By Tessa Solomon

Daily Iowan

June 23rd, 2016

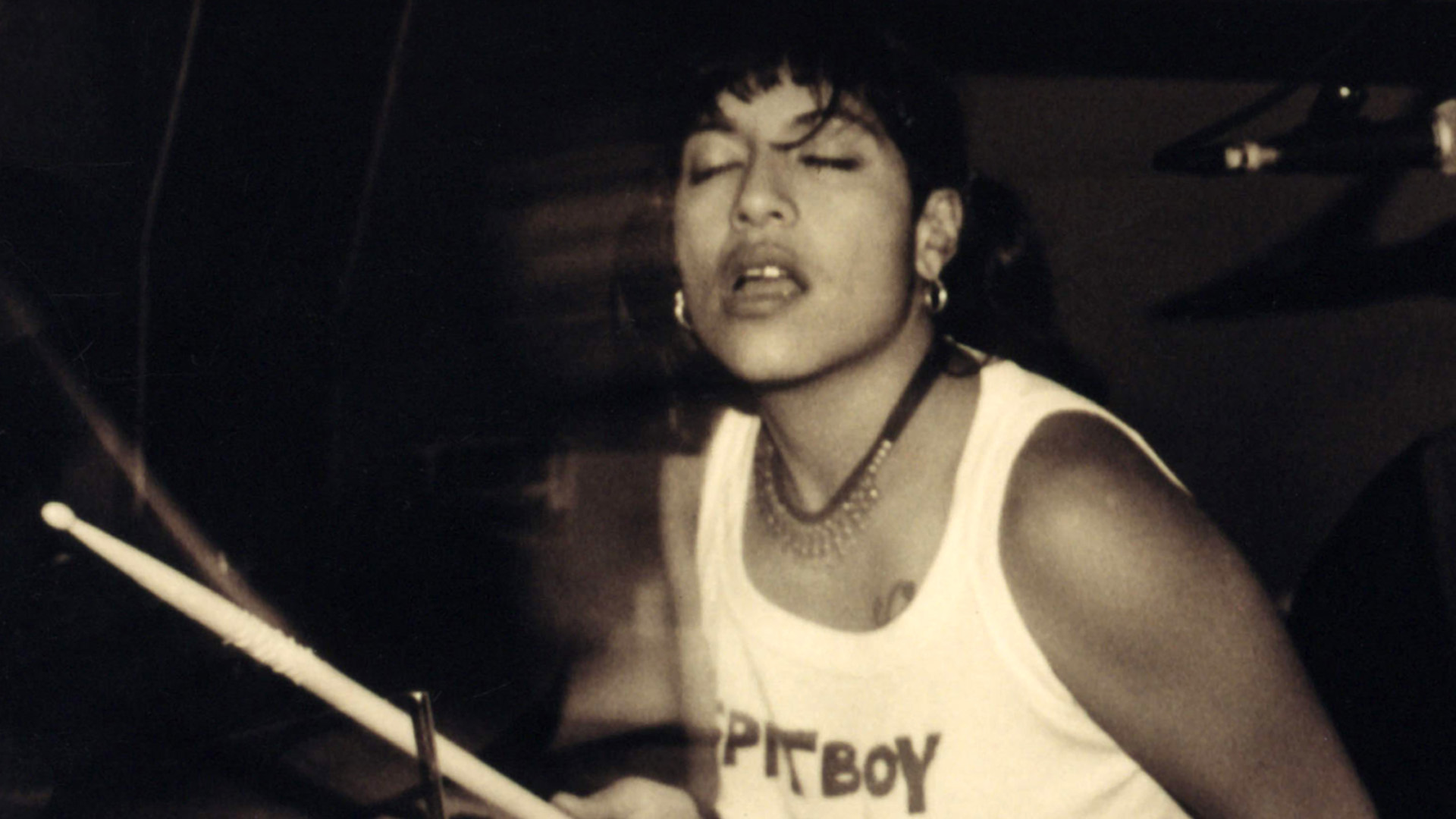

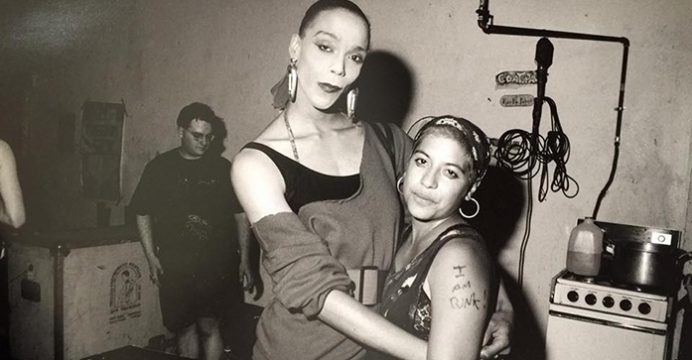

The camera shakes, capturing in its grainy frame four women on a dimly lit stage.

Their bodies are pierced, heads shaven, and demeanor unapologetic. They’re playing in a church basement, the dust and smoke in the air is tinted by the golden and crimson lights that hang above the stage.

Some people in the thick crowd bang their heads. Others thrash limbs, as if gripped by the raw, gloriously dissident, hard-core punk. A timestamp denotes: Toronto, Ontario. 1993. It is the first major tour of Spitboy, a pioneering group of the Bay Area’s ’90s hard-core scene.

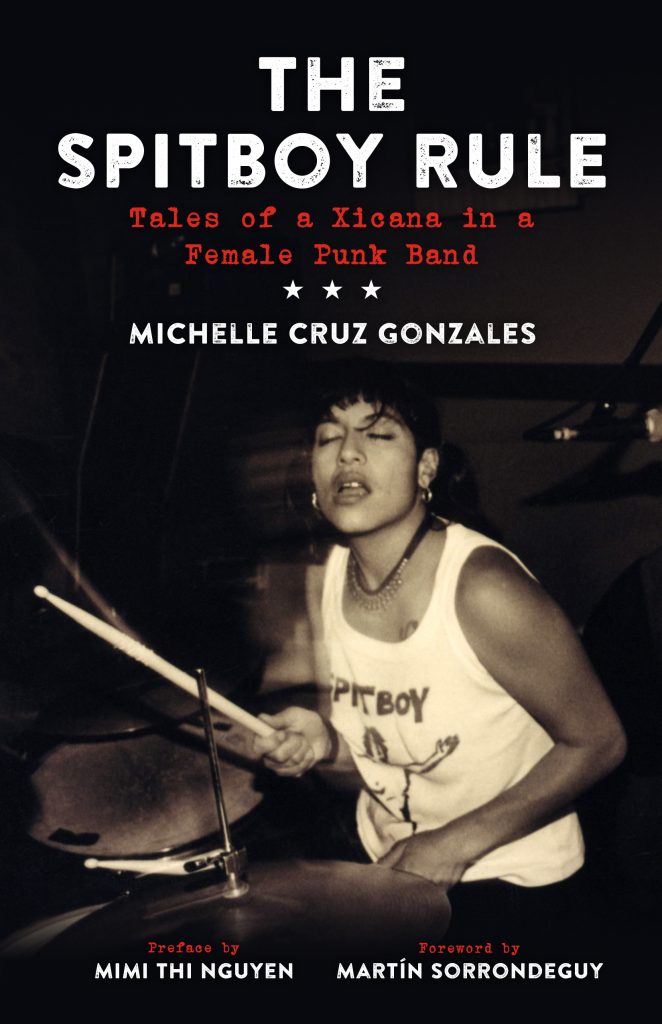

Until now, the band members have lived mostly in the memories of those who attended their raucous shows, but with the recent release of The Spitboy Rule: Tales of a Xicana in a Female Punk Band, they are on the cusp of immortality.

Author Michelle Cruz Gonzales, the drummer and a founding member of Spitboy, will read from her memoir at 7 p.m. today at Prairie Lights, 15 S. Dubuque St.

Her collection of essays delves into Spitboy’s conception and rise in San Francisco, a journey that entangles her numerous identities: punk, feminist, and Mexican-American. Loosely chronological, it begins with her childhood in a small California town plagued with racism and classism, an upbringing and environment that — despite longstanding cultural barricades — eventually led Gonzales to hard-core.

“The punk boys kept saying they were going to start a band, but they never did,” Gonzales said. “They would tell us, ‘Girls can’t play music.’ Well, we were doing it, and they weren’t.”

Hard-core is a genre defined by rhythm over melody; discord over harmony. Practitioners viewed Southern California’s post-punk sound as “poseur,” so hard-core guitars were distorted and amplified, while songwriting disregarded the typical verse-chorus structure. Their fuel was a furious desire to be authentic, to be heard, to always play louder, faster and, yes, harder.

“I had wished there was a female hard-core band,” said Gonzales. “I was trying to find a band like that, but then I realized I should form that band. I wanted to fill that void, to be the band we wanted to hear.”

After graduating from high school, Gonzales’ newly formed band, Spitboy, found that audience in the Bay Area. A variety of punk subgenres thrived there, finding a home in the Alternative Music Foundation, a music venue known in the crowd simply as “Gilman.” But despite the openness of the Gilman Street scene, hard-core was dominated by all-male bands such as Black Flag and Dead Kennedys.

“We were playing hard-core music, but we were women, singing about women’s issues,” said Gonzales. “And I was this female, Xicana punk drummer trying to find my way and not always feeling like I fit in.”

It was a chip on her shoulder that took years to shake.

“I always had a feeling of shame growing up poor. I had to prove that I didn’t fit into the stereotype of Mexicans,” Gonzales said. “But you put on your punk uniform and conform to this aesthetic, and when you do that, your cultural identity can fall away.”

While Gonzalez struggled to discover a happy intersection of personal identities, Spitboy combated an unwelcome association: the contemporaneous riot-grrrl movement.

“We didn’t want to be called girls,” she said. “Women in the ’90s Bay Area were very strong about being called women, to be looked at as an equal. Being called a girl seemed like going backwards.”

With respect to riot grrrl, the hard-core culture Spitboy embraced was different, both in sound and in attitude. This was a distinction Gonzales continued to emphasize years later.

“When all these riot-grrrl and rock memoirs started coming out, I realized if I didn’t try to publish my stories in a book, they would be lost in history,” Gonzales said.

It became a mission for her to document the countries Spitboy had toured, the people the music had affected, and the unusual schooling she experienced along the way.

“Punk was a great education,” Gonzales said. “We were writing these treatises on feminist issues and using it as a vehicle to get these messages out — that you don’t need to be a man or be white to play punk.”