Marcus Colasurdo reading to music by cellist Kathy Bestwick at a benefit at the Hazleton Art League for the Soul Kitchen free community meals program in Hazleton, Pennsylvania. Photograph by Marc Charles Rooney.

If you saw Marcus Colasurdo in the last decade at a poetry reading in Baltimore, he might be hanging back slightly from the podium, about to read choice words on a tongue-tipped grin. You might remember watching him clad in a sleeveless “Children’s Defense Fund” t-shirt tucked into blue jeans. You would recall that image of him before he began to perform his own poetry and also afterward, because that would be the time you saw him alone, and before enthralled. Mostly likely, he had just hosted a few other poets during the evening, a group reading, as is his preference when he organizes events. You were probably there to donate five to ten dollars to a local homeless shelter, for an inner city, after-schools art program, or to gather books for under-funded libraries, or for New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, during a Gimme Shelter Productions reading, while enjoying music and poetry that evening. That’s a typical Marcus Colasurdo event. As Colasurdo reads his poetry, you are transported by the words, by their embracing sympathy, by its compassion for others, and passion for social justice.

…..Marcus Colasurdo has published several poetry collections, including most recently with French photographer Ollivier Girard, Equinox and Book of Numbers (Blurb, 2014 & 2016, respectively), as well as an underground novel named Angel City Taxi based upon his experiences driving a cab at night in Los Angeles, California, in the 1970s, before he moved back East around 1985. As Marcus states in the poem “Baltimore Solstice”:

……….The sound of the crowd

……….is sirens and dented

……….rainbows.

…..Later in the same poem Marcus writes:

……….At last, the moon.

……….Deep in the one-handed hours,

……….she eases through the sky high

……….dark curtains,

……….parting them

……….leaving silver at their feet.

…..On September 1, 2016, I drove up to Marcus’s hometown of Hazelton, Pennsylvania, where he mostly lives these days, to conduct this interview. We began chatting about what brought Marcus to poetry, and tried to touch on why his version of poetry is socially engaged. After a long day of work, with a smile on my face, and a good bottle of red wine at hand to share, we spoke that evening: G.H.:

Marcus, let’s start broadly. What brought you to poetry? Marcus:

I grew up in a house with books in it. My two older brothers, Jerry and Joe, were both readers. One was an actor, one was a scientist. Consequently, our bookshelves held works by Tennessee Williams, Eugene O’Neill, Albert Einstein, and Enrico Fermi. Books were respected in my life when I was growing up. My early exposure was being able to go to a bookshelf and being able to pick up, say, “Macbeth,” at age ten. I grappled with that, and was drawn into Shakespeare’s language, around age eleven, into his verse. I was also an all-star shortstop in Little League. I remember being in full uniform, with two hours to kill, and a lot of energy, picking up “Hamlet,” reading, sitting on the bench, waiting for the rest of the team to show up for batting practice. G.H.:

Were your parents literary? G.H.:

My parents were working-class people. My father was a coal miner for a long time, until he got black lung. My father was also a card player, he was a gambler. My mother was working in a textile factory; she was a seamstress, then she was a switchboard operator, and a great mom too. Not particularly literate people—they were too busy. Marcus:

What made you start writing poetry? When did you start writing poetry? Can you provide an example of a memory about you writing poetry early on? G.H.:

That’s a tough one. I remember one of the first poems that I read. I was a walking person, and I grew up in a small town—an industrial blue collar town, ringed by coal mines and by bits and pieces of the old Pennsylvania, its vast forest. I spent some of my childhood, especially in summer, running in the woods, but also in winter as well. One of first poems that struck me, while walking and just ducking into the library, was “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” by Robert Frost. That poem— it just hit me, because I had walked in the woods on snowy evenings. I know the language captivated me, just as the language of “What a piece of work is man” from “Hamlet” took hold of me. Who knows, at eleven, twelve, what you understand? It’s the mysterious magic of poetry. Poetry is not about explanations, it’s about feeling it as somebody. Marcus:

T.S. Eliot said it. G.H.:

Yeh, probably true. Marcus:

Eliot wrote, “You can understand it before you comprehend it” in his essay, “Tradition and Individual Talent.” G.H.:

Yes. Marcus:

Which is another way to say, “You feel it before you can articulate what you feel.” G.H.:

Earlier, before we began recording, you mentioned Langston Hughes. That’s somebody I need to mention, because he was one of the early guys who influenced me. I came across his poem, “Harlem,” in the library. I didn’t know exactly what it meant; it was short and it seemed extraordinarily intense. It’s the raisin in the sun— the dream deferred. There was something about it that I understood. I don’t know why. Partly because my family was poor, I think. That’s another magical way that poetry infuses itself into you. It crosses all kinds of barriers, because of its transcendent language. When people do it marvelously, like Hughes does it in “Harlem,” it transcends color. It’s about color, it’s about the deprivation that black people have gone through in this country, but it hit me. I was twelve years old at the time. Marcus

HarlemHarlem

…….

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like in the sun—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet? Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

Langston Hughes G.H.:

When did you go from reading and being inspired—by Frost, Hughes, Whitman, and others—to writing and performing? G.H.:

Performing was a long time in the future. Writing, around sixteen. Marcus:

Did you show your family the poetry? G.H.:

At age 18, I hitchhiked to California and stayed there for a long time. Lived in Los Angeles and San Francisco. During that time, I was working on anti-Apartheid and anti-war stuff, but in LA for some bizarre reason, writing of poetry started to solidify. It became a louder and louder voice in my ear. I was pretty young, in my twenties. Marcus:

What era was this? What decade are we talking about, your youth? G.H.:

I left Hazelton in 1975, so I was twenty-two.

Marcus:

G.H.:

We’re here to talk today about activism in poetry. Just based on what you’re saying, Marcus, it seems like activism or politics—maybe I’m not getting the right word— were always of central concern to you, is that right?

Well, my father got sick and was not able to work for many years, like five, seven years; hospitalized. Black lung. It led to lots of other problems. We were broke, I mean we were really fucking poor, where it was like Aretha Franklin’s line, people “running out of food and I ain’t lying.” Marcus:

I grew up, it was the tough years in the late ‘50s when the coal mines started closing down; this town became an unemployed place. Everybody is unemployed. My father happened to be unemployed and sick. We were for a while on what they used to call “relief,” and that now is referred to as welfare. That was pre-LBJ, before there were food stamps. We were scrambling. I remember actually eating ketchup sandwiches. Nasty shit, we were poor.

That has created a relationship, for me, of siding with the underdog, because I’ve been there. I relate to underdogs: people through no fault of their own get the short end of the stick. That is such a test of human imagination. How do you survive? How do you survive with dignity? How do poor people survive with dignity? It’s a question that still haunts America. .

You have answered my follow-up question in a way, but how does that real life experience relate to poetry? G.H.:

I’m blessed because I grew up in a house where books were respected, and where there was all kinds of reading going on, especially with my brothers, and the circumstances that my family was in. The bookshelf was quality, and my family had zip. We were as broke as motherfuckers. That’s odd, right? Poetry I think grew out of that crucible of coming together of two vastly different circumstances.

The mind was full and the belly was empty. Marcus:

Correct me or adjust what I’m about to say, but was poetry becoming a way for you to deal with and understand these things, or something different? G.H.:

I don’t know how that works exactly. I think it was a way of explaining the inexplicable. Looking for greater forces at work. I dreamt of . . . universality. Once you start that journey, you start talking to the universe . . . and it’s not always about politics. It is something vaster. Marcus:

Based on what you’re saying, does broadening horizons relate to activism? What would you say about the intersection, or divergence, of poetry and activism? G.H.:

I would say that Gimme Shelter Productions—how it brings together poets, dancers, musicians, sculptors, videographers, all kinds of people—to put on shows to benefit struggling organizations that service the community’s hurting, wounded people with food programs, shelters, after school programs—does this in real time. Marcus:

To date, we’ve had about 130 shows over more than a decade. So the confluence of art and activism, I think, is a matter of the imagination of the heart; it’s allowing the heart to have a fucking imagination, and that means, how do you behave in the world?

Now this kind of work is not hugely supported by institutions. But let me take a minute to give kudos to The Puffin Foundation, who have given us the seed money to plant, cultivate, harvest, and distribute fresh vegetables to homeless kids in shelters. To watch a child’s face light up when he bites into a fresh cherry tomato—that’s poetry, no?

…..It was refreshing that night to speak past midnight about poetry. But that is usual with Marcus Colasurdo. I met Marcus around 2005 when he was hosting poetry workshops out of his home. We began a friendship through my participation in Gimme Shelter Productions, their fundraising readings, through talking about poetry, and through sharing the writer’s journey along the way. Later, Marcus’s poems were included in Poems Against War magazine, which I founded and published, including three of his poems in Poems Against War: Bending Toward Justice (Wasteland Press, 2010).

…..His poem for anti-war activist Cindy Sheehan still stands out. Ms.Sheehan lost her son in the Iraq war before she became involved politically and became opposed to the Spring 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq. The poem appeared in Poems Against War: Music & Heroes (Wasteland Press, 2007), because it is a fine poem and Ms. Sheehan is a hero. The poem, titled “Sheehan,” opens:

…………………………………………Eventually the telegram.

……………………………………………………And

…………………………………………the mother is alone.

…………………………………………Too often she is alone

………………………………………………….in this feral cycle of days

…………………………………………When the lights go down

…………………………………………and photographs are not enough

…………………………………………what sleep awaits her?

…………………………………………Cape on coffin.

…………………………………………Medal made in China.

…………………………………………Sincere regrets.

…………………………………………How would you dream?

……Marcus is known for having co-founded Gimme Shelter Productions, a motley group of rotating poets who put on poetry performances to raise money for various causes, from building wells in Africa through Lutheran World Relief, to sending books to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, to opposing the mad lust for war. More recently during the years 2011–2016, Colasurdo has founded and supported “Soul Kitchens” in both Baltimore and Hazelton, to feed the hungry and build community in the process. These Soul Kitchens operate with a culinary panache and human heart. The Baltimore Soul Kitchen at Govans Presbyterian Church on York Road feeds hundreds of people every week.

Soul Kitchen flyer for Annual Fund Raiser at Govans Presbyterian Church in Baltimore

…..If you saw Marcus Colasurdo in Fall 2016 in Hazelton, you probably would not see him at home in his apartment writing, but rather organizing the nearby “Soul Kitchen” to feed the hungry. You might find him in one of the Latino bars near his apartment, the one that he likes best, red wine on ice in hand. You would see him near the bar smiling through his goatee and spectacles, humming to smooth bachata music, talking to everyone. As we sat talking, summer eased to September’s cooler midnight breezes as we continued our interview and spoke more about the founding of Gimme Shelter Productions: Marcus:

Gimme Shelter grew out of Urban Mobile Artists. It is a group in Los Angeles that I started along with Marcelle Brandler—one of the best unknown poets in the United States. When I came back east in 1997, I went to Baltimore, and started Gimme Shelter by going to poetry readings. .

From being part of Gimme Shelter I have observed that it is always organized around some sort of helping of other people. Is that correct? G.H.:

Absolutely. You know when you don’t eat in over 3–4 days you start hallucinating. You can think you’re anything from Jesus to Joan of Arc? You can also think you’re invisible. Marcus:

How does poetry address that kind of need, Marcus?

G.H.: Marcus:

Poetry addresses the need because you can do things that benefit people with it. If you do your work right and if the people that are onstage are committed and passionate and rhythmical and good, folks will come out and see them. They’ll pay money to see them. The money goes to a place like Kids On The Hill after school program. Goes to a place like Manna House that feeds and employs people. Goes to a place like Christopher House for their job placement program for homeless people. Place like House of Ruth for battered women. There’s a million of them, fortunately and unfortunately.

There is a direct connection between poets and folks who are hurting. One of the things Gimme Shelter did was to organize the writing project in Salvation Army Booth House. We worked with young, 10- to 14-year-old homeless children who were encouraged to present their poetry and perform. We put together a book of their poetry. There’s something about being able to see your name on the written page that these kids delighted in. Their works were really wonderful.

Throughout the years, we’ve done hundreds of shows. For the Easton, Pennsylvania Boys and Girls Home, Delaware Department of Corrections Library, Mercy Children’s Healthcare Outreach Program, Winter in America’s clothing distributions, United Workers, who won the contract for Baltimore stadium workers. The list goes on. We’re international because the whole thing is that we are all brothers and sisters on this planet or we ain’t right. .

If I ask you, Marcus, are you your brother’s keeper, what would you say? G.H.:

It’s inevitable, I believe, that you have to answer with John Donne, that no man is an island and it’s interconnected—all of it. Marcus:

Okay. So how does poetry fit in? G.H.:

I think anybody, everybody has their own answer. Marcus:

Sure, sure, but I’m just asking for your answer, Marcus. G.H.:

My answer is ambivalent. Because, as a poet, I’m constantly searching—my soul, my heart, the world around me—searching for beauty, for balance— Marcus:

Okay. G.H.:

Am I my brother’s keeper? Marcus:

I’m going to interrupt you, Marcus. It doesn’t sound like your answer is ambivalent because you’ve spent decades focused on poetry and connecting poetry. Not just using poetry but connecting poetry to other people and the real lives of other people. G.H.:

You know that’s interesting. Because if you read enough poetry internationally, you read some people like Pablo Neruda or Octavia Paz, particularly the Central and South American poets who have written extraordinarily moving verses about being your brother—maybe not your brother’s keeper—but being aware of the world in a way that recognizes that the realities of the world can often be really harsh to people who are innocent, who are wounded. Sometimes enchained. If you’re alive, there are many ways to look at it. So I don’t have to tell anybody what to do. Marcus:

Must poetry be engaged, then, with the situations of our brothers and sisters? Is that correct? For you? For your approach to poetry? G.H.:

I mean for me as an individual writer, I write politically engaged poems. I write a lot of very private poems. Poems about sunset and sunrise. One of my secret desires as a poet is to write the perfect poem about a sunrise and about a sunset. So far, perfection eludes me. Marcus:

But if you live in the world and you walk around in the world, you see people who are wounded. And should they be wounded? Think about why the greed of the few has become one of the behaviors of false gods who are accepted as “successful”, as our rulers. :

Back to your own writing and writing life, when I first met you, Marcus, you were teaching. It was around 2005 and you were teaching poetry workshops out of your house. When did you get into teaching? Your way of teaching wasn’t so much teaching as sharing and reading poems. G.H.:

No, I wasn’t teaching at all— Marcus:

It was a teaching— G.H.:

It was a workshop— Marcus:

It wasn’t traditional teaching. It was sharing, creating a space for people to share their poetry. You always opened to workshop with a poem or two that you really admired. You always offered gentle advice or just feedback on poetry. When did you start doing that? G.H.:

When my dad died in 1989, I came back from LA and helped my mom through it. They had been married many years. I decided while I was here that I was going to finish my school so I went to Bloomsburg University and did my last two years. During that time, among friends and others, we all exchanged our art, and held salons in our apartments, sort of “moveable feasts.” People would bring guitars, bring their poetry, sometimes like video stuff. It was great. Marcus:

At the same time, I was working at the Key Stone Job Corps, where I formed a theater and writer’s club for younger folks. I recognized poetry’s impact right there. .

How so? G.H.:

Writing, falling in love with art, finding one’s own voice is a weapon against the emotional clamp down. That the life of the heart, intellect, the soul is not important because it doesn’t make money. Poetry is not into dollars and cents, it’s about the soul. Marcus:

In America, poetry is generally a dreamer’s job. Now the question is, what is a dreamer? What are you dreaming? I’m thinking of John Trudell, the poet, you know. I’m thinking of the other traditions like Whitman’s inclusive definition of beauty. It’s about being in a dream; the dream is exquisite. Right? Because it’s the possibility of universality. All its myriad forms. I’m interested in the mandala. Which is the circle of many cultures.

Poetry is sort of the messenger of the universal to the individual human heart. .

What else would you say? G.H.: Marcus:

Never give up. Never give up. The scribe is a necessary part of our sanity. I mean for us as a species, without poetry, there is no place of reverence. Without reverence, the relativity of all things becomes a human guess. That’s not enough. I seek the sacred, the extraordinary in the ordinary, that “there is a deeper world than this.”

…..By this time, we had finished the bottle of wine. We had listened to Bob Dylan’s Self Portrait, Bruce Springsteen’s Wrecking Ball, a mix tape, and a bit from Lou Reed’s 1990s concert album A Perfect Night in London. We had spoken about T. S. Eliot, Allen Ginsberg, Mathew Arnold’s “Dover Beach,” Langston Hughes, Wordsworth, and breezed across other poetry close to us. Mr. Colasurdo yelled at me on a few occasions. He didn’t like one question. He cheered on another. I yelled back. That’s how we often discuss poetry. Tonight was no different.

…..At some point, Marcus Colasurdo called for poets to address today’s crises, especially global warming and racist intolerance. We spoke about this while the recorder was off. So, I resumed the recording and brought us back to these remarks, sometime before 2 a.m.: G.H.:

Can you just say that again? Why do we need right now a Shelley or a Byron or somebody who can, who’s romantic—? .

Epic! Marcus:

Who could do that, sum it up? Tell us where to go? G.H.:

Yes. That’s what an epic is, or at least sum it up and leave us with a puzzling and existential legend in our heart. Marcus:

Make us face it, too. G.H.:

Make us face it. Make us face what’s going on. Poetry, if nothing else, tells the truth in the viscera. This is why poetry will never end. It’s not a trend. It’s not on channel 7 yesterday. Marcus:

Poetry is timeless because it’s not about any kind of cover-up. There are no lies in poetry. Right? It’s not about makeup, it’s not about cover-up. Poetry’s about baring it all. .

As best you can. G.H.:

Yeah, and if you fall on your face, you fall on your face.

Marcus: G.H.:

One of my favorite modern sonnets is by Robert Lowell. He wrote that one sonnet where he references his own writing and hopes he he will have earned his place “on the minor slopes of Parnassus—“ The opening lines are beautiful:

Like thousand, I took pride and more than just,

struck matches that brought my blood to boil;

I memorized tricks to bring the river to fire—

somehow never wrote anything to come back to.

Can I suppose I am finished with wax flowers

and have earned my grass on the minor slopes of Parnassus. . . .

:

…….

Wow, nice.

Marcus:

It’s not just about writing the perfect poem, it’s about writing, it’s about reaching out. But back to the interview: what do you think some of the struggles are right now that must be confronted— G.H.:

One thing that strikes me about the United States in 2016 that struck me about Apartheid-era South Africa toward its end is I keep seeing funerals. I keep seeing funerals of black people, generally speaking, on the TV. Yet in the resistance and change happening to stop that, to change things, what I see is a remarkable. . . . Marcus:

You’re talking about— G.H.:

Knowledge of history. In this case, slavery. Marcus:

You’re talking about human intolerance— G.H.:

Poetry talks about all of it. You can think about some of the poetry of Maya Angelou, or her novel Why the Caged Bird Sings. I know why the caged birds sing. You’re a fan of Langston Hughes. You think about some of that. I just read “The Weary Blues” and “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” to prepare for this night. It’s good we’re talking about “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” by Langston Hughes. What an extraordinary fucking poem. Marcus:

Yeah, my favorite poem, when I was 16, was his poem, “The Ballad of the Landlord”— G.H.:

It’s a Depression era poem— Marcus:

Well, it talks about the unfairness of our system of rent, of our economy, and I don’t know why it struck me at 16, but it did. It’s a fundamental portrait of that. And as you have talked about tonight, that’s still going on— G.H.:

I love that you said “I don’t know why that struck me at 16.” I know exactly that feeling. Marcus:

It just did. Going back to global warming—why is that something we need to face in poetry? That may seem obvious, but let’s just pretend that’s not obvious. G.H.:

I don’t know exactly. I think that part of the soul that I have as a poet is being blown away by this earth. Talk about sunrise, sunset. I love the Atlantic Ocean, I love the Pacific Ocean, I love the Rocky Mountains, I love the Grand Tetons, I love the Pennsylvania Grand Canyon at Wellsboro—it goes on and on. Marcus:

As people, certainly as citizens, as poets, we have to be engaged. But before we end this, let me get back to Gimme Shelter. As you know, in the last few years, we have segued into the creation of the Soul Kitchens, where people come together to create and offer free community meals. We have one in Baltimore that’s been going on for five years and fed up to 4,000 people a meal at Govans Presbyterian Church. Then we established a Soul Kitchen in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, a hard-hit anthracite coal area that’s been four years going now. The idea of presenting food as a work of art . . . we’ve been conscientious about it. It isn’t bologna sandwiches. It’s A to Z! It’s full meals and carefully prepared with artistic flair. People are eating good meals, and it’s included them in the process of set-up and breakdown and sometimes even in cooking, so there’s a little bit of that involved. Often folks who come to eat end up becoming part of the work teams.

Especially in Baltimore, we’ve had an open mike in the church that we do it in, at Govans. There’s a piano at the ready, and anyone who wants to bring in their work or their music or their poetry is more than welcome. Art and human need are not separate. They are intertwined. A world without poetry is starving for real. People need sustenance from A to Z.

Poetry is heart; it is how we speak when we face the doors of sorrow, or approach the gates of joy. . . . It is what we sing when we fall in love.

Soul Kitchen flyer for free community meals at Govans Presbyterian Church in Baltimore

© G.H. Mosson

G.H. Mosson is the author of two books of poetry, Questions of Fire (Plain View, 2009) and Season of Flowers and Dust (Goose River, 2007). His poetry and literary commentary have appeared in The Cincinnati Review, The Tampa Review, Smartish Pace, Rattle, Measure, and previously in Loch Raven Review. Some of his anti-war poems were published in the journal Poems Against War (see pdf sampler on the web at http://www.poetryandpower.org/uploads/6/9/9/2/69925491/paw12.sampler.2003-2008.pdf). His poetry has been thrice nominated for the Pushcart Prize. He has an MA from The Johns Hopkins University Writing Seminars, where he was a teaching fellow and lecturer (2003–2005). Mosson is a writer, lawyer, father, and lives in Maryland.

Marcus Colasurdo is the author of 12 books including the underground classic Angel City Taxi. He has, over the years, worked in various jobs, including teacher, cab driver, bartender, construction worker, waiter, Job Corps counselor, features writer (Baltimore Chronicle), and house painter. As a writer for page and stage, Colasurdo is the founder of Gimme Shelter, a Baltimore-based performance group that does benefits for groups that work to alleviate poverty in our communities. Colasurdo is also the founder of Soul Kitchen, a free meal program that has served delicious, nutritious meals to needy folks in both Baltimore, Maryland, and Hazleton, Pennsylvania, for over 5 years. His recent collaborations with renowned photographer Ollivier Girard can be found on http://www.blurb.com/bookstore or by contacting Marcus directly at [email protected].

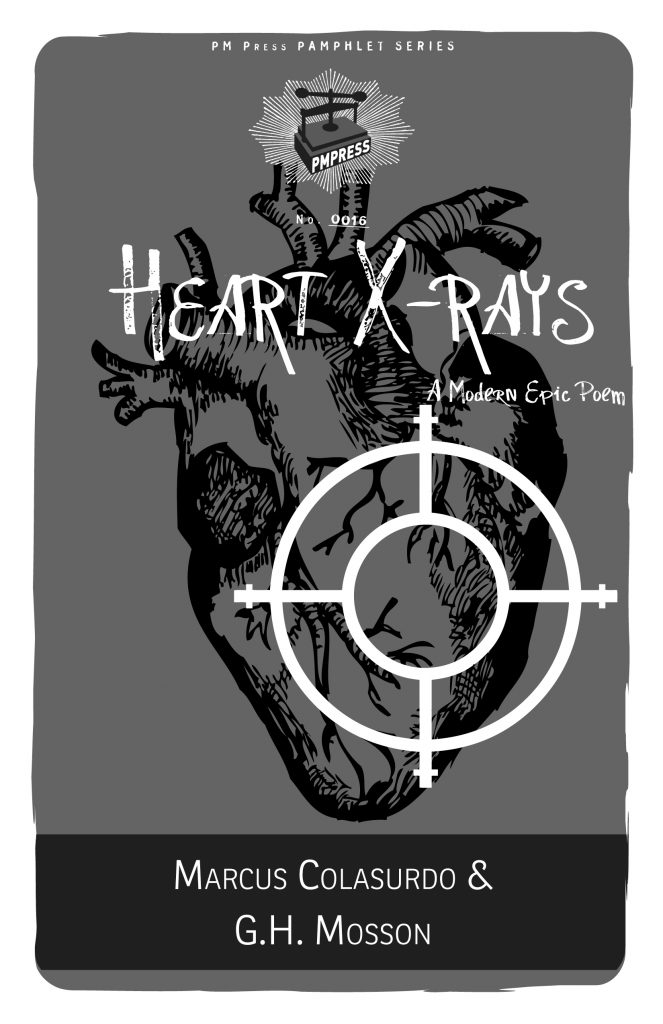

Back to G.H. Mosson’s Author Page | Back to Marcus Colasurdo’s Author Page