By Michelle Threadgould

Remezcla

February 29, 2016

“Kiss the freak, faggot,” spat Travis at my friend David and me. Travis was the ringleader of the jocks at my elementary school. Even in the fifth grade I fucking hated that word: faggot.

I didn’t like being a freak either, but I knew I was one. I was one of two Latinas in my grade. I was curvy and had reached puberty early. It was like my breasts offended everyone; boys and girls in my class would stare, men would catcall me in malls or on the street, and my teachers would pull me aside and tell me to “cover up” because of my cleavage. Who the fuck has cleavage at 11 years old? I was a freak.

But David was not. He was the only person in my class who was nice to me.

“Don’t call him that,” I said.

“Are you gonna have your girlfriend fight for you?” Travis asked.

“I’m not a faggot,” David said, as if to himself. He looked no one in the eye. He just wanted to disappear. So did I.

Travis and the other boys pushed David into me. Again. And again. There was no reason to push back — because there was no escape, it would just start over again the next day. To them, we had chosen to be freaks, and they were enacting our just punishment.

I just wanted to learn to be invisible.

When I found hardcore punk as a teenager in the Bay Area in the early 00s, I loved that I could be one of the guys without being sexualized. My favorite band was Fugazi, and they didn’t believe in merchandise or wearing band T-shirts, because if you were into the music, you bought the record. Being punk to me wasn’t about wearing a leather jacket and Doc Martens, it was about saying “fuck the system” with a group of people who understood what that meant.

I was learning the art of being invisible.

So I wore a different kind of punk uniform: boxy T-shirts, jeans, Converse sneakers, and bandanas. I did everything I could not to look like a girl, not to stand out. I thought I was saying fuck the system while really becoming a part of it. I acted like one of the guys, dressed like one of the guys, and forgot that I wasn’t one of the guys. I didn’t want to be a punk girl, I wanted to be punk.

I was learning the art of being invisible.

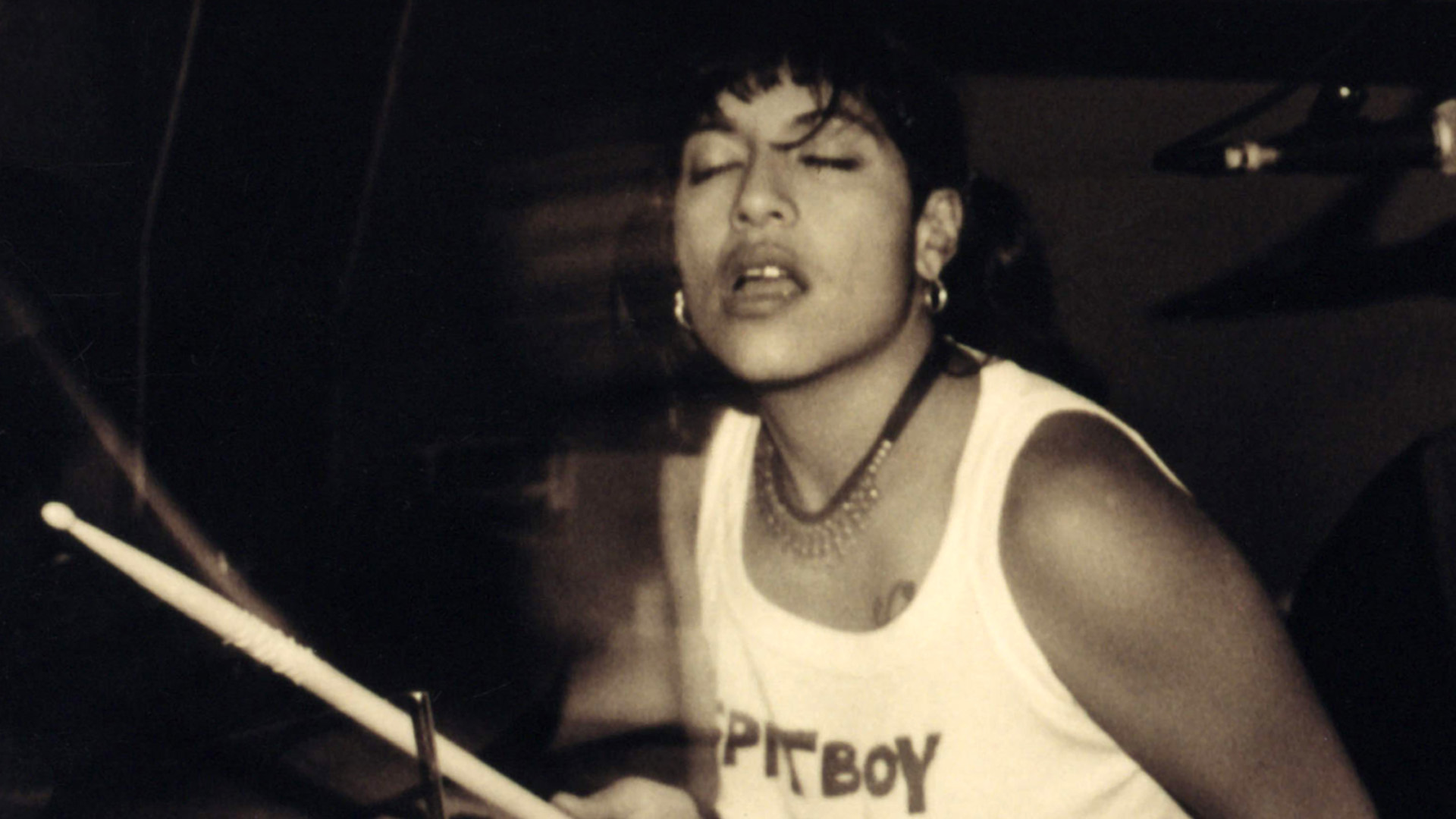

“Many of the riot grrrl bands, and not all of them, really used sexuality as a performance, and that made Spitboy [Rule] really uncomfortable. We were fairly asexual on stage, and that was by design, because 3 out of 4 of us had experienced some sort of sexual assault or sexual abuse as children, and we just did not want people looking at us like that. We did not want to be hypersexualized,” says Michelle Gonzales, drummer of 90s female hardcore punk band The Spitboy Rule. “I definitely internalized that many men would fetishize me, because of my dark skin, and because I was Latina, so that was one of the many reasons that I was uncomfortable with that, the use of sexuality as performance.”

“And even though it was the same message [as riot grrrl], you know, we were a hardcore band. So we weren’t doing this cutesy, bouncy, girl thing. Our music was not melodic and it did not have a bunch of harmonies. It was straightforward hardcore. And so, our performance onstage, unfortunately, was straightforward hardcore – you know, the way the guys did it.”

“If you want to prove your womanhood, shut up and spread your legs or play.”

When I met Gonzales in Oakland earlier this month, I saw so many of my own experiences reflected in her words. Though we came up in the Bay Area punk scene 10 years apart, we grew up with the same tension: a constant kind of code-switching between the women we were to our families, our friends, and to the public. So many fractured identities, unable to be whole at the same time. Meeting Gonzales wasn’t just meeting someone who got it, it was like looking into the punk mirror, at someone who knew all of my cultural references.

Spitboy was a force in the Bay Area punk scene, and in the scene at large. They shared a split record with one of the first American punk bands to sing in Spanish, Los Crudos, and toured with members of the Subhumans across Europe and Japan. When sifting through photographs of the band, you’ll come across pillars of the punk scene like Ian MacKaye of Fugazi, Aaron Elliott, the former drummer of Crimpshine, and the creator of the zine Cometbus, the ultimate chronicler of punk rock history.

Even though Spitboy was beloved and known in many punk circles, they were still told that as musicians, they “hit hard, for girls.” At one concert, when the band stopped their set because of violence erupting in the pit, a man called out, “Hey, if you want to prove your womanhood, shut up and spread your legs or play.” At the time, it was not uncommon for men in punk to tell women that they didn’t think of them as peers or even as people. It was not uncommon for women to be treated like they were good for just one thing.

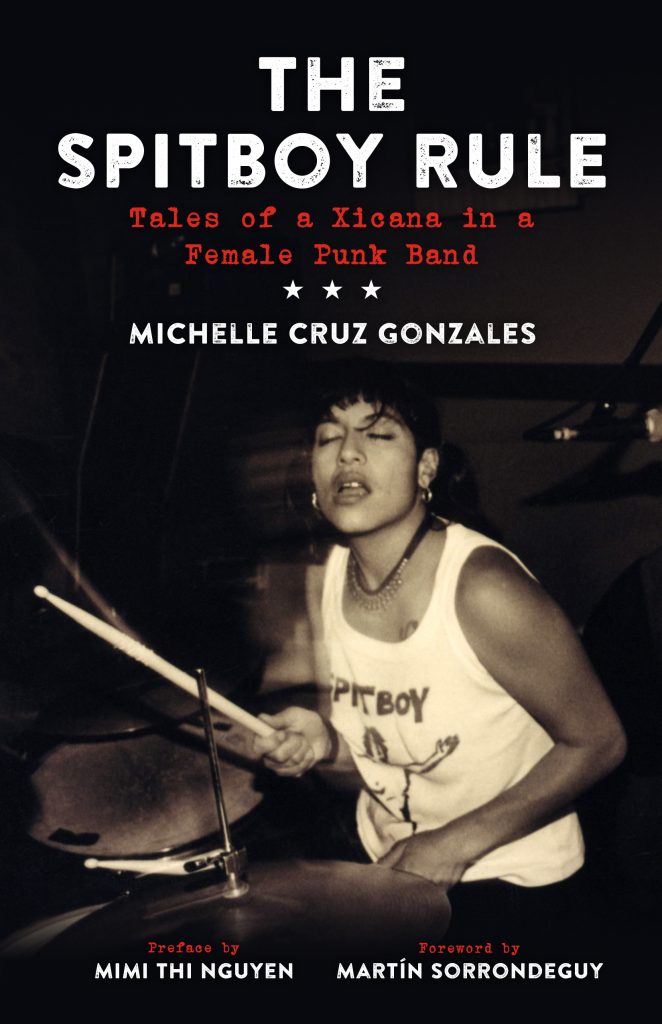

Gonzales’ new music memoir The Spitboy Rule: Tales of a Xicana in a Female Punk Band is as much about identity as it is about what it was like to grow up in a time where the language of intersectionality was absent and inaccessible. She captures what color blindness meant for people of color in the 90s, and how it translated into invisibility. Yet there was a double consciousness – a feeling that we existed in a colorblind society while we were expected to assimilate into mainstream whiteness.

Part of the richness of Gonzales’ book is her depiction of how these identities were prohibited from coexisting. When the band released the Mi Cuerpo Es Mío EP in the early 90s, a member of a riot grrrl group accused them of cultural appropriation.

“She objected to our use of Spanish for the title of our record and accused us of stealing from someone else’s culture, in particular the words ‘mi cuerpo es mío,’ which translates to ‘my body is mine.’ Apparently my body was invisible.”

Gonzales feels she didn’t have the vocabulary to communicate why these words felt like such a betrayal. She didn’t discuss why these words hurt her with her band. Instead, she metabolized and internalized them.

“In conforming to the nonconformist punk ways, adhering mostly to the punk uniform, I had lost something along the way, and I began to experience rumblings of discontent that I didn’t quite understand. I secretly listened to Linda Ronstadt’s Canciones de Mi Padre and sang along, holding long sad notes to words like that, like Ronstadt, [words] I only vaguely understood.”

I was 27 when I first heard Violeta Parra’s “Gracias a la Vida.” At the time, I would play it everywhere: at work, in my car, and at home while writing. I had somehow lived most of my adult life without it, though I don’t know how.

Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto

Me ha dado la risa y me ha dado el llanto

Así yo distingo dicha de quebranto

Los dos materiales que forman mi canto

Y el canto de ustedes que es mi mismo canto

Y el canto de todos que es mi propio canto

Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto

To hear Violeta Parra is to accept the beautiful poetry and ugliness of double consciousness. It is to revisit moments when you felt happy, yet very alone. It is both a thank you and a fuck you to the richness of life. “Gracias a la Vida” reflected the complexity I was searching for.

In the songs of Violeta Parra, Facundo Cabral, and Chavela Vargas, I found the same spirit of resistance that attracted me to punk, but this time it was in my language – not just the language of Spanish, but the language of living in-between.

I grew up speaking broken Spanish, but later along in my life, I’d sing these old folk songs to myself and learn new ways to communicate. I’d finally found the words that were inclusive of my identity.

When Martin Sorrondeguy from Los Crudos described Spitboy Rule, he said, “What so many never truly understood was that all four women brought much more than playing instruments to the stage. Each member had stories, struggles, pain, and together they were searching for answers which brought them together as a band, so go ahead, talk your shit. Spitboy just handed you the fucking mic, now what do you have to say?”

“Spitboy just handed you the fucking mic, now what do you have to say?”

Michelle Gonzales and The Spitboy Rule challenged the notion of who gets to speak and whose stories are told. Whether they wrote about misogyny, sexual assault, or violence against women, the band confronted the idea that women in punk needed to shut up and spread their legs or play.

Gonzales’ memoir isn’t just for fans of punk music. It’s for everyone who ever knew they deserved better and fought to reclaim their identity. It’s about the experience of playing your fucking heart out as a woman and finding the language to finally tell your story.

The Spitboy Rule: Tales of a Xicana in a Female Punk Band will be available for purchase this spring.