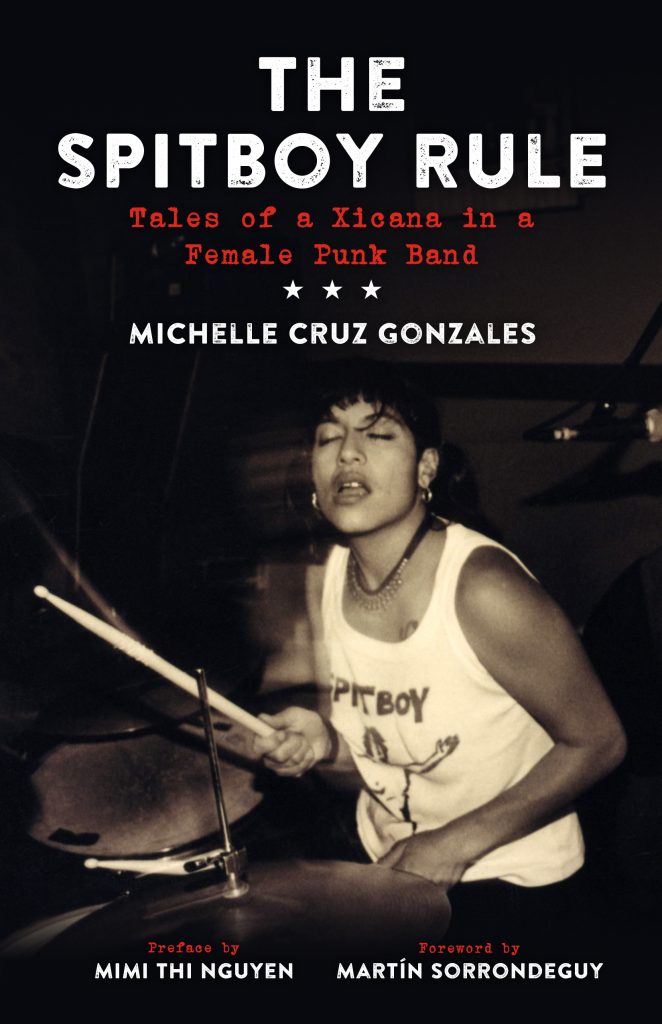

In her new book, The Spitboy Rule: Tales of a Xicana in a Female Punk Band (PM Press) Michelle Cruz Gonzales writes about being a “Spitwoman” in those heady days. Gonzales — known back then as “Todd” — was the drummer in Spitboy and one of the band’s founding members. She still makes her home in Oakland, where she lives with her family.

The book, based on a zine of the same name, doesn’t function as a straightforward narrative.

Rather, the collection of essays jumps around in time and consciousness, anchored by Gonzales’ reflections on the varied experiences of being a young, working-class Chicana woman in a well-known touring band at a time when women in punk rock were rare.

As such, it’s an engrossing account of a particular period in music history. A historical moment when, as Mimi Thi Ngyuyen writes in the preface, “some consciousness about women in music broke through, briefly.” (Read anything by Jessica Hopper for more on this.) Gonzales writes about her journey from Tuolomne, a “dysfunctional, limiting, broken” town in California’s Gold Rush country, to San Francisco, hellbent on playing music like her heroes the Clash — first with Bitch Fight, and later with Spitboy and Instant Girl. It isn’t an easy journey, and it’s exacerbated by class shame, a neglected Chicana identity, and sexist and abusive vitriol lobbed at Spitboy during live performances.

“As aggressively unapologetic women in a (still) bro-dominant scene, Spitboy shouldered both misogynist hostility and the burden of representation,” writes Gonzales, after relaying a story of one particularly disgusting comment from a male audience member.

What’s most refreshing about The Spitboy Rule is Gonzales’ ability to closely examine the class and race issues woven through the mid-’90s Bay Area punk scene. Yes, she found community, friendship, and unfettered artistic expression with the band. But, as she writes, she always felt like an outsider; the only woman of color amidst all white women. The only band member who didn’t come from a fairly comfortable middle-class background.

These cultural differences come to the forefront after the band stops to visit Gonzales’ grandmother in East Los Angeles. It’s a stop she later regrets:

Stopping had not been a good idea at all. We should have stayed on the I-5. I should not have suggested we veer off into the second-largest Mexican city in the world. I had made everyone uncomfortable, and now I was outside my body, seeing my adored Grandma and her shabby East L.A. home, which I’d always found tidy and comforting, her knick-knacks — which they probably called tchotchkes — and all her family photos of Mexicans, and now myself through different eyes, and I didn’t like it one bit.

Most working-class kids have experienced similar moments — even within the punk scene, where lots of middle class kids went to hide — the feeling of shabbiness, of not quite fitting in, which is disconcerting when you’re with a peer group that professes to accept pretty much everything except Republicans and SUVs. In truth, the punk scene suffered from elitism, mansplaining, and race/class privilege as much as any other cultural movement.

Gonzales writes honestly about being Chicana in an overwhelmingly white punk scene. “I didn’t often make references to being Mexican, a Xicana, in a mostly white band in a mostly white punk scene. It was just easier to try to blend in with my short hair, my tattoo, and my punk uniform.” She dates white guys (including Cometbus editor Aaron Elliott) and struggles towards an acceptance of her identity, first through learning Spanish, and later as an ethnic studies minor at Mills College.

There are victorious moments as well. Gonzales writes of the thrill of touring Europe with Citizen Fish, traveling to Japan for the first time where one rabid fan cried upon meeting her, and playing in New Zealand to enthusiastic crowds. All experiences she couldn’t have imagined as a young, isolated punk in Tuolumne, listening to the Clash and dreaming of England. Later, she meets Los Crudos, a Latino hardcore band out of Chicago that sings in Spanish and proudly displays their cultural heritage. “I began to feel more comfortable with my multiple identities,” she writes, “Spitboy drummer, feminist, Xicana.”

Gonzales is now in her mid-forties; Spitboy played that show at the Phoenix Theater almost 25 years ago. The stories and observations in The Spitboy Rule benefit from years of reflection, schooling, and life lived. This would have been a much different book if Gonzales had written it 20 years ago. It is a privilege to grow older, to have the chance to reflect on the formative struggles and building of consciousness that happens when we are young. And, for Spitboy fans like me, the true thrill comes from getting the inside story on the four radical women who took that stage in 1993 and blew us all away.